Last updated: May 17, 2023

Article

Separate But Equal? South Carolina's Fight Over School Segregation (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

"Immediately cease discriminating against Negro children of public school age in said district and county and immediately make available…educational advantages and facilities equal in all respects to that which is being provided for whites…"

Excerpt from the Petition of Harry Briggs to the Board of Trustees for School District No. 22, 19491

During the era of segregation, South Carolina school districts viewed the education of African American students as unimportant. It was illegal for black and white children to attend school together and the state provided little education for African Americans past the tenth grade.2 In 1951, a lawsuit known as Briggs v. Elliott forced the state to address the disparities and problems in funding public education. As a result, South Carolina passed its first statewide sales tax. The money from the three percent tax was dedicated to building and improving schools across the state for both African American and white students, in both rural and urban regions. It was South Carolina's attempt to build a "separate but equal" school system.3

Over 700 schools were constructed, improved, or expanded under the program. Through the 1950s, sleek, distinctly modern schools of brick, glass block, and walls of windows dotted the state. During that time, Briggs v. Elliott went to the U.S. Supreme Court as one of the five cases decided in Brown v. Board of Education. Today, South Carolina's "equalization schools" are still visible across the state. Their history is often forgotten, but they stand as reminders of America's "separate but equal" school systems.

1 Petition of Harry Briggs, et al., to the Board of Trustees for School District No. 22, Clarendon County Board of Education, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC, 11 November 1949.

2 J.A. DeLaine, Jr. Briggs v. Elliott: Clarendon County's Quest for Equality (Pine Brook, NJ: O. Gona Press, 2002), 3-6.

3 Walter Edgar, South Carolina: A History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), 521-523.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places documentation for "Summerton High School" (with photos), "Florence C. Benson Elementary School" (with photos), "Mary H. Wright Elementary School" (with photos), and the Multiple Property Submission "Equalization Schools of South Carolina, 1951-1960." This lesson was written by Rebekah Dobrasko, historian with the Texas Department of Transportation, previously a historian at the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, and author of SCEqualizationSchools.org. It was edited by Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American History and Social Studies courses in units on the history of education in the United States, African American history, civil rights and law, Southern history, and the 20th Century African American Civil Rights movement.

Time period: Mid-20th century

Relevant United States History

Standards for Grades 5-12

Separate But Equal? South Carolina's Fight Over School Segregation

relates to the following National Standards for History:

-

Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

-

Standard 4A - The student understands the "Second Reconstruction" and its advancement of civil rights

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Separate But Equal? South Carolina's Fight Over School Segregation

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture.

-

Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals' daily lives.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, & Governance

-

Standard H - The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice, and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard E - The student explains and analyzes various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

1)To explain how the policy of "separate but equal" affected education in the middle of the twentieth century;

2)To describe the effects of Briggs v. Elliott on the construction of school buildings in South Carolina and on racial segregation in the United States;

3)To explain some of the ways that individuals and institutions worked to maintain racial segregation in the United States;

4)To compare and contrast equalization schools in South Carolina with their own schools and education system.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) two maps showing population density in South Carolina and the distribution of equalization schools for black and white students in South Carolina;

2) one primary source document of the Briggs v. Elliott equalization petition to the Court;

3) three readings on the events of Briggs v. Elliott, the school equalization program, and the Modern architecture of equalization schools;

4) three historic photos of equalization schools and one contemporary photo of a historic equalization school;

Visiting the site

Summerton High School is located on South Church Street in Summerton, South Carolina. It is still owned by the Clarendon County School District One, and serves as the district's offices. The school is located on South Church Street in Summerton, South Carolina. The school is not open to the public, although it is visible from the public right-of-way. Special tours of the school may be arranged by contacting the Clarendon County School District One's offices at (803) 485-2325 or visiting http://www.clarendon1.k12.sc.us.

The Florence C. Benson Elementary School, located off South Bull Street in Columbia, South Carolina, is currently owned by the University of South Carolina. The university's Center for Developmental Disabilities and the Department of Environmental Health and Safety are located in the school. The school is not open to the public, although it is visible from the public right-of-way. For additional information, please contact the USC Facilities department at (803) 777-3499 or faccomm@fmc.sc.edu.

Mary H. Wright Elementary School is located at 201 Caulder Avenue in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The historic school is adjacent to the new Mary H. Wright Elementary School. The historic school is currently occupied by the City of Spartanburg and houses the offices of the Spartanburg Housing Authority and the City of Spartanburg Planning Department. For more additional information, contact the City Planning Department at (864) 596-2068.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Why do you think South Carolina wanted to build more schools at this time?

Setting the Stage

After slavery was abolished and Reconstruction ended, Southern states began to re-segregate society on the basis of race with new laws. The Supreme Court supported the Southern states' segregation laws in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Southern states quickly segregated all public spaces after the Plessy decision. African Americans never received a "separate but equal" education. Black schools were small and dilapidated. Generally, black teachers were not as well-educated as white teachers. Although programs such as the Rosenwald Fund, Jeanes Teachers, and the General Education Fund gave outside help to Southern schools, school boards continued to ignore black education.1

A survey of South Carolina's schools in the late 1940s showed that the state's school facility investment for white students totaled approximately $221 per pupil. The school plans for African American students reflected an investment of $45 per pupil. One-third of South Carolina's draftees in World War II were rejected by the Army due to illiteracy.2

After World War II, the civil rights movement began to grow and push for African American rights. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) led the legal aspect of the civil rights movement, suing for equal teacher pay, voter rights, and equal educational opportunities. In the late 1940s, the NAACP sued on behalf of African American college and graduate students, winning court decisions requiring equalization or desegregation of white universities.3

1 Walter Edgar, South Carolina: A History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998).

2 Public Schools of South Carolina: A Report of the South Carolina Education Survey Committee (Nashville, TN: Division of Surveys and Field Services, George Peabody College for Teachers, 1948); Dobrasko.

3 Mark Tushnet, The NAACP's Legal Strategy Against Segregated Education, 1925-1950 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 131-136; Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America's Struggle for Equality (New York: Vintage Books, 2004); Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal:' South Carolina's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955," M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 2005.

Locating the Site

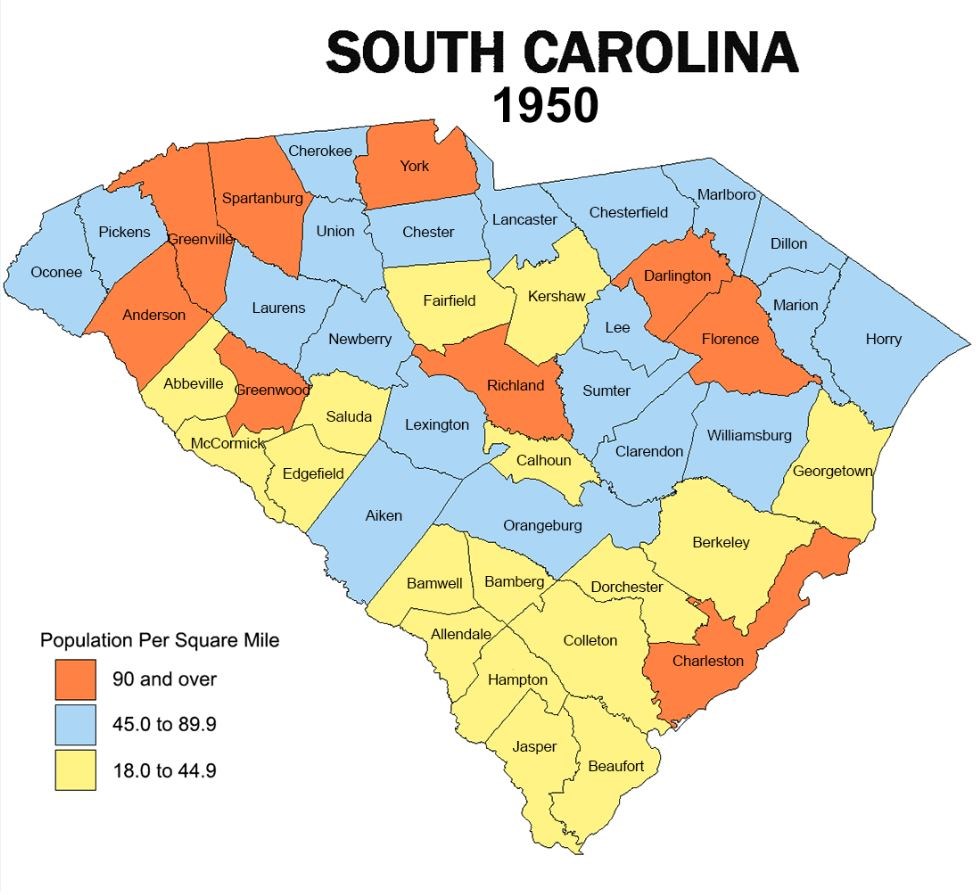

Map 1: Population Density in South Carolina, 1950.

South Carolina's schools were segregated by race in 1950. School districts bought buses for white children to go to their schools but no school district paid for buses to take African American students to school.

"Population density" counts the number of people who live in one square mile of land. Counties with cities have a high population density (about 90 people and over in every square mile) and most people live very close to each other. Rural counties have a low population density (about 18 to 44.9 people) and people live farther apart from each other. Counties with both small towns and rural areas are in the middle. These places have about 45 to 89.9 people living in every square mile of land.

Questions for Map 1

1) Was South Carolina mostly rural or urban in 1950?

2) How far do you think a student might travel to get to school in a Charleston County school district? How far might a student in Hampton County travel? Why do you think so?

3) Find Clarendon County. How dense is its population? Why do you think parents in Clarendon County would want school buses for their children?

4) What effects do you think no funding for school buses had on African American families in South Carolina? Why? How do you think it affected students?

Determining the Facts

Document 1: Briggs v. Elliott Petition, 11 November 1949

This is a legal document that Clarendon County parents signed in 1949 for their children enrolled in segregated African American schools. This document was not filed in court because it was rewritten to call for the desegregation of the schools.

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

PETITION

COUNTY OF CLARENDON

To: The Board of Trustees for School District Number 22, Clarendon County, South Carolina. R.W. Elliott, Chairman, J.D. Carson and George Kennedy, Members; The County Board of Education for Clarendon County, South Carolina, L.B. McCord, Chairman, Superintendent of Education for Clarendon County, A.J. Plowden, W.E. Baker, Members, and H.S. Betchman, Superintendent of School District #22.

Your petitioners, Harry, Eliza, Harry Jr., Thomas Lee, Katherine Briggs, and Thomas Gamble; [Here the petition lists the rest of the names of the parents and their students], children of public school age, eligible for elementary and high school education in the public schools of School District #22, Clarendon County, South Carolina, their parents, guardians and next friends respectfully represent:

1. That they are citizens of the United States and the State of South Carolina and reside in School District #22, in Clarendon County and State of South Carolina.

2. That the individual petitioners are Negro children of public school age who reside in said county and school district and now attend the public schools in School District #22, in Clarendon County, South Carolina, and their parents and guardians.

3. That the public school system in School District 322, Clarendon County, South Carolina, is maintained on a separate, segregated basis, with white children attending the Summerton High School and the Summerton Elementary School, and Negro children forced to attend the Scott's Branch High School, the Liberty Hill Elementary School or Rambay Elementary School solely because of their race and color.

4. That the Scott’s Branch High School is a combination of an elementary and high school, and the Liberty Hill and Rambay Elementary Schools are elementary schools solely.

5. That the facilities, physical condition, sanitation and protection from the elements in the Scott’s Branch High School, the Liberty Hill Elementary School and Rambay Elementary School, the only three schools to which Negro pupils are permitted to attend, are inadequate and unhealthy, the buildings and schools are old and overcrowded and in a dilapidated condition; the facilities, physical condition, sanitation and protection from the elements in the Summerton High in the [sic] Summerton Elementary Schools in school district number twenty-two are modern, safe, sanitary, well equipped, lighted and healthy and the buildings and schools are new, modern, uncrowded and maintained in first class condition.

6. That the said schools attended by Negro pupils have an insufficient number of teachers and insufficient class room space, whereas the white schools have an adequate complement of teachers and adequate class room space for the students.

7. That the said Scott’s Branch High School is wholly deficient and totally lacking in adequate facilities for teaching courses in General Science, Physics, and Chemistry, Industrial Arts and Trades, and has no adequate library and no adequate accommodations for the comfort and convenience of the students.

8. That there is in said elementary and high schools maintained for Negroes no appropriate and necessary central heating system, running water or adequate lights.

9. That the Summerton High School and Summerton Elementary School, maintained for the sole use, comfort and convenience of the white children of said district and county, are modern and accredited schools with central heating, running water, adequate electric lights, library and up to date equipment.

10. That Scott’s Branch High School is without services of a janitor or janitors, while at the same time janitorial services are provided for the high school maintained for white children.

11. That Negro children of public school age are not provided any bus transportation to carry them to and from school while sufficient bus transportation is provided white children traveling to and from schools which are maintained for them.

12. That said schools for Negroes are in an extremely dilapidated condition, without heat of any kind other than old stoves in each room, that said children must provide their own fuel for said stoves in order to have heat in the rooms, and that they are deprived of equal educational advantages with respect to those available to white children of public school age of the same district and county.

13. That the Negro children of public school age in School District #22 and in Clarendon County are being discriminated against solely because of their race and color in violation of their rights to equal protection of the laws provided by the 14th amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

14. That without the immediate and active intervention of this Board of Trustees and County Board of Education, the Negro children of public school age of aforesaid district and county will continue to be deprived of their constitutional rights to equal protection of the laws and to freedom from discrimination because of race or color in the educational facilities and advantages which the said District #22 and Clarendon County are under a duty to afford and make available to children of school age within their jurisdiction.

WHEREFORE, Your petitioners request that: (1) the Board of Trustees of School District Number twenty-two, the County Board of Education of Clarendon County and the Superintendent of School District #22 immediately cease discriminating against Negro children of public school age in said district and county and immediately make available to your petitioners and all other Negro children of public school age similarly situated educational advantages and facilities equal in all respects to that which is being provided for whites; (2) That they be permitted to appear before the Board of Trustees of District #22 and before the County Board of Education of Clarendon, by their attorneys, to present their complaint; (3) Immediate action on this request.

Dated 11 November 1949

[Signatures of petitioners and attorneys follow]

Questions for Document 1

1) What was the purpose of this document? What problems did the petitioners want to confront?

2) How were Clarendon County's white schools different from African American schools?

3) What effects do you think the unequal treatment might have had on an African American student’s education and his or her future?

4) Why do you think the Clarendon County parents decided not to use this petition and instead sue for desegregation?

Document 1 is excerpted from the transcription of the Petition of Harry Briggs, et al., to the Board of Trustees for School District No. 22, Clarendon County Board of Education, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC, 11 November 1949.

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: From Briggs v. Elliott to Brown v. Board of Education

The state constitution that South Carolina adopted in 1895 mandated racial segregation in public schools. In 1896, the Supreme Court of the United States decided that it was constitutional to separate black and white Americans in public places. This decision was the result of the Plessy v. Ferguson case. The court's idea was that racial segregation worked with American ideals as long as everyone received the same kinds of public services. This meant that if a water fountain in a courthouse was 'whites only,' then the local government had to provide a water fountain for Americans who were not white, too. This also meant that if a state or a local school board built a school for white children, they were bound by the U.S. Constitution to build a school for black children. This racist policy is called "separate but equal." It protected and supported racial segregation in the United States for over 50 years.

South Carolina used this policy in its public school system. However, while schools were separate, South Carolina never made sure they were equal. In the late 1940s, South Carolina spent $221 per white student versus $45 per black student in its schools.1 Outside of South Carolina's cities and towns, many African American students had to walk ten miles or more to get to school.2

African American parents in South Carolina wanted their children to have the same services and schools with the same quality as the white children. In Clarendon County, a rural county in South Carolina, Reverend Joseph A. DeLaine led the parents' efforts to make this happen. DeLaine was a local pastor and teacher at Liberty Hill Elementary School. He worked with local parents and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1947, DeLaine and the parents group sued Clarendon County School District #22 and asked for a bus for black students. The court dismissed the case based on a technicality, but the parents did not give up.3

DeLaine and the local parents decided to sue again. This time they sued in a federal court, not a state court. The lawsuit they filed is called Briggs vs. Elliott. Briggs was the last name of several of the African American children named in the lawsuit. Elliott was the last name of the chairman of the Clarendon County School Board #22 Board of Trustees. This 1949 lawsuit listed the differences between the white Summerton Graded School and the black Scott's Branch School. For example, the Scott's Branch school had outdoor toilets, wells for drawing water, old books, and stoves for heating. Summerton Graded had smaller class sizes, indoor plumbing, and new textbooks. This case was heard by the U.S. District Court in Charleston, South Carolina. The District Court had three judges. One of the judges was Judge J. Waites Waring. Judge Waring, a white man, supported the civil rights movement. He told the NAACP to sue for school desegregation instead of for "separate but equal" schools. Because of this, South Carolina's Briggs v. Elliot became one of the first desegregation cases in the United States.4

South Carolina's new governor, James Byrnes, responded to the lawsuit with a statewide school construction program. The purpose of the program was to "equalize" black and white schools. This plan was in place by the time Briggs v. Elliott went to trial in late May 1951. During the trial, South Carolina's defense argued that it was already trying to provide "separate but equal" schools.5 The U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Clarendon County school district. However, the courts stated that South Carolina should be allowed time to equalize its schools. South Carolina was to give a progress report in six months. Judge Waring disagreed with the court's opinion. He wrote his own opinion to support the NAACP and criticize segregation:

[S]segregation in education can never produce equality and that it is an evil that must be eradicated... the system of segregation in education adopted and practiced in the State of South Carolina must go and must go now. Segregation is per se inequality.6

"Per se" is a legal term, which means "in itself." Judge Waring was stating that he believed segregation can never be "separate but equal." It did not belong in a fair and just society. This was the first time since 1896 that a federal judge disagreed with the "separate but equal" policy.

The NAACP and the Clarendon County parents appealed the District Court's ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court heard Briggs as well as four other cases from Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. These combined cases formed the landmark case known as Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the NAACP, stating that: "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."7 The Supreme Court used Judge Waring's dissent in Briggs v. Elliott when writing these words. Brown v. Board of Education overturned almost 60 years of legal segregation. This case was a victory for African Americans and the Civil Rights Movement.

Although South Carolina lost its case in Briggs v. Elliott, nothing changed immediately in the state. The Clarendon County parents who signed the lawsuit lost their jobs, homes, and land. Rev. DeLaine and his family left the state under a threat of violence. The African American students did receive new equalization schools, but remained segregated until 1963.8

Questions for Reading 1

1) Describe the "separate but equal" policy in your own words. When did it officially become the constitutional policy in the United States? When did it end?

2) Who originally sued the Clarendon County School District #22? What did they want in their petition? How did their goals change in the Briggs v. Elliot lawsuit?

3) Why do you think parents worked so hard to fight segregation in schools, rather than segregation elsewhere (such as in restaurants or in public transportation)?

4) How did the Briggs v. Elliot lawsuit help end racial segregation in the United States?

5) How do you think "separate but equal" segregation is at odds with the stated ideals of the United States?

Reading 1 was adapted from J. Tracy Power and Andrew Chandler, "Summerton High School" (Clarendon County), National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1994, and Racial Segregation in Public Education in the United States Theme Study, National Historic Landmarks Survey, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2000.

1 Public Schools of South Carolina: A Report of the South Carolina Education Survey Committee (Nashville, TN: Division of Surveys and Field Services, George Peabody College for Teachers, 1948), 192-208.

2 J.A. DeLaine, Jr. Briggs v. Elliott: Clarendon County's Quest for Equality (Pine Brook, NJ: O. Gona Press, 2002), 4-7.

3 Julie Magruder Lochbaum, "The Word Made Flesh: The Desegregation Leadership of the Rev. J.A. Delaine," (PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 1993), 61-62.

4 James Clyburn and Jennifer Revels, Uncommon Courage: The Story of Briggs v. Elliott, South Carolina's Unsung Civil Rights Battle (Columbia, SC: Palmetto Conservation Foundation Press, 2004), 30-33.

5 Clyburn and Revels, 33; Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal:' South Carolina's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955" (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 2005), 10-12.

6 "Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr. et al. v. R.W. Elliott, Chairman, et al., Records of the United States District Court, Eastern District of South Carolina, National Archives and Records Administration, 21 June 1951 (available online).

7 Clyburn and Revels, 39; DeLaine, 22.

8 Clyburn and Revels, 36-38; Edgar, 126-127.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: South Carolina's School Equalization Program

One major result of the Clarendon County petitions was that South Carolina decided to build new schools across the state. The new governor of South Carolina, James Byrnes, began his duties in 1951 and he knew that the NAACP could prove that black and white schools were not equal in South Carolina. So, Byrnes developed a program to build new schools for both white and African American children. The new schools were called "equalization schools" because the state built them to comply with the "separate but equal" policy.1

The State Educational Finance Commission (EFC) was in charge of the school building and improving program. The commission purchased new school buses to bring both black and white students to school. The program designed modern buildings for African American students with the same features that white schools usually had, like running water and electricity. School districts closed old one- or two-teacher schools and built larger schools with more teachers and classrooms. South Carolina created its first sales tax to fund the program.

The commission first funded new schools in Clarendon County School District #22, where the Briggs v. Elliott case began. Governor Byrnes used this program to prove that South Carolina was committed to providing "separate but equal" schools. The equalization program was used in arguments for the Briggs v. Elliott lawsuit to defend the school district and the state against the parents. Clarendon County asked the court for more time to build new black schools.

Not all school districts wanted to participate in the program. Many districts wanted to take the funds from the state and only improve their white schools. Charleston County school officials did not want to build a new black high school to replace one that had closed. Some local districts refused to apply for state funds at all if it meant equalizing their schools. When districts combined smaller schools into one large school, many African Americans lost the center of their community. A few black leaders also opposed the new schools, because they wanted desegregation instead of equalization.2

The EFC granted most of its equalization money by 1955. South Carolina built over 700 new schools and spent over $214 million. A newspaper article described the equalization schools as "clean-cut functional buildings, making little or no distinction in design between white and colored schools."3 Even though African American students had new schools, they still lacked books for their libraries and new desks in their classrooms. When the Supreme Court ruled against segregation, South Carolina did not comply.

South Carolina maintained its fully segregated system until 1963. Eleven African American students attended Charleston's white schools under a court order that year, but most school districts were still segregated. The federal government stopped this system by 1970. It refused to give money to segregated school districts. Many of the equalization schools closed at that time. African American high schools often became elementary schools in the new system. Most of the equalization schools have been expanded or replaced with new schools. Some schools are used for a different purpose.4

Questions for Reading 2

1) What were "equalization schools?" How were they named?

2) Who supported the equalization school program? What were their goals?

3) What do you think African American parents thought of the equalization schools program? Why? (Refer to Document 1 if necessary)

4) Why do you think it took 16 years after Brown v. Board of Education for most South Carolina school districts to close their segregated schools?

Reading 2 was compiled from Rebekah Dobrasko, "Architectural Survey of Charleston County's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955," (Columbia: South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, 2005); Rebekah Dobrasko, "Equalization Schools in South Carolina, 1951-1960," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009; Rebekah Dobrasko and Louis Venters, "Florence C. Benson Elementary School" (Richland County, South Carolina), National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009; and Eric Plaag, "Mary H. Wright Elementary School," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009.

1 Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal:' South Carolina's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955 (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 2005).

2 "The Byrnes Tax," Lighthouse and Informer (Columbia, SC), 7 July 1951; Dobrasko, 16-17.

3 Thomas D. Clark, "The Modern South in a Changing America," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 107, no. 2 (15 April 1963): 129.

4 Dobrasko, 36-37. For an partial list of all the schools built under the equalization program, see www.scequalizationschools.org.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: South Carolina's School Equalization Program

One major result of the Clarendon County petitions was that South Carolina decided to build new schools across the state. The new governor of South Carolina, James Byrnes, began his duties in 1951 and he knew that the NAACP could prove that black and white schools were not equal in South Carolina. So, Byrnes developed a program to build new schools for both white and African American children. The new schools were called "equalization schools" because the state built them to comply with the "separate but equal" policy.1

The State Educational Finance Commission (EFC) was in charge of the school building and improving program. The commission purchased new school buses to bring both black and white students to school. The program designed modern buildings for African American students with the same features that white schools usually had, like running water and electricity. School districts closed old one- or two-teacher schools and built larger schools with more teachers and classrooms. South Carolina created its first sales tax to fund the program.

The commission first funded new schools in Clarendon County School District #22, where the Briggs v. Elliott case began. Governor Byrnes used this program to prove that South Carolina was committed to providing "separate but equal" schools. The equalization program was used in arguments for the Briggs v. Elliott lawsuit to defend the school district and the state against the parents. Clarendon County asked the court for more time to build new black schools.

Not all school districts wanted to participate in the program. Many districts wanted to take the funds from the state and only improve their white schools. Charleston County school officials did not want to build a new black high school to replace one that had closed. Some local districts refused to apply for state funds at all if it meant equalizing their schools. When districts combined smaller schools into one large school, many African Americans lost the center of their community. A few black leaders also opposed the new schools, because they wanted desegregation instead of equalization.2

The EFC granted most of its equalization money by 1955. South Carolina built over 700 new schools and spent over $214 million. A newspaper article described the equalization schools as "clean-cut functional buildings, making little or no distinction in design between white and colored schools."3 Even though African American students had new schools, they still lacked books for their libraries and new desks in their classrooms. When the Supreme Court ruled against segregation, South Carolina did not comply.

South Carolina maintained its fully segregated system until 1963. Eleven African American students attended Charleston's white schools under a court order that year, but most school districts were still segregated. The federal government stopped this system by 1970. It refused to give money to segregated school districts. Many of the equalization schools closed at that time. African American high schools often became elementary schools in the new system. Most of the equalization schools have been expanded or replaced with new schools. Some schools are used for a different purpose.4

Questions for Reading 2

1) What were "equalization schools?" How were they named?

2) Who supported the equalization school program? What were their goals?

3) What do you think African American parents thought of the equalization schools program? Why? (Refer to Document 1 if necessary)

4) Why do you think it took 16 years after Brown v. Board of Education for most South Carolina school districts to close their segregated schools?

Reading 2 was compiled from Rebekah Dobrasko, "Architectural Survey of Charleston County's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955," (Columbia: South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, 2005); Rebekah Dobrasko, "Equalization Schools in South Carolina, 1951-1960," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009; Rebekah Dobrasko and Louis Venters, "Florence C. Benson Elementary School" (Richland County, South Carolina), National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009; and Eric Plaag, "Mary H. Wright Elementary School," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009.

1 Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal:' South Carolina's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955 (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 2005).

2 "The Byrnes Tax," Lighthouse and Informer (Columbia, SC), 7 July 1951; Dobrasko, 16-17.

3 Thomas D. Clark, "The Modern South in a Changing America," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 107, no. 2 (15 April 1963): 129.

4 Dobrasko, 36-37. For an partial list of all the schools built under the equalization program, see www.scequalizationschools.org.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: New Architecture For New Schools.

Americans did not build many schools during World War II. There was not a lot of money to buy school supplies and building materials. Steel, concrete, and lumber were used to support the war. After the war, these materials were available again. Also, more Americans married and had children after the war. More schools had to be built in the 1940s and 1950s because of the "baby boom." Local governments were able to build these schools because there was tax money available to buy building materials and workers available to build them.

Just before the era of the baby boom, school buildings began to copy the new "modern" form of architecture. Before then, schools were usually built out of wood or brick. Many were multi-story. Older schools in rural areas were single story and had only one or two rooms. New schools were usually one-story buildings. Architects used concrete block to construct schools and classrooms in the modern style. The concrete frames of the new schools were covered with brick to improve the look of the school. Older schools had wood frames and sloping roofs. Modern schools had steel beam frames and flat roofs.

The new one-story schools did not need staircases and fire escapes. Classrooms located on one floor provided easy access to the outdoors. Many schools had classrooms that opened directly to the outside instead of a hallway. Architects chose this design because it improved ventilation (air flow) and natural lighting in the classrooms. Lighting and ventilation in older schools was poor. New classrooms had nine-foot ceilings and "window-walls." Rows of windows across the facade (the outside of a building) allowed an abundance of light to enter the classroom. Architects used modern-style materials like glass blocks that softened the light in the classroom.

The inside of modern schools did not look like the old ones. Teaching styles changed and the new schools adapted to the new styles. The desks and chairs in older schools were nailed to the floor. This limited the ways that students and teachers could use the classroom. Teachers and students could move their tables, chairs, and desks around the room in modern schools.

South Carolina's schools constructed under the equalization program followed modern architectural trends. The equalization schools are very distinctive in their design and construction. The State Educational Finance Commission required all new schools to be designed by a licensed architect. Architects designed schools with modern materials that reflected the architecture of schools across the nation. Both black and white schools built under this program were similar in design and materials.1

One of the first equalization schools built for African American students was the historic Mary H. Wright Elementary School in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The Spartanburg school board used money from the State Educational Finance Commission to fund the construction. Wright Elementary was one of the first equalization schools in South Carolina.

When it opened in 1951, the Mary H. Wright Elementary school's classrooms had bookshelves, windows, sinks, closets, and chalkboards. Some even had their own toilet. The school had a library, nurse's room, cafeteria, kitchen, and indoor bathrooms. Central boilers, not stoves, heated the school. The school's walls were built from painted concrete blocks. South Carolina's politicians built the Wright School to keep segregation alive. It is also an important historic place because it is an example of how school architecture changed after World War II.

Questions for Reading 3

1) Why were schools not built during World War II? What are some of the reasons that schools were built in the 1950s?

2) What are some of the identifying features of "modern" schools built in the middle of the 20th century? How were they different from older schools?

3) How do you think the "modern" features improved learning?

4) If you were an African American parent in South Carolina, would you be satisfied with sending your children to an equalization school? Why or why not?

Reading 3 was compiled from Rebekah Dobrasko, "Equalization Schools in South Carolina, 1951-1960," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009; and "Mary H. Wright Elementary School," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2009.

1 Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal,'" 22-29; Bryan Collier, "Charleston County's New School Plans are Simple, Inexpensive, and Effective," News and Courier, 21 October 1951.

Visual Evidence

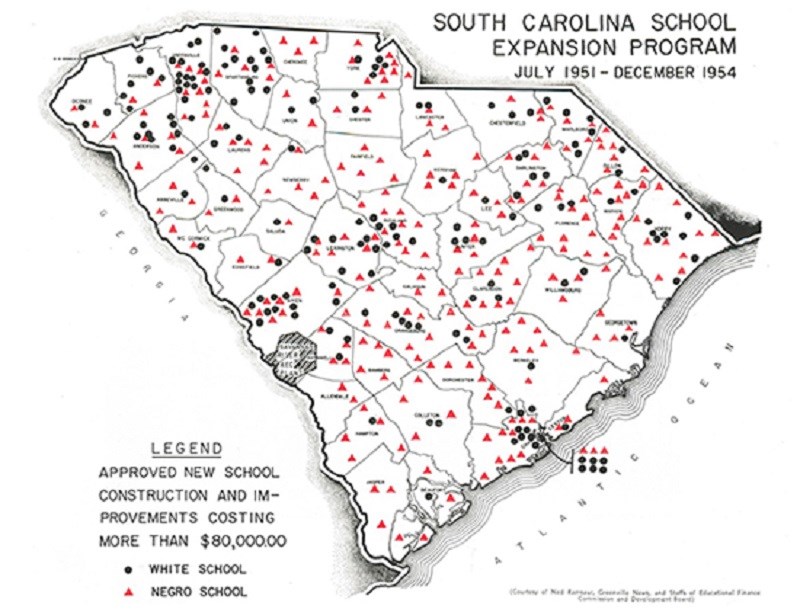

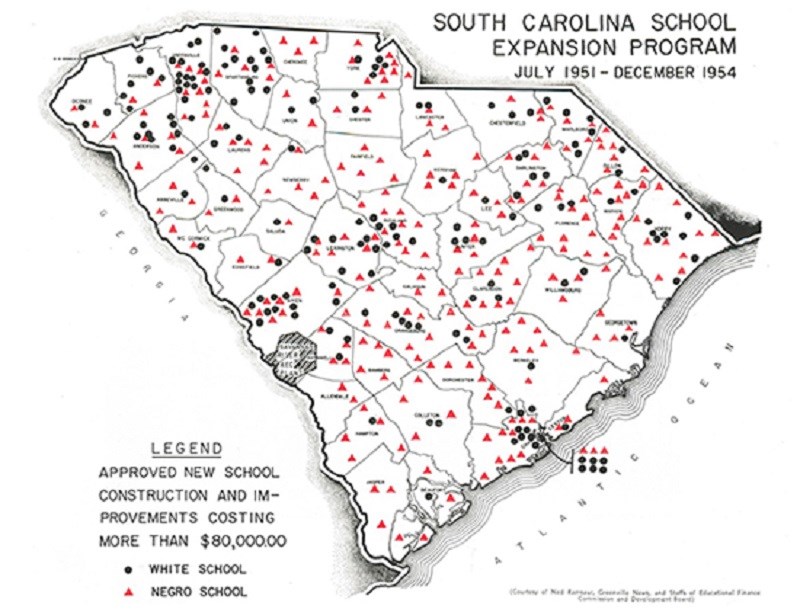

Map 2: Educational Finance Commission New Schools Map.

The State Educational Finance Commission published a report on the equalization program in 1955. This report is titled. "South Carolina's Educational Revolution: A Report of Progress in South Carolina." The report highlighted the new schools constructed, the new buses purchased, and the locations of new schools across the state.

Questions for Map 2

1) Which county had the most new school construction? Which county had the least? (Refer to Map 1 to find the county names)

2) What population patterns do you see in this map? What could these patterns tell you about the need for new African American schools?

3) Find Richland County on the map. How many new schools did Richland County have? Compare Richland County to the surrounding counties. What is the same? What is different?

4) This map was part of a report labeled "Progress in South Carolina." Do you think this map shows progress in education? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Scott's Branch High School, Clarendon County, c. 1952.

The first equalization school in South Carolina opened at Scott's Branch High School outside of Summerton in Clarendon County. The school district built this new school in response to the Briggs v. Elliott lawsuit.

Questions for Photo 1

1) Why are these two different school buildings adjacent to one another?

2) Which school building is the newer one? Why do you think so?

3) Do you think that the new school building was a good replacement for the old Scott's Branch school? Why or why not?

4) Which building would you rather attend for school? Why?

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Jane Edwards Elementary School, Charleston County, 1955.

(Photograph courtesy of the Charleston County School District, Archives Department)

Questions for Photo 2

1) When do you think this building was built? Why do you think so?

2) What would you expect to see at an elementary school that is not shown in this photograph? Why do you think that is?

3) In what ways is this building similar to your school? How is it different? What do you think explains the similarities and differences?

Visual Evidence

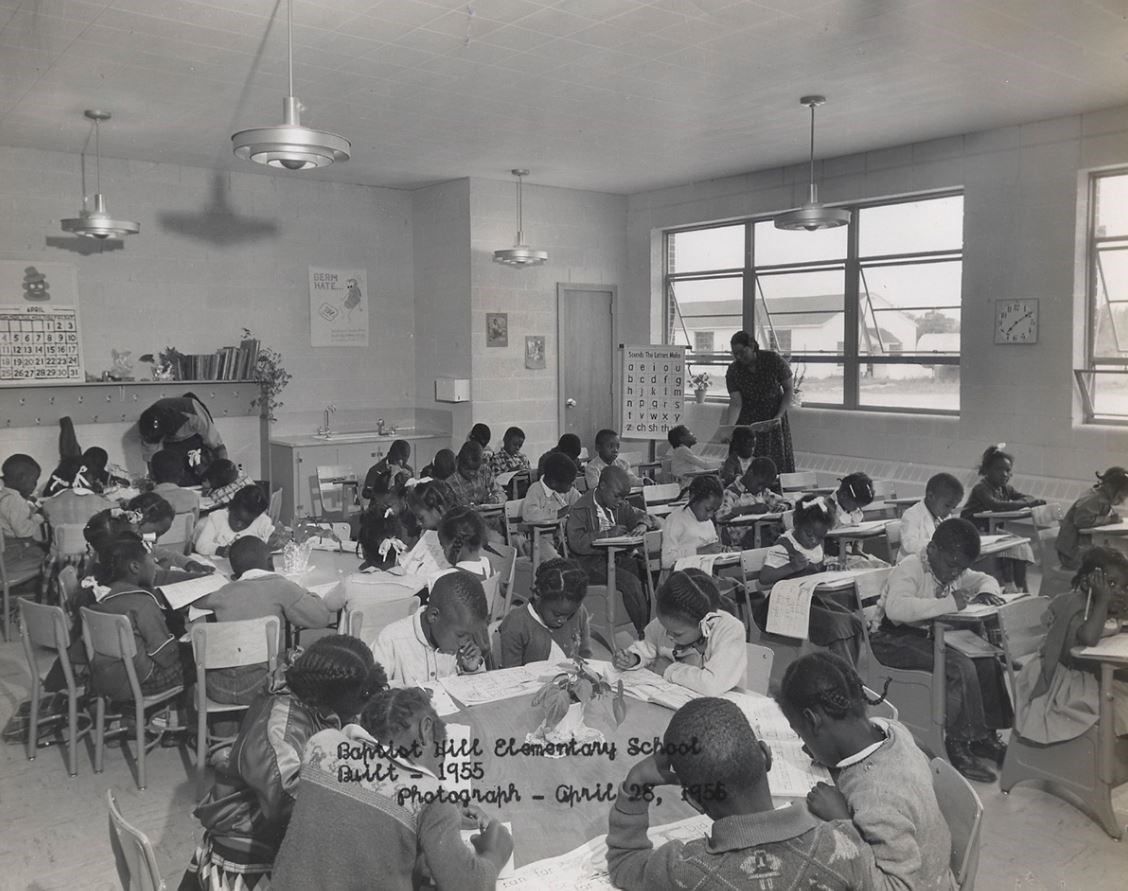

Photo 3: Baptist Hill Elementary School, Charleston County, 1956.

Questions for Photo 3

1) Describe the features of the room. Where do heat, light, and water come from? What kinds of furniture and learning materials do you see?

2) Is this an "equalization school?" Why do you think so? (Refer to Reading 4, if necessary)

3) How is your school similar to an equalization school? In what ways is it different? Does your classroom look like the one in Photo 3? Explain.

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Florence C. Benson Elementary School, Richland County, 2009.

(Photograph by Rebekah Dobrasko)

Florence C. Benson Elementary School opened in 1954. African American students in Columbia, South Carolina, attended Benson. The school had classrooms, a library, and a cafeteria/auditorium. In 1954, there were 270 students in the first through sixth grades.

Questions for Photo 4

1) How is this building "modern"? What evidence can you see in the photo that this is an equalization school?

2) How many rooms do you think are in this school? (Hint: see how many you think there are on the second level and multiply by 3.) Using the number of classrooms, calculate how many students there were in each class.

3) How is this school and its surroundings similar to the schools in Photos 1 and 2? How is it different? Why do you think this is? (Refer to Map 1 if necessary)

Putting It All Together

The following activities will guide students to use what they have learned about desegregation and equalization schools in South Carolina to understand how massive resistence, educational inequality in opportunity, and desegregation can be national or even global themes.

Activity 1: Massive Resistance in the South

Have students study the ways Americans in southern states resisted federal laws, rulings, and mandates that were aimed at ending segregation. During the 1950s and 1960s, many white Americans tried to prevent desegregation. The organized, negative response by these people to the African American civil rights movement was called "Massive Resistance" following the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The equalization schools program is one of the early examples of resistance to desegregation in that era.

Assign groups of students one of the following states and have the groups prepare a group PowerPoint presentation or simple oral presentation by researching segregation laws and court decisions related to segregation in their state: Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, or Maryland. All of these states plus South Carolina mandated school segregation in 1950.

Each group's presentation in front of the class should address the following questions about their state: What were the laws mandating segregation in that state in 1954? How did these laws affect the people living there? In what ways did white Americans in that state try to preserve these laws and how successful were they? What individuals or organizations led the Massive Resistance movements in those states? What individuals or organizations stood up to Massive Resistance? How was Massive Resistance in this state similar to white resistance to school desegregation in South Carolina? If it was different, how was it different?

An alternate option for this activity is to have your students work independently and write a research paper about Massive Resistance. They should answer and provide examples for the same questions about a state with segregation laws in 1954.

Activity 2: Desegregating the U.S.: The Lawsuits of Brown v. Board of Education

Briggs v. Elliott was one of five lawsuits combined in the Brown v. Board Supreme Court ruling or 1954. Have your students study the lawsuits to create a poster series about them:

-

Belton v. Gebhart (Bulah v. Gebhart) in Delaware

-

Brown v. Board of Education in Kansas

-

Briggs v. Elliott in South Carolina

-

Bolling v. Sharp in Washington, D.C.

-

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County in Virginia

Divide the class into five groups and assign each group one of the lawsuits. Have each group research and design a poster presentation about the schools that were part of the lawsuits, the laws in those states related to school desegregation, who was suing whom and why in those cases, and what happened in those school districts after the ruling in 1954. Have your students include images and quotes to illustrate the history of those cases on their posters. Display your students' posters in the school hallway or your own classroom.

After your students complete their poster exhibit, invite someone who remembers segregation to your classroom to talk about desegregation and their memories of it during the 1950s/1960s. For a balanced perspective, consider inviting both a white and an African American speaker. Allow your students to ask questions and finish the activity with a class discussion. What did the students find surprising about the speaker's experiences? What were they not surprised to hear? Did the speaker's memories confirm or contrast with what they learned already?

Activity 3: Extra! Extra! Unequal Education in the United States!

In this activity, take on the role of news editor and turn your students into journalists reporting on the history of inequalities in American education. Assign each of your students a group that has been barred by law or by circumstance from the best education or extracurricular opportunities available in their community. This includes girls, religious minorities, young immigrants and the children of immigrants, child laborers, or children with learning or physical disabilities.

Ask your students to imagine they are newspaper reporters living at the time of an important milestone in education rights for their assigned disadvantaged group. Have them each research their group, identify a milestone, and then write an article that explains the challenges the group faces, who champions for it, what happened in the milestone event, and what challenges remain. Have your students include quotes from primary source documents related to the lawsuit or the issue, and identify an image from the era to illustrate their article. They should also include a historical date on their news article.

Compile your students' articles with a word processor and print them out to display their work as broadsides of a newspaper. If you wish to incorporate technology, have your students publish their articles and historical images together in a class blog.

Activity 4: Map Your Community's School History

Engage your students with their community's history to show them how the national events and regional history they learn about in their curriculum relates to their own experience. In this activity, have your students create a class timeline and tour of historic and current schools in your county with an online map builder (Google Earth Tour Builder) to learn more about changes in education and racial policies in the twentieth century.

Students can work in small groups at first to gather information for the class project:

-

The name of the school and whether it was a segregated "white school" or a "black school"

-

Year it was built and a description of its architecture

-

Month and year it desegregated, if it desegregated

-

Reason it desegregated (court case, school district plan, etc.) or reason why it was never segregated to begin with.

-

Any changes made to the school after desegregation (i.e. new mascot? New school colors? High school to elementary school?)

-

Current or historic photograph of the school (if available)

Some school buildings from the early twentieth century might be used for other purposes now or have been demolished. After each group completes their investigation, the class will use the information to create their online tour.

Ask your students if what they learned about their community's schools surprised them. What were the district schools like in the early part of the century? Did the schools change in the middle of the twentieth century? How did they change? If you live in another state, wrap up the activity by asking the students to compare and contrast their school district's history with the history of districts in South Carolina.

Separate But Equal? South Carolina's Fight Over School Segregation--

Supplementary Resources

After completing Separate but Equal? South Carolina's Fight over School Segregation, students have studied the ways that the mid-twentieth century fight over segregation, the rise of modern architecture, and the undeniable inequality in education led to the construction of South Carolina's distinct equalization schools in the 1950s. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of materials.

South Carolina's Equalization Schools

This dedicated online resource about the South Carolina equalization school program provides a brief history of the equalization school program, historic and current photographs of equalization schools, and an ongoing list of identified equalization schools across the state. The website is maintained by this lesson plan's author, historian Rebekah Dobrasko.

Equalization Schools on Flickr

The Equalization School Flickr page features over 1,000 photographs of equalization schools that still exist today. The page has a variety of photographs showing the schools' interiors and exteriors as they look in the 21st century, as well as some historic photographs of schools.

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian exhibit, "Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education", provides context for the five court cases that comprised the Brown decision. The online component of the exhibit showcases photographs of historic schools, detailed information on the history of each case and the individuals involved in each case, and other teacher resources.

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives maintains the Documents Related to Brown v. Board of Education website, which provides the full dissent to the first Briggs v. Elliott case written by Judge Waties Waring in 1951 as well as other public documents related to the Brown v. Board cases.

SCIway, South Carolina's Information Highway

SCIway is a clearinghouse for information about South Carolina. SCIway has collected information on African American schools in South Carolina, including links to historic photographs and websites with more information.

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site

This National Park Service unit is located at Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Monroe was the segregated school attended by the lead plaintiff's daughter, Linda Brown, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in 1951. The park website provides in-depth information on the Brown v. Board case as well as related cases, as well as information for visitors and researchers.

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

The Judicial System

The Judicial SystemHow does the judicial system work? What is a federal court? Why are people trying to reclassify certain offenses?

-

Federalism

FederalismWhat is federalism? How have some Americans used debates about federalism to promote segregation?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

Tags

- african american history

- education history

- south carolina

- south carolina history

- african american education

- segregated schools

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- desegregation

- desegregation of public education

- civics

- civil rights

- art and education

- shaping the political landscape

- late 20th century

- education

- african american sites

- early 20th century

- early 20th century history

- progressive era

- gilded age

- mid 20th century

- twhplp

- wwii aah

- crbp aah