Part of a series of articles titled Claiming Civil Rights .

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Capturing the Nation’s Attention, the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights March

This lesson plan was adapted by Katie McCarthy from the full-length Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan “The Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights March: Shaking the Conscience of the Nation.”

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Students will be able to...

-

Describe the events that occurred during the course of the marches of March 7 and March 21-25, 1965.

-

Analyze the roles played by local activists and national organizations in the voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama.

-

Cite specific textual evidence to support their analysis of a secondary and primary source.

-

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view.

Inquiry Question:

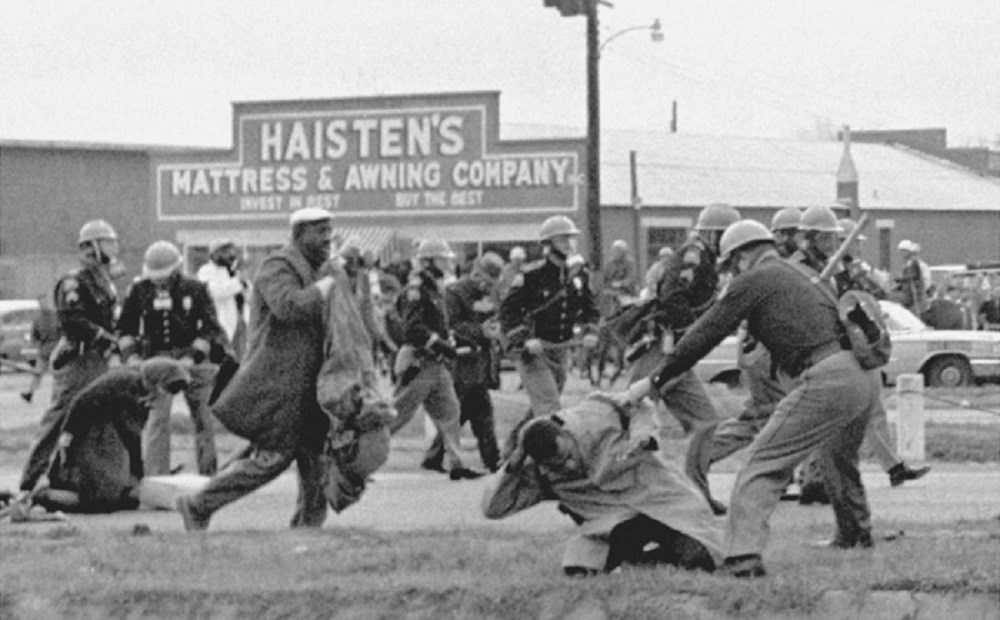

What is happening in this photo? What do you see that makes you think that? What do you still need to figure out?

Reading:

Background:

By 1965, African Americans in the United States had possessed the right to vote for almost a hundred years. However, Black citizens attempting to vote encountered often insurmountable barriers. These included poll taxes, literacy tests, rules that limited voting to people whose ancestors had voted in the past, and party primary elections that were limited to whites.

Civil rights workers had long recognized that the right to vote was central to achieving full citizenship. In the 1950s and 1960s, many civil rights organizations turned to mass demonstrations and nonviolent acts of civil disobedience. Martin Luther King, Jr. became internationally known for promoting, supporting, and participating in nonviolent disobedience.

Peaceful demonstrations attracted media coverage, particularly when they were met with violent opposition. Media helped generate the outrage and widespread support needed for the passage of civil rights legislation. This legislation sought to achieve equal education, access to places of public accommodation and transportation, and equal employment. Despite previous legislation, by 1965 most Southern Black men and women were still blocked from voting.

Millions of people all over the United States were watching television on Sunday night, March 7, 1965. Their programs were interrupted with shocking images of African-American men and women being beaten with billy clubs in a cloud of tear gas. They were attempting to march peacefully from the small town of Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, the state capital. The marchers were protesting a brutal murder and the denial of their constitutional right to vote. Instead, six hundred people were attacked by state troopers and mounted deputies dressed in full riot gear. Most viewers had never heard of Selma, but after March 7, they would never forget it.

Eight days after “Bloody Sunday,” President Lyndon Johnson made a famous and powerful speech to a joint session of Congress. In it, he introduced voting rights legislation. He called the events in Selma “a turning point in man's unending search for freedom." He compared the march to the Revolutionary War battles of Concord and Lexington. On March 21, more than one thousand people left Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma and set out for Montgomery. This time they were watched over by regular Army and Alabama National Guard units ordered by President Johnson to protect the marchers against further violence. At the successful completion of the march on March 25, Martin Luther King, Jr., addressed a crowd estimated at 25,000 in front of the Alabama State Capitol. He quoted the Battle Hymn of the Republic: “His truth is marching on.”1 Five months later, on August 6, 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act is “generally considered the most successful piece of civil rights legislation ever adopted by the United States Congress.” 2

Content:

Marie Foster (Selma resident, active in the Dallas County Voters League): I called Amelia Boynton [and] we met the 23rd day of January, 1963. I said, "Well how about this, let's start a citizenship class." I said, "And we publish it, we advertise through the churches and by telephone and just personal contact, and just beg people to please come to the class, that we're going to make sure that they'll be able to fill out the applications correctly." Well anyway, one person came with all that publication. That Thursday night, the same person came back and brought a relative, and that was two people, and then so on. And I was very successful with that citizenship class.

John Lewis (head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1965): So Dr. King received the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1964, and right after returning from Europe he, in a conversation with President Johnson, he said, "We need a Voting Rights Act. We need a strong Voting Rights Act." And President Johnson and people in the administration said in effect Dr. King, you know, we just signed the Civil Rights Act of '64 and it's just going to be impossible to get another. And so Dr. King said to us, "Well we will write that act. We will write that act."

C. T. Vivian (National Director of Affiliates for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1965): So the thing is, you've got to make the nation understand what's happening, which means that you've got to have the press. We made national television and national television made us. You see what I mean? We made national television news something that people wanted to see every day. Television was made for us, because we're action-oriented. We didn't become action-oriented for the sake of the TV, we became action-oriented because that's nonviolent direct action.

John Lewis: as an individual and as chairman of SNCC I took the position that we should march from Selma to Montgomery [in March 1965]. We had to somehow take the message to Governor Wallace, that we had to have a showdown in Alabama. The Executive Committee of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [as a whole] opposed the idea of the march, but said, well, you can march as an individual but not as chairman of SNCC.

Jamie Wallace (reporter for the Selma Times Journal in 1965): It was obvious to those of us in the media that this was to be a symbolic gesture. It was not a serious march to Montgomery. Ladies had on high-heel shoes, the absence of Dr. King and the national media and so forth. So we felt like it was strictly a symbolic gesture to cross a bridge, go to a point about 100 yards beyond the bridge and probably turn around and come back, and be able to say that we did it even though they told us not to do it.

Amelia Boynton (Selma Resident, widow of Samuel Boynton and active in the Dallas County Voters Leagues in 1965): So that Sunday morning I went immediately to the church. I had on high-heel shoes, because at that time I didn't wear low-heel shoes. I started out with the rest. Marie Foster and I were in the front. And just before we got to the light across the [Edmund Pettus] bridge, we saw that the road was blocked. I didn't think anything was going to happen, but as we approached, it was announced, "Don't go any farther." And when Hosea Williams said, "May I say something?" Clark said, "No, you may not say anything. Charge on them, men!” And they started beating us. They had horses. And I saw them when they were beating people down, and I just stood. Then one guy hit me with the nightstick, I think it was a nightstick. He hit me with the nightstick just back of the head and down toward the shoulder. And I still stood up there. Then the second lick was at the base of the neck. And I fell. I think that was the ambulance that came from Anderson Funeral Home that took me to the church and tried to revive me but could not revive me. So they took me to the Good Samaritan Hospital. And when I was revived, I really didn't know where I was, but I was there several hours before I really came to.

John Lewis: All over the United States, the people saw what happened on television, they read about it in the newspaper, and there was demonstration after in Washington, every major city in America, and some of our embassies abroad. And Dr. King issued a call, issued an appeal for the religious leaders of America to come to Selma.

Hosea Williams: We were mobilizing fast—we had had marches before but never a march of that magnitude. We began organizing staff plus volunteer supporters in the various departments: food, medical department, program, mobilization, legal redress (had more lawyers than we ever needed), housing (these huge tents), transportation (taking people back to Montgomery or back to Selma), celebrity, communication department. We had it planned out, we knew exactly what time we'd leave that morning, we knew exactly where we'd stop for the ten o'clock break, we knew exactly where we'd stop for lunch, we knew exactly where we'd stop in the afternoon and what time.

John Lewis: I think the day we left Selma [for the second march] was on a Sunday afternoon, March 21st. It was like the beginning of a holy crusade. You know, President Johnson called out the military to protect the marchers along the way, and as we walked that next day, you saw the men of the Army, in their fatigues, guarding the way with their guns drawn. They stayed with us all the way from Selma [to Montgomery].

C. T. Vivian: I join everybody as we go across the bridge. By the time I get to the top of the bridge where you can see everything, that long line, so wide and big and beautiful. It's way, way, way down there. And you could see it, and boy it was beautiful. I mean it's—hey, it's one of the most—just festive, joyful, celebration, to use the great religious term. It was celebration. And a great time.

Hosea Williams (National Director of Voter Registration and Political Education for the SCLC in 1965): And we had organized to the best of our ability. I can't think of another time in the civil rights movement when the staff was so committed and worked so hard, and there was no playing around. I never will forget when the program ended and I guess about 45 minutes I walked out on those grounds and I was really crying and everybody had gone. And just a lot of people and just the wind blowing. It just looked like—it was really a miracle. . . . (inaudible) it was like a miracle.

Then I went back inside the [Dexter Avenue Baptist] church [in Montgomery]. The girl came out screaming, saying I had a telephone call. And Mrs. Liuzzo, who had been down there about three or four days, they killed her. And so that threw us back in gear.

But I don't think anything has happened in America that shook the conscience of this nation. I don't think there's anything that's ever happened in the history of America that has more awakened America and developed as much support [as] that Selma to Montgomery march.

Reading Review Questions:

-

What role did television play in the two Selma to Montgomery marches?

-

What tactics other than marches did these civil rights activists use?

-

How many of the people quoted here were local residents? How many were from national organizations? What did each group of people bring to the movement? What roles did they play?

-

What was the civil rights outcome from the Selma to Montgomery marches?

-

These quotes are taken from individuals involved in organizing the marches; what do you think might be the benefits or drawbacks of using these sources? How do you think people who weren’t directly involved might have described these marches?

Activity: Voting Rights

The right to vote continues to be contested, and state and district policies impact who can vote. Have participants research your area’s voting regulations. Ensure that participants use credible sources. Questions to research include:

-

Can all voters get a mail-in ballot?

-

Are there any voter ID-laws? What kind of identification do you need to vote?

-

Are there early voting polling places?

-

How many voting locations are there? Where are they located?

-

Can those convicted of a crime vote once they have served their sentence?

-

How do you register to vote? Is there same-day voter registration?

-

Did voting laws change due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

Do polling places have hours that extend before and after standard work hours (9:00 AM – 5:00 PM)?

After students have researched these questions, have them reflect on the following questions:

-

Which groups of people have the easiest time voting and getting their votes counted with current policies in place?

-

Which groups of people would have the hardest time voting and getting their votes counted? What laws or policy limit their ability to vote?

-

In general, are these voting rules help or harm people who are trying to vote? Are there some people they help and some people they harm?

-

Of any rules that are helpful, which ones do you believe are the most important to preserve?

-

Of any rules that are harmful, which ones do you believe are the most important to be changed?

-

What are some ways to increase voter turn out or make it easier to vote in your community?

Wrap-up:

-

Why do you think voting rights are so important? What happens if a portion of the population cannot vote, or has difficulty voting?

-

Is there a legacy of civil rights activism in your community? Were there civil rights protests in your community during the 1950s and 1960s? Have there been protests more recently?

-

Why are the Selma to Montgomery marches important to learn about today? How did they impact the country? How did they impact your community?

-

What do you feel is missing in this retelling of the Selma to Montgomery march? What would you like to learn more about?

Footnotes:

1 Quoted in Taylor Branch, At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-1968 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 170.

2 The Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division website (accessed June 20, 2018).

This reading was compiled from the following oral history interviews, conducted for the National Park Service by Edwin Bearss, NPS Chief Historian, and others: Marie Foster, Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail Oral History #512, 514-515 (September 5, 1991); John Lewis, #501-502 (July 11, 1990); F. D. Reese, #510-511 (September 4, [1991]; Amelia Boynton Robinson, #524-527 (September 10, 1991); Albert Turner, #507-509 (September 4, 1991); Reverend C. T. Vivian, #516-519 (September 6, 1991); Jamie Wallace, #504-506 (September 4, 1991); and Hosea Williams, #520-523 (September 6, 1991).

Additional Resources:

Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail

This website contains information on the historic trail that marks the march’s route from Selma to Montgomery. It also provides more information on the larger fight for voting rights.

“We Shall Overcome” National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

This on-line travel itinerary provides useful essays on the modern civil rights movement and information on places across the U.S. that are listed in the National Register of Historic Places for their association with the movement, including Brown Chapel AME Church.

Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum: Civil Rights

The Johnson Library website includes a section on civil rights that provides primary documents and activities associated with the Selma to Montgomery March.

Alabama Department of Archives and History

This website contains a lesson plan on the march, including reproductions of historic newspaper accounts and a resolution passed by the Alabama State Senate decrying the role of outside agitators and asking all “loyal citizens of the State” to avoid the march route.

Last updated: May 9, 2023