Last updated: May 9, 2023

Lesson Plan

The Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights March: Shaking the Conscience of the Nation

- Grade Level:

- Middle School: Sixth Grade through Eighth Grade

- Subject:

- Literacy and Language Arts,Social Studies

- Lesson Duration:

- 90 Minutes

- Common Core Standards:

- 6-8.RH.2, 6-8.RH.3, 6-8.RH.4, 6-8.RH.5, 6-8.RH.6, 6-8.RH.7, 6-8.RH.8, 6-8.RH.9, 6-8.RH.10, 9-10.RH.1, 9-10.RH.2, 9-10.RH.3, 9-10.RH.4, 9-10.RH.5, 9-10.RH.6, 9-10.RH.7, 9-10.RH.8, 9-10.RH.9, 9-10.RH.10

- Additional Standards:

- US History Era 9 Standard 4A: The student understands the “Second Reconstruction” and its advancement of civil rights.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies from the National Council for the Social Studies - Thinking Skills:

- Remembering: Recalling or recognizing information ideas, and principles. Understanding: Understand the main idea of material heard, viewed, or read. Interpret or summarize the ideas in own words. Applying: Apply an abstract idea in a concrete situation to solve a problem or relate it to a prior experience. Analyzing: Break down a concept or idea into parts and show the relationships among the parts. Creating: Bring together parts (elements, compounds) of knowledge to form a whole and build relationships for NEW situations. Evaluating: Make informed judgements about the value of ideas or materials. Use standards and criteria to support opinions and views.

Essential Question

What methods have Americans used to secure their civil rights? What challenges have they faced?

Objective

1. To identify the methods Alabama, and other states, used to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote;

2. To describe the events during the marches of March 7, March 9, and March 21-25, 1965;

3. To analyze the roles played by local activists and national organizations in the voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama;

4. To trace the effect Selma had on Federal voting rights legislation;

5. To identify surviving places in the local area associated with civil rights.

Background

Time Period: 1820s to early twentieth century

Topics: This lesson could be used to understand the modern Civil Rights Movement and the legacies of Reconstruction. It could also be used to enhance lessons about citizenship, forms of political participation, civil rights, and racial violence.

Preparation

Millions of people all over the United States were watching television on Sunday night, March 7, 1965, when their programs were interrupted with shocking images of African American men and women being beaten with billy clubs in a cloud of tear gas. Attempting to march peacefully from the small town of Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, the state capital, to protest a brutal murder and the denial of their constitutional right to vote, six hundred people were attacked by state troopers and mounted deputies dressed in full riot gear. ABC interrupted its broadcast of the movie Judgment at Nuremberg to show the violence, suggesting to many a parallel between the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany and the treatment of blacks in the South. Most viewers had never heard of Selma, but after March 7, they would never forget it.

Eight days after “Bloody Sunday,” President Lyndon Johnson made a famous and powerful speech to a joint session of Congress introducing voting rights legislation. He called the events in Selma “a turning point in man's unending search for freedom,” comparing them to the Revolutionary War battles of Concord and Lexington. On March 21, more than one thousand people from all over the United States again left Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma and set out for Montgomery. This time they were watched over by regular Army and Alabama National Guard units ordered by President Johnson to protect the marchers against further violence. At the successful completion of the march on March 25, Martin Luther King, Jr., addressed a crowd estimated at 25,000 in front of the Alabama State Capitol, quoting the Battle Hymn of the Republic: “His truth is marching on.” Many of the same people who had seen the earlier violence saw or heard the speech.

Five months later, on August 6, 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which some call “generally considered the most successful piece of civil rights legislation ever adopted by the United States Congress.”

This lesson explores some of the methods the State of Alabama used to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote and how community leaders in Selma worked together with Martin Luther King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and other national civil rights organizations to remove those restrictions. It discusses Brown Chapel in Selma, where the march began, and the State Capitol Building in Montgomery, where the march reached its triumphant conclusion.

Some of the participants in the events of March 1965 are still alive to tell their stories. This lesson is based, in part, on a rich trove of oral histories. It illustrates the importance of the testimony of eyewitnesses to history—as well as some of the difficulties in using this type of evidence.

Lesson Hook/Preview

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

United States Constitution

Ratified February 2, 1870

In 1965, African Americans in the United States had possessed the theoretical right to vote for almost a hundred years. Under Reconstruction in the 1870s, many black men in the South did vote. Some who had been slaves only a few years before were elected to local and, in some cases, national office. By the turn of the 20th century, however, white “Redeemer” governments had reclaimed the legislatures in former Confederate states and adopted new constitutions disenfranchising African-American voters. Black citizens attempting to exercise their constitutional right to vote encountered barriers that they often found insurmountable. These included poll taxes, literacy tests, clauses that limited voting to people whose ancestors had voted in the past, and party primary elections that were limited to whites.

Men and women working for civil rights had long recognized that gaining the right to vote was central to achieving full citizenship for African Americans. The long-established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had successfully challenged the restrictive primary and other obstacles to black voter registration, but other, younger organizations had grown impatient with the slow rate of progress through the legal system. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) turned to mass demonstrations and nonviolent acts of civil disobedience. Martin Luther King, Jr., the charismatic leader of SCLC, became internationally known for promoting, supporting, and participating in nonviolent direct action seeking civil rights for African Americans. In December 1964, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming, at age 35, the youngest person ever to receive that honor.

Peaceful demonstrations attracted media coverage, particularly when they were met with violent opposition. This helped generate the widespread support necessary for the passage of civil rights legislation. This legislation, particularly the Civil Rights Act of 1964, sought to achieve equal education, access to places of public accommodation and transportation, and equal employment. In 1965, however, most Southern blacks were still unable to overcome the obstacles set up to prevent them from voting.

Procedure

Getting Started Prompt

Map: Orients the students and encourages them to think about how place affects culture and society

Readings: Primary and secondary source readings provide content and spark critical analysis.

Visual Evidence: Students critique and analyze visual evidence to tackle questions and support their own theories about the subject.

Optional post-lesson activities: If time allows, these will deepen your students' engagement with the topics and themes introduced in the lesson, and to help them develop essential skills.

Vocabulary

Reconstruction

segregation

disenfranchisement

civil rights

Additional Resources

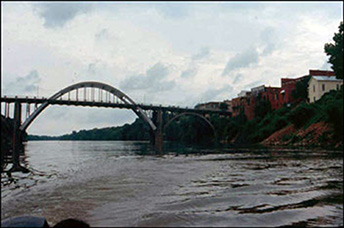

Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail

This website contains information on the trail and on the Lowndes County Interpretive Center, opened in 2006. It also is a rich source of materials on the march developed by the National Park Service as part of the “Never Lose Sight of Freedom” program. The program includes a brief history of the march, additional lesson plans, and links to a wide variety of primary sources, including oral histories, photographs, audio and visual files, and information on an educational dvd.

“We Shall Overcome” National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

This on-line travel itinerary provides useful essays on the modern civil rights movement and information on places across the U.S. that are listed in the National Register of Historic Places for their association with the movement, including Brown Chapel AME Church.

Historic Places of America’s Diverse Culture

The National Register of Historic Places online itinerary Places Reflecting America’s Diverse Cultures highlights the historic places and stories of America’s diverse cultural heritage. This itinerary seeks to share the contributions various peoples have made in creating American culture and history.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress “Today in History website for March 7 includes information on the Selma to Montgomery March, on Congressman John Lewis’s career after 1965, and on the 35th anniversary commemoration of the march on March 7, 2000.

Photographs, drawings, and written materials in the Historic American Buildings Survey Collection record the architecture and early history of the Alabama State Capitol.

Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum: Civil Rights

The Johnson Library website includes a section on civil rights that provides primary documents and activities associated with the Selma to Montgomery March.

Alabama Department of Archives and History

This website contains a lesson plan on the march, including reproductions of historic newspaper accounts and a resolution passed by the Alabama State Senate decrying the role of outside agitators and asking all “loyal citizens of the State” to avoid the march route.

Making Sense of Oral History

This website, maintained by the George Mason University program “History Matters,” provides useful information on using, interpreting, and evaluating oral histories.