An Innovative Technology of War

Wig Wag: The Army's "talking flags"A signal system using flags and torches was invented by a U.S. Army surgeon, Major Albert Myer, in the 1850's and adopted by the U.S. Army in 1860. Myer's system permitted messages to be sent across areas where telegraph wires were unavailable. To the untrained observer, the flagman appeared to be merely waving a flag back and forth, hence the name "wig wag." Myer became the U.S. Army's first chief signal officer. Myer's assistant during the development of the wig wag system was an exceptional young officer named Lt. E. Porter Alexander. Alexander was a Georgian who resigned his commission in the U.S. Army to fight for the Confederates. He helped organize, equip, and train the Confederate Signal Service. Thus both armies used essentially the same signal system, so encoding messages became critical.

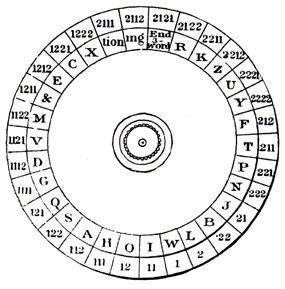

Codes and CiphersTwo forms of code were used: initially a four-element code and later, a two-element code. In the four-element code, movements of the flag conveyed the numerals 1, 2, 3, or 4 which were grouped to stand for letters and sometimes words or phrases. The letter "B" might be "1423," for example. By the end of the war, a two-element code was in use. Letters were formed using just the numerals 1 and 2, as dots and dashes were used in telegraphy. A "1" was indicated by moving the flag from the vertical to the sender's left: a "2" indicated by waving to the sender's right. So "A" might be "12" or "X" sent as "1221." The motion of the flag was an integral aspect of the wig wig system enhancing readability of the signal.

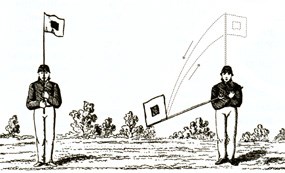

Flags, Torches and TelescopesSignal parties used different combinations of flag size, color, and staff length to increase the readability of the signal. Signal kits issued by the U.S. Army included seven different flags in three different sizes--2'x2', 4'x4', and 6'x6'. The 2-foot flag, permitted sending a signal over short distances in tactical situations where the flagman had to lie down or signal from cover. The 4-foot flag was the most commonly used. The 6-foot flag was employed for extra long distances. Color combinations were, red or black with a white center square and white with a red center square. In any given situation the color selected was that which gave the best contrast to the background. The flag staff was made of hickory in 4-foot sections. Myer's Manual of Signals stated that with a 12-foot staff and 4-foot flag, signals "are easily read at a distance of 8 miles at all times, except in cases of fog or rain. They are read at 15 miles on days and nights ordinarily clear." Special torches, fueled with turpentine, were used to send signals at night. One torch was placed in the ground. A flying torch was mounted on the end of the signal staff. By moving the flying torch form side to side relative to the motionless foot torch, the "1" or "2" could be read. Telescopes and field glasses were an essential part of a signal party's equipment. Union officers were accountable for their equipment and were under strict orders not to let any fall into enemy hands.

Library of Congress A Signal Party on Duty in the Field

Only the officer understood the code, and he was responsible for encoding and decoding messages. The enlisted men would flag the signals and assist in reading incoming signals which were given to the officer for translation. Signalmen were selected by examinations and were generally more educated. Commissioned officers were tested in reading and writing, composition, arithmetic, chemistry, natural philosophy, surveying and topography. Not only were they expected to serve as communicators, they also assisted commanders with reconnaissance and surveillance by virtue of their location at high points on the terrain and their mobility. The life of a signalman could be behind the lines enjoying good food and the comfort of a commander's headquarters—or in advance of the army exposed to the elements in remote and isolated locations, experiencing hardship and danger. Signal Stations During the Battle

Gloskoski's Elk Mountain station sent the most famous signal of the battle. Late in the afternoon this party observed Lt. General A.P. Hill's division of Confederates approaching the battlefield after its long march from Harpers Ferry. The Elk Mountain station sent an urgent message to Gen. Burnside, "Look well to your left. The enemy are moving a strong force in that direction." Confederate signalman were also active during the battle and official maps of the battlefield indicate a CSA signal station was located behind the West Woods.

Library of Congress |

Last updated: September 15, 2023