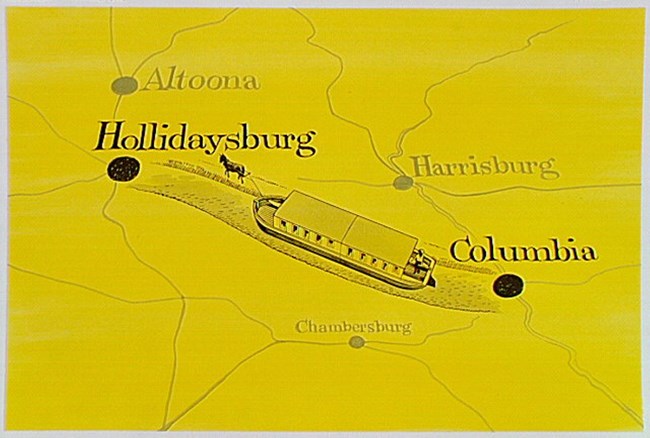

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center Hollidaysburg was a small backwoods village in the early 1820s. Founded in the years after the Revolution, the settlement's growth was hampered by its location in the rugged remoteness of the Allegheny foothills. The Huntingdon, Cambria, and Indiana Turnpike, a narrow dirt road really, ran through the heart of town, bringing an occasional pack train of horses or a Conestoga wagon. Its population in 1827 was about 76. This all changed with the coming of the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal. Within ten years, Hollidaysburg had a population of 3,000 and growing. From a tiny frontier village to an inland seaport, this all took place within a five-year period. It all happened because a farmer wouldn't sell his land to the Pennsylvania Canal Commission. When the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania began letting contracts for the building of the state's canal system, work commenced on the two ends of the canal and progressed steadily toward the middle. No one was sure how they were going to lift canal boats over the Allegheny Ridge until the two divisions of the waterway were within just a few miles of the mountains. After abandoning the idea of digging a four-mile tunnel through the mountains, the Allegheny Portage Railroad was accepted as the best method for getting the boats across the mountains. Once this course was set, it was necessary to find good locations for two canal basins -- one on the eastern side of the ridge to take the boats out of the canal and one on the western side to refloat them. The western basin location was easy. The little town of Johnstown was at the confluence of the Stony Creek and Little Conemaugh rivers, which supposedly would ensure an adequate water supply for the basin. On the eastern side, it was determined that the hamlet of Frankstown would be the ideal location for the second basin. However, the site selected by the canal engineers was located on the property of a farmer who either didn't like the idea of change or who was a little too greedy to accept the price he was offered for his land. In any event, the canal engineers turned elsewhere, finally determining that Hollidaysburg was an acceptable alternative. Moreover, the site had the highest elevation that could possibly be used to construct the basin. And so it began. Hundreds of workers were recruited from the surrounding countryside and from distant cities to begin digging the canal and cutting the stone for related structures. Their arrival alone mushroomed the population of the little town. It is hard to imagine how they accomplished the task before them. There were no steam shovels, bulldozers, or even electricity to allow them to work through the night. Instead, there were merely men and their muscles --with a little help from wheelbarrows and horse-drawn wagons to haul away the excavated dirt. When they were done, a gigantic artificial pool emerged from the bottomland along three branches of the Juniata River converging nearby. The water for these streams had their sources among the rocks and trees of the mountains in the distance. The main basin itself was six feet deep, 120 feet wide, and two miles long. There were actually three interconnected basins in the port complex. The main basin was located where railroad yards are now. This was connected by a 600-foot canal segment to a smaller basin located just below present-day Juniata Street. The third pool was really a feeder reservoir for the other two. It was located near the modern intersection of Route 22 and Allegheny Street in Hollidaysburg. Once the basins were filled with water, Hollidaysburg's transformation into a seaport was only a matter of time. At its height, the canal brought a boat into the port every 20 minutes. Boat slips and docks were built to handle the freight streaming into the area. Large warehouses and freight forwarding houses were erected near the docks. Hotels and taverns catering to boatmen and travelers arose among the modest houses in the town. At first, canal boats were unloaded on the Hollidaysburg wharves, their freight and passengers transferred to railcars for the trip across the mountains on the Portage Railroad. A later innovation, the three- or four-section canal boat, could be hauled out of the water, disassembled, and placed on "trucks," small metal-wheeled undercarriages that ran on rails. After completing their journey over the mountains, the section boats were reassembled at the Johnstown canal basin and continued on their watery way. The large freighters made frequent appearances in paintings from the time. However, the passenger packets appeared most frequently in books and essays. Their human cargo preserved the canal saga in words. Philip Nicklin made a cross-state journey in 1835 that provided the subject matter for "A Pleasant Peregrination Through the Prettiest Parts of Pennsylvania, Performed by Peregrine Prolix." This is how Nicklin described Hollidaysburg at the time: "Hallidaysburg [sic] has the air of a new clearing, and looks so unfinished, that one might suppose it to have been built within a year. Its site is good, rising gradually from the basin to a pleasant elevation. Many substantial buildings are going up, and it is evident that rapid increase is the destiny of the town." While passenger traffic made up a good deal of the business flowing through Hollidaysburg, manufactured goods contributed to the bulk of trade. Pianos, flour, cement, nails, and everything in between traveled on canal freighters. There were also a number of boats converted into floating stores. The owners of these establishments sent riders ahead to announce the imminent arrival of the boats. Although Hollidaysburg housewives firmly believed they were getting great bargains on the merchandise sold from the boats, the town's storekeepers were less than enthusiastic. Written accounts from the canal period mention the "unfair advantage" the floating stores had at the expense of Hollidaysburg's business proprietors. Along with the commercial bustle near the basin, small iron foundries and machine shops made their appearance in back alleys in Hollidaysburg and Gaysport, the area just to the south and across the Beaver Dam branch of the Juniata River. Here, implements and tools were fabricated from pig iron produced in furnaces in the surrounding hills. One of these fledgling companies, the McLanahan Corporation, continues in operation today. Tens of thousands of people passed through Hollidaysburg during the canal era. European immigrants, native-born Americans, '49ers during the Gold Rush -- they all made their way westward via the canal or the rough turnpikes crisscrossing the mountains. By the late 1850s, it became apparent that the canal system was obsolete. In 1857, the Pennsylvania Canal was bought by the Pennsylvania Railroad. Shortly thereafter, the Allegheny Portage Railroad was dismantled and the Hollidaysburg basin's days were numbered. A photo from 1863 shows the basin still in use, although boat traffic is nearly absent. The boat slips, warehouses, and wharves are nearly deserted. However, the basin continued in operation until about 1875, mostly serving the needs of area farmers and manufacturers. One of the frequent floods along the Juniata destroyed much of the infrastructure associated with the canal in this part of Pennsylvania. Repairs were too expensive and plans were made to abandon the section between Hollidaysburg and Huntingdon, some 30 miles east of the basin. After this portion of the canal was finally closed, the great inland port was drained of water and the massive basin was filled in with cinders, probably the by-product of the iron furnaces surrounding Hollidaysburg. A way of life for hundreds of people for 50 years came to an end.

|

Last updated: January 25, 2026