On the scale of war as waged in Europe during the age of Napoleon, the War of 1812 was a minor affair. In 1812, as Napoleon was invading Russia with a half million men, the United States on the other side of the world was trying to conquer Canada with forces numbering about one-tenth of a percent of the Grande Armée’s size. While individual European battles counted casualties in the tens of thousands, about 6,000 Americans were killed or wounded during the entire War of 1812.

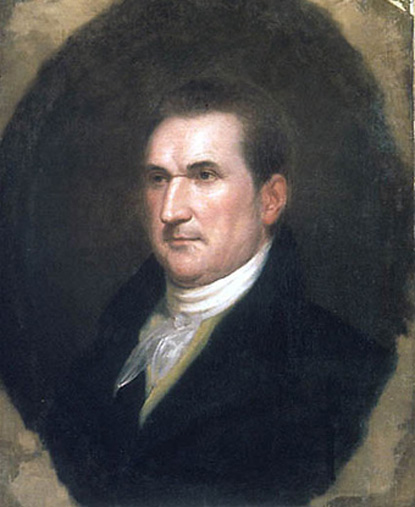

Political dissent coincided with appalling military unpreparedness, a problem evident from the top down. Many ranking generals were aging relics of the Revolutionary War.

NPS

Americans could count themselves fortunate that the British military was preoccupied with Napoleon for most of the Anglo-American conflict. That good fortune saved the country in the first two years of the fight. Broad disunity and sectional discord in New England made the War of 1812 one of the most bungled military ventures in the Republic’s history. Neither the country nor its politicians could agree on the wisdom of challenging Britain, and these deep divisions hobbled the war effort. Pro-war congressmen were sufficiently organized, voluble, and energetic to earn the label war hawks, but military disasters limited their ability to shape events. Steeped in the tradition of a passive executive, President James Madison was temperamentally unsuited for the demands of wartime leadership. His subordinates were often incompetent placeholders out of touch with the mood of the country, which was divided between apathy and disagreement over the wisdom of the war in the first place, let alone how to prosecute it.

Political dissent coincided with appalling military unpreparedness, a problem evident from the top down. Many ranking generals were aging relics of the Revolutionary War. William Hull abandoned a meandering invasion of Upper Canada and wound up surrendering Detroit in August 1812 without firing a shot, placing the entire Old Northwest under British control when the war was only a few weeks old. Also that August, Henry Dearborn, senior major general in charge of the northeast theater from the Niagara River to the New England coast, without a shred of authority, signed an armistice with Canada’s governor-general, an agreement Madison had to repudiate. James Wilkinson, a self-serving opportunist, quarreled with colleague Major General Wade Hampton and superior Secretary of War John Armstrong, dooming the 1813 assault on Montreal.

Although promising officers would emerge toward the end of the conflict, younger generals were often no better than their antiquated counterparts. Early in the war, New York militia general Stephen Van Renssalaer was woefully inexperienced and abashedly resigned after losing the Battle of Queenston in October 1812. His successor, regular army general Alexander Smyth, had a talent for drafting bombastic proclamations but could only manage farcical invasion attempts across the Niagara River before his removal from the service. And Madison put young William Winder in charge of Washington’s defense in the summer of 1814 because he was politically important (Maryland governor Levin Winder was his uncle), rather than a sound military choice. Within six weeks the capital was occupied by the British and in flames.

Part of a series of articles titled Land Operations in the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015