The divisions between political parties in the early 19th century seemed almost insurmountable. Instabilities in politics threatened not only the effectiveness of the government, but its very stability. The War of 1812 was the first American civil war. New England threatened to secede from the union.

“The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States.” James Madison, Federalist #10

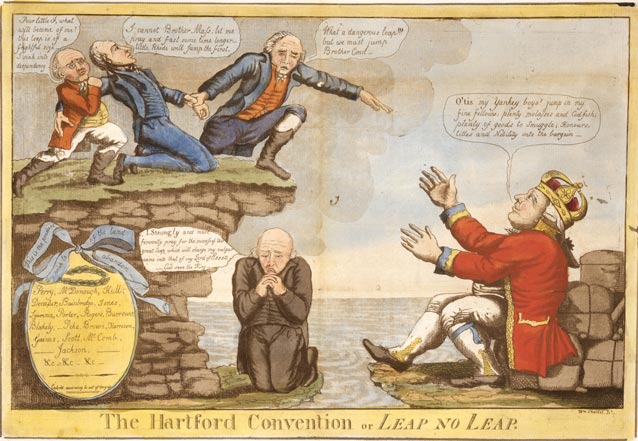

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

One of the very dangers that James Madison warned against when he wrote in support of the U.S. Constitution haunted his presidency. “The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States,” Madison wrote in Federalist #10, “but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States.”

Madison’s own political supporters in the south and west avidly kindled such a “flame” when they loudly and persistently pushed the government toward war, citing British infringements on shipping, damage to international prestige, and Indian attacks on the frontier.

The Federalist Party, on the other hand, still strong in several New England states, thought that war with Great Britain would prove to be costly and damage commerce. They not only opposed war but discouraged enlistments and war funding. Sure enough, after several years of lax enforcement in New England, the British tightened their blockade, occupied the territory of Maine, and invaded the Champlain Valley.

In response to war costs levied by the federal government, 26 delegates from Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Vermont met at Hartford, Connecticut, in late 1814. These “secessionists” were convinced that New England had a “duty” to assert its authority over unconstitutional infringements on its sovereignty, though the official convention proceedings revealed a relatively moderate stance.

Bad timing doomed the Hartford Convention. Just as the commissioners formalized their demands, the war ended, forever tainting the convention and the Federalist Party with accusations of disunion and treason. Then, as now, political satirists spared the sensibilities of few politicians.

Was Madison correct after all? Could a well-designed republic control the spread of factions and avoid a “general conflagration”?

Last updated: March 30, 2015