.gif)

Historic Roads in the National Park System

MENU

Understanding and Managing Historic Park Roads

|

Historic Roads in the National Park System

|

|

| PART I: HISTORY |

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PARK ROADS

AUTOMOBILES: YEA OR NAY

While interest in autotourism grew throughout the United States. in the early 20th century, the official stance of the Department of the Interior was that no automobiles would be allowed in the national parks. That started to change in 1907. Hot Springs Reservation was the first federal reservation — set aside in 1832 for its natural resources. [34] During the 1890s the reservation underwent considerable landscape development and improvement under the auspices of the War Department. Part of that development included the construction of carriage roads that wound up the mountainsides to overlooks and an observation tower.

In 1907 W. Scott Smith, the superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation, wrote to the secretary of the interior and recommended keeping automobiles off the mountain roads of the federal reservation "in the interest of the protection of human life." He stated that the only automobile company in Hot Springs had ceased doing business there, that only three automobiles existed in Hot Springs, and that only one of them had enough horsepower to ascend the mountain roads. He also argued that allowing automobiles on mountain roads would spoil the spa experience by depriving many visitors of taking carriage or horseback rides on the mountain roads. [35] A handwritten note on that piece of correspondence stated "7/11 Letter to Superintendent, denying." That small, pencilled note from 1907 eventually changed the way in which most visitors experienced national parks. Hot Springs was the first federally protected area to officially allow automobiles.

In 1908 the chairman of a group called the California Promotion Committee officially requested that automobiles be allowed in the national parks. In response to that request the first assistant secretary replied that automobiles were only allowed in Mount Rainier National Park, and that their use was limited by a series of regulations. The assistant secretary continued: "It has been the invariable rule of the Department to prohibit the use of automobiles in the other National Parks." [36] The exceptions at Hot Springs and Mount Rainier, however, had opened the floodgates.

Despite that official ruling, the public pressure for providing automobile access to the national parks was building. Less than a year later the secretary of the interior requested the opinion of the superintendent of Yellowstone on the advisability of allowing automobiles into Yellowstone. The park's superintendent, Maj. Harry Benson, had 13 years of park duty under his belt, and he adamantly counseled against it. He replied: "The character of the roads, the nature of the country, and conditions of the transportation in this park render the use of automobiles not only inadvisable and dangerous, but to my mind it would be practically criminal to permit their use." He based his reasoning on the potential conflicts between horses and automobiles. The transportation companies in the park at the time used between 1500 and 1800 head of horses for their stages during the tourist season, and he did not believe it was possible to get the animals accustomed to seeing automobiles. He was concerned that up to one-third of the stagecoaches pulled by four-up teams might be overturned when the animals were spooked by an automobile. Benson also cited that the two army superintendents who commanded Yellowstone before he did — Col. Pitcher and Lt. Gen. Young — both recommended that automobiles be prohibited from entering the park. [37]

The push for automobiles in the national parks continued, however. A motoring club in Montana wrote to the secretary of the interior recommending the construction of a road to the boundary of Glacier National Park at Belton. Because private donations were being used — the road was being constructed with money out of the pockets of the club members — the letter requested that automobiles be allowed to enter the park. Also autoists wrote that "it would be a great thing if one [a road] was constructed inside the Park around the Lake and in time extended over the mountain pass so people could get in from the East." [38] Then the secretary began hearing from senators who had been contacted by their constituents, and additional pressure was on. Sen. Henry L. Myers contacted the secretary and requested his support of road development and automobile access for Glacier National Park after he received a letter from Fred Whiteside, a constituent from Kalispell, Montana. Whiteside wrote:

There is a small matter I would like to have you look into when you get to Washington. The government is planing [sic] to expend considerable money in the building of a wagon road in the Glacier National Park, which is in this county, and I believe the regulations covering the park will be formulated by the Secretary of the Interior very soon. We are very anxious to have the regulation so framed that automobiles may be used on the roads in the Park. In the Yellowstone Park nothing but horses are allowed, but we believe we have now reached the stage of civilization where it will be better to use automobiles even if the horses are to be left out. [39]

Whiteside got his wish, and the regulations for allowing automobiles into Glacier National Park were drafted the following year, based on those for Mount Rainier.

The Department of the Interior was extremely interested in attracting more people to national parks, and increasing visitation was one of the chief topics at a conference on national parks held in Yellowstone in 1911. Representatives from the railroads argued that train ticket prices were cheap enough to foster tourism in the parks, so they saw no additional need for the railroads to provide additional aid. In their view, the biggest obstacle to increased visitation was limited automobile access in national parks."

AUTOMOBILE CLUBS

The influence that automobile clubs had on access to national parks was exceedingly strong. The American Automobile Association tried early on to have Yellowstone opened to automobiles, but without success. Following the appointment of a new secretary of the interior, Franklin Lane, things started to change. Lane had his assistant, Stephen T. Mather, look into the possibility of allowing vehicles into the park, and Mather set up an unofficial committee to discuss the issue. On the committee were Mather, Robert Marshall (chief geographer of the U.S. Geological Survey and superintendent of National Parks prior to 1916), Colonel Brett of the U.S. Army in Yellowstone, and A.G. Batchelder who was the chairman of the executive board of the American Automobile Association. The committee developed a road-use schedule which "governed self-propelled vehicles and muscle-drawn wagons, which practically kept the two forms of travel completely apart." The AAA also pushed for the construction of connecting highways between national parks through federal aid. Batchelder wrote that "many of these road travelers will include the other national parks in a road itinerary which would be impossible of duplication in any other country in the world. Surely the day has arrived when the American will truly begin to get acquainted with his own country." [41]

Even though a few other national parks were open to the motoring public, the opening of Yellowstone to automobiles in 1915 signaled the beginning of a new era. The automobile clubs believed they had won a terrific victory over the conservative officials of the Department of the Interior, and that most people who were heading to or from the West Coast changed their itineraries to include Yellowstone National Park. One article noted that the "equine motors" in Yellowstone would have to be given a chance to get accustomed to the "invasion of these strange monsters from the outer world." But, the article went on to say, the time when all traffic in Yellowstone would be motorized was coming fast. [42] That prediction proved to be correct. [43]

In addition to the automobile clubs and their influence on providing better access to the parks' scenic wonders of America, other factors also had an effect on tourism. One of these was the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, which became a prime reason that more people were becoming adventuresome in their motorcars and exploring their nation. Correspondence of the period, however, indicated that the political base of the automobile clubs was the principal factor that opened the parks to automobiles.

AUTOMOBILE REGULATIONS

Allowing vehicles into national parks required restrictions. Road conditions could vary tremendously in just a short period of time depending on weather. The conflicts between horse-drawn vehicles and automobiles on the same narrow roads pointed to a need for regulation. Despite the problems that existed in with allowing automobiles into national parks, the department had become more flexible by 1910-11. The office of the secretary of the interior drew up regulations governing the admission of automobiles to Crater Lake, Mount Rainier, General Grant, and Glacier National Parks. The secretary's office first wrote the regulations following a boilerplate approach in which the general rules were similar, but they contained slight variations that tailored the regulations to the individual parks.

Each set of regulations began by citing the park's enabling legislation and stating that the superintendent needed to provide written permission for entry into the park. Often automobiles were permitted on roads only during certain hours — about three hours in the morning and three in the afternoon — to minimize potential conflicts between automobiles and stages. Yellowstone's regulations, for instance, included a very tight schedule for road use. All of the early driving regulations required automobiles to pull over to the outside of the roadway regardless of direction of travel when teams passed. Also, when teams approached automobiles were required to stop until the team passed or until the teamster determined it was safe for his team to proceed. The speed limit on park roads was 6 miles per hour except on straight stretches where no teams were in sight. In those areas drivers were allowed to increase their speed to no greater than 15 miles per hour. Because the roads were so narrow and often winding, the regulations dictated that drivers had to honk their horns at every turn so that teams would know that automobiles were approaching. [44]

What started as a trickle of vehicles admitted to national parks grew to a steady stream. The Department of the Interior first admitted automobiles to Hot Springs in 1907 and Mount Rainier in 1908, followed by General Grant in 1910, Crater Lake in 1911, Glacier in 1912, Yosemite and Sequoia in 1913, and Mesa Verde in 1914. By 1916 the department allowed them on a limited basis in Rocky Mountain, Platt, Wind Cave, Sullys Hill, and Casa Grande. Yellowstone National Park's concessioner phased out the horse-drawn stages and replaced them entirely with automobiles during the 1917 season, only two years after automobiles were allowed into the park. [45]

|

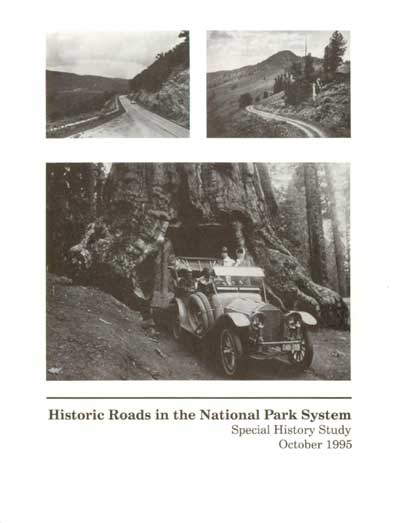

| Fig. 1. The army completed construction on this section of road near Nisqually Glacier in 1908. In this 1912 photograph, the rugged condition of the road was evident. Maj. Hiram Chittenden, who had been in charge of road construction in Yellowstone, supervised construction of this road. Horse-drawn carriages, bicycles, private automobiles, and concessioner touring cars were allowed access. (National Archives, Record Group 79) |

SEE AMERICA FIRST

In 1914 Europe was at war, and in August of that year John Wilson, president of the American Automobile Association, walked down the gangway of a luxury liner as it returned home from a trip abroad. His fellow passengers on the ship were people fleeing the war zone. As he stepped off the ship, Wilson wryly stated: "It is my guess that in 1915 many Americans who annually motor abroad will become much better acquainted with their country." [46] He was right.

He believed that if Americans stayed home for the projected duration of the European troubles — a "year or so" he predicted — that they could view the scenic wonders of their own country. Also, he noted that the natural marvels of the United States compared very favorably with those of Europe. He realized that access to Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon was difficult, but he openly stated that more use by motorists would increase the demand for greater federal involvement in road construction and improvement. Even more important, however, Wilson noted the importance of roads in the war in Europe, and he believed that road development here would strengthen the nation. [47]

EARLY INTERBUREAU COOPERATION

As early as 1905 the Office of Public Roads was assisting the U.S. Forest Service in the development of roads in national forests. In 1912 the two bureaus worked out a formal agreement to handle roadwork. Since 10% of forest revenues were allocated for roadwork, the Office of Public Roads had a good working budget for Forest Service lands. [48]

The Office of Public Roads also began doing some work in and around national parks. In 1910 a private organization called the Crater Lake Highway Commission was working on promoting access to and around Crater Lake National Park. They requested a road expert out of the Office of Public Roads to supervise construction of an approach road through Crater Lake National Forest to Crater Lake National Park. Also, they requested that the OPR employee plan a system of roads and trails for the park. This access road was financed through private subscriptions and county funds instead of through the 10% Forest Service fund. [49]

This process of using private funding to assist in the development of national parks was a fairly common practice, and the use of donations for road construction was only one way in which monies were spent. In the early years of the National Park Service, Stephen Mather and Horace Albright cultivated powerful and often philanthropic support groups that included congressmen and senators, presidents, and businessmen and used them to benefit the agency. When Congress refused to approve an appropriation for the acquisition and reconstruction of the Tioga Road that crossed the Sierra in Yosemite National Park, Mather believed so much in its acquisition that he dug into his own pockets and also loosened the purse strings of his cohorts to finance it. [50]

Work in forest and park areas increased quickly, especially with the combination of federal and private funds. In 1914 Logan Waller Page, the director of the Office of Public Roads, sent an engineer and a survey party to Yosemite to begin work there. So much work existed that Page established a separate Division of National Park and Forest Roads within the Office of Public Roads to handle the projects, and he placed T. Warren Allen at the head of the new division. [51] That same year Assistant Secretary of the Interior Adolph Miller wrote to the superintendent at Mount Rainier that he had established a tentative plan of cooperation between the Department of Agriculture and the Department of the Interior for the construction and maintenance of roads in national parks. That tentative plan grew into the first cooperative agreement between the Office of Public Roads and the Department of the Interior. Also the assistant secretary stated that Mr. Allen was on his way to visit Mount Rainier with an idea of eventually placing a survey party there to work on park roads and trails. [52] These projects laid the groundwork for the decades of cooperation between the two bureaus.

NEXT >>>

Last Modified: Mon, Aug 23 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/harrison2/shs2.htm

![]()

Top

Top