|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park |

|

| PART II: MANAGEMENT OF THE ALASKA UNITS |

Chapter 5:

General Park Administration, Skagway

Getting Started

Less than two weeks after President Ford signed Public Law 94-323, which authorized Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Regional Director Russell Dickenson met with his Pacific Northwest Region associates and laid plans for the new park. No action could be taken until Washington's official notification came through. Upon receipt of that notice, the Alaska park units would become the concern of Bryan Harry, the Alaska Area Office Director. Dickenson recognized that the interim park perspective called for the Seattle and Alaska units to be managed by the same individual. For the time being, however, he decided that the Seattle unit would be directed from the regional office. [1]

On August 17, the agency's Acting Associate Director for Legislation finally issued the activation memorandum to the regional director. Dickenson, in turn, sent the memo on to Bryan Harry in Anchorage on September 14, directing him "to establish the Park in accordance with the provisions of P.L. 94-323, by the appropriate programming, staffing, operation, and overall administration." Meanwhile, an official from the regional office ordered a 750-copy reprinting of the park's May 1973 master plan, updated to include a copy of the recently-passed legislation. The revised master plan was completed in October. [2]

Area officials recognized that the first task to be undertaken was the appointment of a person to evaluate and acquire buildings and lots in Skagway's historic district. A historical architect was the logical person for the work. Officials were unsure, however, whether to appoint that person as a superintendent as well. In mid-July, the regional director assigned his associate, James B. Thompson, to look for a historical architect to be the "manager" in Skagway. [3] Then, a month later, the chief historical architect at the agency's Denver Service Center, Vernon Smith, offered the park superintendency to one of his employees, Gary Higgins. Higgins, however, had no interest in becoming a line administrator and turned down Smith's offer. Soon afterward, it was decided that the superintendency and the historical architect should be two separate positions. Given that arrangement, Higgins accepted the historical architect position in October. He arrived in Skagway on an introductory visit in December, and on January 23, 1977 he commenced work as the park's first Alaskan employee. Thereafter, Higgins replaced Glacier Bay superintendent Tom Ritter as the agency's local contact person. [4]

Higgins worked under primitive conditions for his first few months on the job. Prior to his move, arrangements had been made to lease office space upstairs in the theater-supermarket building on Broadway north of Fourth Avenue. When he arrived, however, the office was not yet ready. As a result, for the next several months the park's de facto "office" was the living room of Higgins's apartment. [5]

Soon after Higgins began work, Richard E. Hoffman was hired as the first park superintendent. Hoffman, who had been working for the National Park Service since 1961, had been a four-year superintendent at Manassas National Battlefield Park at the time of his selection. In order to prepare for the position, he visited Skagway in February 1977. Two months later, on April 24, he began work on a full-time basis. [6]

A skeleton staff--barely sufficient for interim needs--was assembled over the next several months (see Appendix B). The first clerk-typist, Barbara Montgomery, was hired in August 1977 on a subject-to-furlough basis. Peter Bathurst, a preservation specialist who hailed from Longfellow National Historic Site near Boston, was hired as an assistant to Gary Higgins. He arrived in early November. In addition, the first seasonal workers came on board. In May 1977, two women--Janet Ross and Meg Jensen--began work as the first locally-supervised Chilkoot Trail rangers. (NPS staff had patrolled the trail since 1973, but they had worked under the supervision of Glacier Bay National Monument personnel.) Four other seasonal rangers were hired to work as the first Skagway interpreters; they consisted of Linda Chesney, Russell Plaeger, John Jackson, and Craig Juleen. All four interpreters also spent short-term stints serving as Chilkoot Trail rangers. [7]

One of the first duties assigned to the newly-appointed permanent staff was the organization of a park dedication ceremony. Planning for the event began in March 1977. Personnel from the park and the city government, who co-sponsored the dedication, invited many of those who, over the past ten years, had been significant contributors to the creation of the park. More than fifty local, state, provincial, and federal dignitaries were invited; even President Jimmy Carter reportedly received an invitation. [8]

The dedication was held on Saturday, June 4, 1977, on Broadway in front of the Arctic Brotherhood Hall. Sunshine prevailed that day, and observers noted that "the whole town turned out" for the event, many of them dressed up in Gold Rush era outfits. Among the attendees was Fairbanks resident Robert Sheldon, age 94, who had lived in Skagway during the gold rush and its aftermath. Dignitaries in the audience included U.S. Senator Ted Stevens, Yukon Commissioner Dr. Art Pearson; Mike Miller and Jim Duncan, of the Alaska State Legislature; and scores of other luminaries. [9]

The program featured a variety of speakers and musicians. The master of ceremonies was NPS Regional Director Russell Dickenson, and welcoming remarks were made by Skagway Mayor John Edwards and NPS Superintendent Richard E. Hoffman. Additional remarks were provided by Alaska Lieutenant Governor Lowell Thomas, Jr.; W. Warren Allmand, Canada's Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development; John I. Nicol, the Director General of Parks Canada; and John D. Hough, a special assistant to Cecil Andrus, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. The man chosen to give the primary address was James Smith, the Chairman of the Northern Canada Power Commission (in Whitehorse); a decade earlier, Smith had been the Yukon Commissioner when the first park studies were being completed. Music was provided by the Skagway Community Band, the Skagway Community Chorus, and the Midnight Sun Pipe Band of Whitehorse; and entertainer Larry Beck recited a poem he had written for the occasion. The sounding of a cannon, a fire bell, locomotive and steamship whistles, and the performance of a Native dance troupe rounded out the program. Visitors that day, as part of the dedication ceremonies, were invited to tour the various park buildings. [10]

One and all seemed glad to welcome the new park into existence. Skagway's residents hoped that the park would be a spur to tourist development, and voices on the national and international levels were happy to see the preservation of critical lands through which the gold rush stampeders moved. Alaskans were just as happy with the new park as outsiders. Many Alaskans during this period were fuming at the federal government's attempts to preserve tens of millions of acres in parklands via the so-called "d-2" process. But editorials across the state praised the new park. The Fairbanks Daily News-Miner noted with surprise that "we have seen a park formed at the request of Alaskans by a bill sponsored by our delegation," and pointedly observed that the park "does not extend out to cover an entire ecosystem, but simply protects an established recreational area which thousands of people will want to enjoy as long as the tales of the Klondike Gold Rush days are told." [11] The Anchorage Times offered similar praise, noting that

Even those Alaskans who oppose the idea of reshaping much of their state into a supernational park complex under various D2 land proposals can applaud the recent dedication of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in Skagway.... And there is strange irony in noting that the North that was tamed by these colorful exploiters, entrepreneurs and developers is not protected from modern-day exploiters and developers by national governments who recognize that the trail of these bold pioneers is worth preserving. [12]

The Land Purchasing Program

At the time of the June 1977 dedication, the park consisted of little more than a rented office and the buildings that the National Park Foundation had purchased for the NPS in 1971 and 1974. Those buildings, the WP&YR railroad depot and the Mascot Saloon complex, had been transferred from the NPF to the NPS in November and September 1976, respectively. The purchase price for the depot had been $122,000; for the Mascot complex, the price had been $42,722.06. [13] The park also owned a small (270-acre) triangular-shaped parcel west of the Chilkoot Trail and adjacent to the Canadian border; that parcel had been transferred from the Bureau of Land Management to the NPS on June 30, 1976 as part of a broad, interagency agreement.

The purchase of private lands, engineered by personnel in the Pacific Northwest Regional Office lands division and by Klondike Superintendent Richard Hoffman, did not begin until the spring of 1977. The master plan, published in 1973, noted that "National Park Service involvement would require the purchase and restoration of a significant number of historic structures that are now mostly vacant or used for storage." The plan envisioned that most of the buildings purchased would be restored in situ; the plan also noted, however, that "In order to achieve a more cohesive historical district, the National Park Service would relocate some historic buildings on Broadway, to bring them together for interpretive and management purposes."

The master plan, produced four years earlier, had called for the purchase of eight privately-owned buildings or lots in Skagway:

1) the Idaho Saloon, on Broadway at Third;

2) the Principal Barber Shop, on Broadway between Fourth and Fifth;

3) a lot on Broadway at Fifth;

4) a lot on Broadway between Second and Third;

5) Verbauwhede's Confectionery, on Broadway between Second and Third;

6) Boas Tailor and Furrier, on Broadway between Second and Third;

7) the Pack Train complex, on Broadway between Fourth and Fifth; and

8) the Moore Cabin, on Fifth east of Broadway. [14]

By the spring of 1977, however, changing fiscal priorities, new construction on Broadway, and raised expectations on the part of Skagway's historic building owners combined to force alterations to the above list. NPS regional office lands staff, working in concert with local park staff, made it known that they would be willing to purchase any historic building or lot within the historic district, from willing sellers, for fair market value. (They showed the most interest, however, in buildings that were unused and badly in need of repair.) [15]

|

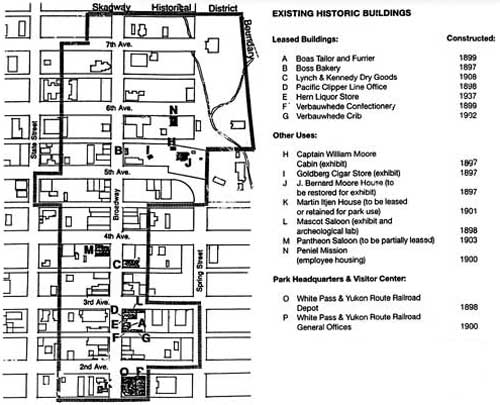

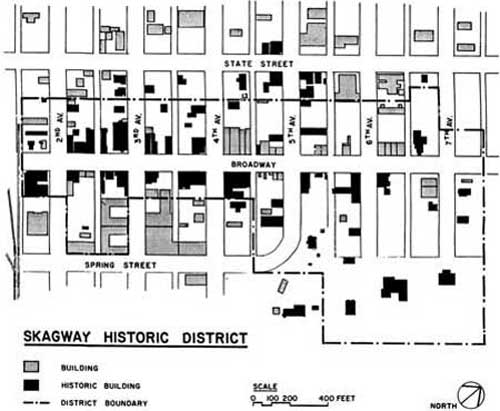

| Map 5. Buildings in the Skagway Historic District. Source: NPS, Design Guidelines for Skagway Historic District, 1981, 2. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Given that offer, some 45 landowners stepped forward and expressed a tentative interest in selling their properties. The first to finalize a deal with the agency was Marie Kallstrom. On July 25, she sold the Pantheon building, at Fourth and Broadway, and the adjacent vacant lot on Broadway (the former Rainier Hotel site) for $129,000. Two weeks later, Kallstrom sold another of her Broadway properties, the Lynch and Kennedy building (part of the Pack Train complex), for $45,000. In mid-September, the NPS acquired from Cy and May Coyne a third property, the vacant lot at the northwest corner of Broadway and Fifth Avenue, for $20,000; it did so in anticipation of moving a historic building to the site in the not-too-distant future. (As noted in Chapter 6, the Goldberg Cigar Store was moved to the site in August 1978.) And in late October 1977, the NPS finalized a deal with Malcolm and Mary Lou Moe, the owners of Moe's Frontier Bar. The Moes were willing to sell the Boss Bakery building, located across the alley from his tavern; they were not, however, willing to sell the lot on which it stood. The building was sold for $5,200. The purchase of most of these buildings had been contemplated as part of the 1973 master plan; the Pantheon building, however, had not been among them. [16]

Those who sold the various properties were no doubt pleased by the recent transactions, because the sale prices were substantially higher than private parties had previously been willing to pay. Public officials, however, began to worry about the potential effect of the sales on the tax base. In reaction, they pressured the NPS to authorize so-called payments in lieu of taxes. That pressure was eventually manifested in a cooperative agreement between the city and the NPS; the actions that led to that agreement are documented in the following chapter.

City officials, by now, began to worry about a federal takeover of the downtown historic district. To quell their fears, Superintendent Hoffman attended a series of city council meetings in the fall of 1977 and explained what the agency would and would not be doing in the community. By the end of November, Skagway Mayor Robert F. Messegee was able to report that "We all now have a much better appreciation of your methodology for planning and programming the development of the park. We welcome your offer to participate in similar meetings from time to time in order to keep the city advised of your progress." But city officials remained fearful. Superintendent Hoffman, in a December 1977 note, lamented that at a recent city council work session

They put it to us hot and heavy on our land acquisition program and its impact upon the city tax base. We were able to go over our program in sufficient detail to dispel the fears that we "were buying all of Broadway and kicking all the people out...." In general we feel very good about our relations with the city, and the hard data backs up our public relations efforts. [17]

Having cleared those hurdles, the agency continued its Skagway land purchasing program. On November 22, 1977, the NPS purchased the Peniel Mission property from John and Roberta Edwards for $65,500. Four weeks later, Jack and Georgette Kirmse sold three properties: Boas Tailor and Furrier, the Moore Tract (which included both the Moore House and the Moore Cabin), and the vacant lot between the Sweet Tooth Saloon and Dedman's Photo Shop. The three lots were sold for $66,809, $119,405, and $12,786, respectively. [18]

The agency purchased five additional Skagway properties in 1978. In late February 1978, the NPS purchased Verbauwhede's Confectionery, and the cribs behind it, from Malcolm and Mary Lou Moe for $30,000. In the late spring, it purchased a vacant lot on Broadway south of Second Avenue from the Longshoremen's Union for $28,100, where they intended to relocate the historic Martin Itjen house. Shortly afterwards, it bought the Itjen house (without the surrounding lot) from Jack and Marjorie Brown for $5,000. In September, Harold and Mavis Henricksen sold a large, vacant tract between Broadway and the Moore cabin for $75,000. The final purchase in the Skagway land acquisition program was completed in late December when Herbert and Georgina Riewe sold the Goldberg Building, again without the surrounding lot, to the NPS for $1,000. [19]

During the two and a half years since the park's authorization, NPS purchasing agents had bought significantly more properties in Skagway than the master plan had called for. They had made a total of 15 purchases: 8 with improved lots, 4 with unimproved lots, and 3 buildings which did not include the surrounding lots. (The agency had purchased ten parcels from private parties, instead of eight as called for in the master plan; three of the eight parcels that had been proposed for purchase in the plan had been bypassed.) The agency had purchased a total of 1.94 acres of land in downtown Skagway; for both the lots and the associated improvements, it had paid a total of $767,522.06. [20]

The agency also sought to purchase land in the Dyea area. Initially, it met with a cool reception from Dyea landowners. [21] Then, on June 27, 1978, it completed the purchase of the largest Dyea land parcel--335.89 acres--when it bought the old Pullen and Matthews homesteads from Mark R. Noyd and Mary L. Joseph for $646,000. The only remaining large parcel in Dyea was located north of the former Noyd-Joseph property. At one time, Wesley W. and Vivian R. Patterson had owned the entire 153.69-acre parcel which comprised the North Dyea area. During the 1960s and early 1970s, however, the couple had subdivided the homestead and had sold several small parcels to Skagway residents. On July 25, 1977, the Pattersons sold what remained of their homestead (83.12 acres) to the Park Service for $203,475. The agency also let it be known that they would buy back any of the other unimproved, privately-owned parcels in north Dyea. In response to that offer, three owners of 12-acre parcels agreed to sell in 1979 and 1980. The sellers were Wesley W. and Vivian R. Patterson; Wesley C. Patterson; and David and Bondy Logan. The parcels sold for $36,000, $50,000, and $52,000, respectively. [22]

In late 1980, the NPS acquired two additional land parcels. On November 26, the NPS acquired 1,690 acres of land which the U.S. Forest Service had previously managed in the White Pass Unit, east of the White Pass Fork of the Skagway River. Shortly afterward, on December 17, the agency purchased 0.34 acres of improved land in Skagway at 14th Avenue and Main Street (outside of the historic district) for use as an administrative site. The sellers, who had a trailer, a shed, and a garage on the property, were Lawrence and Mary Pagnac; the purchase price was $80,000. [23]

By the end of 1980, the agency had completed its initial land purchases. It had bought a total of 2.28 acres in Skagway for $847,522.06. (Within the Skagway historic district, 1.92 acres had been purchased.) In the Dyea area, it had purchased 455.01 acres of land for $987,475.00. In the Chilkoot Trail and White Pass units, Federal agencies (namely, the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management) had transferred to the park an additional 1,886.87 acres at no cost. Altogether, the agency had acquired 2,357.29 acres, which was just 17.7% of the 13,291 acres which Congress had included within the park's boundaries. (The State of Alaska held most of the remaining acreage, because it owned almost all of the Chilkoot Trail corridor and approximately half of the White Pass unit.) The total cost that the NPS had paid for the land and associated improvements had been $1,834,997.06. Congress, in Section 4 of its implementing legislation, had granted the agency $2,665,000 "for the acquisition of lands and interests in lands...." The price paid thus far for its Skagway properties was more than $800,000 under the Congressional ceiling. [24]

By 1980, NPS leaders felt that the land acquisition program had proceeded to the point that they were ready to formally establish Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Section 2 of Public Law 94-323 noted that the Secretary of the Interior would establish the park "at such time as he deems sufficient lands, waters, and interests therein have been acquired for administration in accordance with the purposes of this Act." On May 7, 1980, Interior Secretary Cecil D. Andrus declared that the park would be established as of May 14. A Federal Register announcement and an accompanying press release, both signed by Acting NPS Director Ira J. Hutchison, noted that "legal establishment is a step taken by the government to signify that the majority of the authorized property has been acquired for the park's historic resources. Establishment of this park assures the protection of a unique part of our history." [25]

NPS officials, who ideally sought to obtain title to all of the park's lands, were not able to obtain two major properties located within the new park boundaries. Both of these properties were owned or selected by the State of Alaska. The larger parcel constituted most of the Chilkoot Trail corridor. This parcel, 8,570 acres in extent, comprised over 64 percent of the land within Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park; it stretched from Long Wharf, south of Dyea, to the Canadian border. (As noted in chapters 3 and 4, the land was owned by the Bureau of Land Management, but the State of Alaska had selected the Taiya Valley lands in June 1961 and they had received de facto ownership of them in June 1974.) The NPS had been managing the state's interests in this area since August 1972, when the two parties had signed a cooperative agreement for the Chilkoot Trail. (A third signatory to the agreement was the BLM, which owned the state-selected lands in the Chilkoot Trail corridor. The BLM also owned a small parcel of non-selected land west of Chilkoot Pass.) The NPS hoped to acquire the Chilkoot parcel in order to ensure the protection of area resources. The master plan, however, did not specify the need for acquisition, and the legislation authorizing the park demanded that the NPS could acquire state-owned lands only by donation. The state's Department of Natural Resources, for its part, was in no position to donate lands that it did not yet own. Based on those constraints, the NPS could do little except continue the status quo. On April 6, 1978, as noted in Chapter 8, the NPS and the Alaska DNR renewed their cooperative agreement for a three year period; the new agreement included Dyea and White Pass as well as the Chilkoot Trail. [26]

The other parcel, which was 1,630 acres in extent, comprised roughly the western half of the White Pass unit. Specifically, the state owned all of the land located west of the White Pass Fork north of White Pass City, and all land west of the Skagway River south of White Pass City. The NPS, at first, had no cooperative agreement to manage these lands, as they had in the Chilkoot Trail unit, and due to the lack of recreational usage in the White Pass area neither the NPS nor the state showed much interest in the area. The state, however, was no more willing to donate to the NPS its White Pass parcel than its Chilkoot Trail lands, and as noted above, the White Pass was included in the expanded cooperative agreement worked out in 1978 between the NPS and the state's Department of Natural Resources. [27]

The NPS was also unable to purchase several properties in the Skagway Historic District in which it had shown an interest. The 1973 master plan, as noted above, had called for the purchase of the Idaho Saloon, Principal Barber, Verbauwhede's Confectionery, the Pack Train complex, Boas Tailor and Furrier, the Moore Cabin, and two other buildings (in addition to the depot complex and the Mascot Saloon complex, which were already owned by the National Park Foundation). As noted above, this "wish list" of properties changed significantly between 1973 and 1977-78, when regional lands division staff carried out their purchasing program. As it turned out, the only properties on the 1973 "wish list" that were actually purchased were Verbauwhede's Confectionery, Boas Tailor and Furrier, the Moore Cabin, and the Lynch and Kennedy store (which was part of the Pack Train complex). Memoranda generated during the late 1970s suggest that NPS personnel were unable to come to terms on only two properties--the Pack Train Inn and the Pullen House--in which they had shown an interest. The details surrounding the purchase negotiation, and later developments, are outlined in Chapter 7.

Three other major activities took place during the late 1970s. First, the administration of the three Alaska park units was formally severed from the Seattle unit. Soon after Congress authorized the park, an interim prospectus was drawn up which suggested that the park would be run as a single unit and managed by just one superintendent. Regional Director Russell Dickenson, however, recognized that "it will be not be practical, for the time being, to have the Seattle Unit...managed by the Superintendent ... in Skagway." Because of the "unusual situation" brought on by the 900 miles separating Skagway from Seattle, the Pioneer Square facility would be managed by the Pacific Northwest Regional Office. [28]

By October 1977, new superintendent Richard Hoffman began to argue that the time had come for Klondike Gold Rush to be managed as a single, comprehensive park. [29] Some regional officials, including Assistant Regional Director Temple A. Reynolds, supported Hoffman's position and urged that the regional office divest itself of direct responsibility over the local park unit. Regional Director Russell Dickenson and Deputy Regional Director Edward J. Kurtz, however, thought otherwise; consequently, the regional office made no moves to relinquish management control. [30] Management of the two units, therefore, continued to be separate. Hoffman soon recognized that the Seattle unit would become "the play thing of the Division of Interpretation of the Regional Office," and he demanded that the two Klondike units be formally split. Such a move, however, was not immediately forthcoming. Until 1979, most Klondike park documents pertained to both the Alaska and Seattle units; since then, however, the paper stream of the two park units has been almost entirely separate. [31]

A second major activity witnessed during the late 1970s was a slow, steady increase in staff. In July 1978, Jay E. Cable was hired as the park's first Chief Ranger. Cable arrived in Skagway after having served as a ranger at Capital Reef National Park, Utah and Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky. Cable was destined to work at the park for the almost thirteen years--until June 1991--far longer than any of the other new staff. [32] Robert Spude, a graduate student at the University of Illinois, began work that June as a historian with the University of Alaska's Cooperative Park Studies Unit. He was hired on a six-month contract to research the history of the various NPS buildings in Skagway, and the major structures in the Chilkoot and White Pass corridors; he was also asked to set up the park's library and photograph collection. His superiors, however, found his work exemplary and his contract was extended until December 1979. [33]

A third aspect of park activities during the late 1970s was an attempt to compile park planning documents. This was accomplished even though the park was new and staff levels were low. Planning documents written during the late 1970s, primarily by Superintendent Hoffman, included the Outline for Planning Requirements, completed by the regional office staff in mid-1977, and the Statement for Management, which was approved by regional officials in October 1978. (The latter document was largely finalized in November 1977; however, its publication and distribution was delayed because of the sensitive political situation surrounding the Alaska Lands Act.) The documents pertained to both the Seattle and the Alaska units; most of the enclosed verbiage, however, described conditions in Skagway and vicinity. In addition, Hoffman wrote a draft Dyea management plan (see Chapter 8); that plan, however, was rejected by Alaska Area Office staff and was never implemented. [34]

On the Canadian side of Chilkoot Pass, officials attempted (but failed) to advance the park planning process. As noted in Chapter 4, Canada's Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Jean Chrétien, had signed an agreement in principle with Jack Radford, British Columbia's Minister of Recreation and Conservation. That agreement, consummated in June 1973, provided for the eventual transfer of some 80 square miles from the province to the federal government and allowed that parcel to become a National Historic Park. In order to transfer the parcel, however, the B.C. parliament in Victoria had to act. During the summer of 1977 Radford's successor, Sam Bawlf, introduced a measure in the legislative assembly that would have effected that transfer. The measure was evidently given serious consideration; that fall, Gary Higgins declared that "Parks Canada anticipates Klondike will receive official designation as a national park in the near future," and as late as January 1978, the editor of Skagway's North Wind noted that "we are unofficially informed that the province of British Columbia has taken a step towards cooperating in this permanent Klondike Gold Rush Historical Effort." [35] Bawlf's bill, however, was not enacted and legislative matters remained at a standstill. Meanwhile, the management of the Chilkoot Trail continued as it had since 1974; the trail was managed from a headquarters in Whitehorse, and summer field patrols were operated from the remote campsite located at historic Lindeman City.

The Richard Sims Superintendency

On August 2, 1979, Superintendent Richard Hoffman announced to a meeting of the Skagway City Council that he was leaving his post (and was also resigning from the city's Planning and Zoning Commission). He said at the time that he was "very sad about leaving Skagway" and that the move was not his choice. His tenure, to be sure, had been a rocky one, and at various times he had clashed with his staff as well as with regional officials. He noted with pride, however, that he had accomplished his main job: buying buildings, starting programs and getting the park in motion. Hoffman was transferred to the Pacific Northwest Regional Office, where he became the region's Environmental Protection Specialist and Public Involvement Coordinator. [36]

Replacing him in Skagway was Richard H. Sims, who obtained the job by switching positions with Hoffman. Sims' appointment was announced in mid-August; three weeks later he visited Skagway and hiked the Chilkoot Trail. He assumed his new duties on September 24. [37]

Sims, a 26-year veteran of the National Park Service, had begun his career as a ranger at Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska. After serving stints as a ranger at Badlands National Monument, South Dakota and Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, he became a superintendent--first at Oregon Caves National Monument, and later at Crater Lake National Park. [38]

Soon after Sims assumed his post, new staff began to arrive. By the end of the year, the park had hired its first Interpretive Specialist, Dave Cohen, and the following year Amy Caldwell became the park's first administrative secretary. Both were experienced NPS hands; Cohen had worked in Anchorage on the so-called "d-2" issue and was currently working for the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, and Caldwell had served in a seasonal capacity for several years on the north rim at Grand Canyon National Park. Caldwell later married Andy Robertson, a member of the park's trail crew. [39]

Others came in to replace employees who had completed their service at the park. In 1980, Emily Olson began serving as an administrative technician in Barbara Montgomery's former position. In late April, David Snow began work as Alaska's first Area (later Regional) Historical Architect; in so doing, he carried on many of the same duties which Gary Higgins and Pete Bathurst had formerly undertaken. (Higgins, the previous architect, had left in April 1979, while Bathurst, a preservation specialist, had exited in January 1980.) And in April 1982, Eugene Ervine began work as an exhibit specialist. [40]

Additional new employees were added to the workforce during the mid-1980s. In March 1983, the park gained its first maintenance foreman, John B. Warder, Jr., who moved to Skagway after a long career at Olympic National Park in Washington. A month later, the park gained a new Interpretive Specialist when it hired Betsy Duncan-Clark. Ms. Duncan-Clark, who replaced David Cohen, had previously worked for the NPS at Herbert Hoover National Historic Site, Iowa, and Johnstown Flood National Memorial, Pennsylvania. In February 1984, Andrew Beierly was added to the park staff as a maintenance man. Beierly, a local hire, was a longtime Skagway resident and railroad worker. Beierly, Duncan-Clark, and Warder became the backbone of the Skagway workforce, because all three served on the Klondike staff for more than a decade. [41]

By 1983, six permanent personnel composed the Klondike staff, a number that increased to seven when Beierly commenced work in 1984. The permanent staff level, however, belied the size of the NPS labor force. Each summer, for example, brought seasonal crews of trail rangers, Skagway-area interpreters, and (beginning in 1980) Chilkoot Trail maintenance workers. In addition, the ongoing restoration efforts of the Skagway historical buildings demanded the employment of carpenters, laborers, and ancillary personnel. As a result, the number of seasonal employees reached as high as 30 individuals at a time. [42]

Park personnel tried, but failed, to hire local residents on park projects during this period. In 1980, and again in 1981, the NPS announced its intention to sponsor a 10-member Youth Conservation Corps group for the summer. Intended for high school workers (those aged 15 to 18 years old), corps members would have worked on the Chilkoot Trail, on the Dewey Lake trails, and at the Gold Rush Cemetery. Because of high prevailing wage levels, however, the NPS was unable to attract youth interested in working in the low-wage YCC positions. [43]

The park's operations budget reflected the relatively high staffing levels. During fiscal year 1980, when the Alaska units began operating with a budget separate from the Seattle unit, $558,800 was allotted for park operations. That figure rose by more than 35 percent, to $768,400, by fiscal year 1983. For the remainder of the decade, however, park budgets declined as often as they rose, and by 1989 the operating budget stood at $792,700, just 3.1 percent higher than it had been six years earlier. [44]

Two early employees later moved to the Alaska Regional Office (ARO), in Anchorage, where they continued to influence park policy. Robert Spude, who had worked on a park contract between June 1978 and December 1979, later worked for the BLM and the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service (both in Anchorage) before returning to the NPS in 1981. (Two years later, he became ARO's Regional Historian.) Dave Snow, when appointed to his Klondike position, became the Alaska Area Office (later Alaska Regional Office) Historical Architect. During his tenure in Skagway, Snow worked primarily on the restoration of the depot complex and other Klondike assignments. After his 1984 departure to Anchorage his work load diversified, but Klondike projects continued to comprise a significant portion of his work load.

One of the major events of the Sims superintendency was the completion of the park's reconstruction of the White Pass and Yukon Route depot and administration building. As explained more fully in chapters 4 and 6, the depot's restoration process had begun with Laurin Huffman's roof stabilization efforts in 1975, and large-scale efforts had begun when the building was jacked up and archeological surveys were undertaken in 1979. The restoration process was completed in early 1984. Soon afterward, park officials moved their offices from rented space on Broadway near Fourth Avenue to the new building. The visitor center was opened to the public in May, and the depot dedication took place on July 1. [45]

Relatively few planning documents were completed during Sims' tenure as chief. The park's first Statement for Management, which was prepared in 1978 and included both the Seattle and Skagway-area units, was revised in 1981 and tailored to conditions in and around Skagway. Regional Director John E. Cook approved the document on September 9, 1981. Three years later, on May 7, 1984, Sims issued an updated version. [46] Park staff also compiled a resource management plan. After two years of effort, a draft version was completed in February 1982. That plan, however, was criticized by various regional officials, and after two years of discussions the document was quietly tabled. [47]

After more than six years at the Klondike helm and 33 years of government service, Sims retired on November 30, 1985. Sims was proud of what he had accomplished during that period, particularly in the work completed on the various building restoration projects in Skagway. He was quick to admit, however, that the management of an urban historical park was more challenging than his previous assignments in natural resource parks had been--"at times more challenging than I would have preferred...." The local newspaper editor, Jeff Brady, gave him a large part of the credit for improving local relationships for the park when he editorialized,

When Sims came to Skagway, many townspeople were still having second thoughts about having let the park service in here. For a long time, it was tough being a "parkie." But as Sims leaves his post this month, many will thank him for what the park has done during his tenure, and what it has not done.

Park staff, in recognition of his efforts, held an open house on November 15 in which he and his wife Phyllis were honored guests. A large crowd attended. [48]

Clay Alderson Takes Over

After Sims' departure, Chief Ranger Jay E. Cable served as the park's acting superintendent. Cable led the park through the 1986 summer season. Then, in mid-August 1986, NPS Regional Director Boyd Evison announced the appointment of Russell C. (Clay) Alderson as the park's third superintendent. Alderson, who arrived in Skagway over Labor Day weekend, had been working for the agency since the late 1950s. He had served seasonal stints as a laborer and trail crew foreman at Grand Teton National Park. After working in the Kansas state park system, he worked as a trails foreman at Grand Teton until he was chosen, in 1975, as the first superintendent at Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site near Stanton, North Dakota. He remained there until 1979, when he left to fill the superintendency at Cedar Breaks National Monument near Cedar City, Utah. That position, which also grew to include administration over the Kolob Canyon portion of Zion National Park, occupied him until he moved to Skagway. [49]

Under Alderson's direction, further increases in the permanent staff have taken place. In March 1987, the new position of Cultural Resource Specialist was created and filled by Karl Gurcke, a historical archeologist who had been working for the park on a seasonal basis since 1984. During the off-season, he had previously been the assistant curator at the University of Idaho's Laboratory of Anthropology. That summer, the park was busier than it had ever been; at one point it had a work force of 43, of which 21 were local hires. [50] In 1988, a new half-time position for procurement clerk and a new half-time administrative assistant were created. The former was filled by Evelyn Meyer, the latter by Niki Hahn, both of whom hailed from Skagway. In 1990, the park created a new subject-to-furlough park ranger position. The individual selected, Jeff Mow, became the lead Chilkoot Trail ranger during the summertime and assisted the Chief Ranger during the off-season. [51]

In 1991, the park hired its first full-time painter, George Barratt; the same year, Debra Sanders became Klondike's first full-time museum specialist. [52] A final selection made that year was Mike Colyer as project construction supervisor. Colyer, a longtime Skagway resident and former railroad worker, had begun working on the park's preservation crew in the mid-1980s; then, in 1988, he moved to Williamsport, Maryland, where he attended the agency's Williamsport Preservation Training Center. The park had had several construction supervisors after Regional Historical Architect Dave Snow left for Anchorage in 1984; only one of those men, historical architect Ray Todd, had remained in his position for more than a year. Alderson expressed confidence that Colyer "gives us the continuity of leadership that this project has not had since it was started." [53]

The following January, Bruce Reed began work as the new Chief of Interpretation and Resource Management. Reed, who hailed from Guadalupe Mountains National Park in Texas, replaced Jay Cable, who had vacated his position the previous July. Later that year, Doreen Cooper began work as the park's first project archeologist; her position, funded by the agency's Denver Service Center, continued the work which Cathy Blee, Marianne Musitelli, and other DSC archeologists had carried on for more than a decade. The number of seasonal workers during this period, as before, remained high. In 1988, for example, 38 employees were on board during the busiest summer months, 17 of which lived year-round in Skagway or Dyea. [54]

The park's budget has reflected the recent increase in staff. During the middle to late 1980s, as noted above, the park's operating (ONPS) budget consistently hovered between $725,000 and $800,000. In 1990, however, the budget rose 7.7 percent to $854,000, and in 1991, it rose another 34 percent to $1.14 million. The ONPS budget has continued to increase since 1991; as of 1995, it stood at $1.36 million.

Alderson has been the superintendent since 1986 and remains in that position. He has, however, taken two remote assignments during his tenure. In May 1991, he moved to McCarthy, Alaska and spent the next five months coordinating structure engineering and environmental surveys of the Kennicott mill property, which the agency was proposing to purchase. Thereafter, Jay Cable served as Acting Superintendent. Cable, however, accepted a position as the Regional Safety Officer and moved to Anchorage in July. In his stead, Dave Mills (from the Northwest Alaska Office in Kotzebue) replaced Cable as Acting Superintendent for the next three months. Two years later, Alderson was detailed to Anchorage and spent five months working as a special assistant in the Alaska Regional Office. (He had been hired to be the state coordinator for President Clinton's "Rebuild America" jobs program. The bill authorizing that program, however, ran into a Republican-led filibuster and did not become law.) Janet McCabe, a longtime special assistant in Anchorage, took Alderson's place in Skagway and became acting superintendent. [55]

Parkwide Planning Efforts

Soon after his arrival at the park, Alderson realized that little planning had taken place in the past several years. In order to update action plans for the park, he and his staff prepared a Statement for Management. A draft copy was completed by the end of 1987, and by the end of 1988 the regional office had granted its approval to the final report. [56] Alderson also attempted to complete the writing of the Resource Management Plan, a draft version of which had been completed during the early 1980s. Public scoping sessions on the RMP were held in 1989 and writing began in 1990, but staff shortages prevented the document from being completed. [57]

During the same period in which activity was taking place on both the Statement for Management and the Resource Management Plan, Superintendent Alderson raised the idea of writing a park General Management Plan (GMP). No master plan had been written in the 13 years since the park had been created; the only previous plan was dated May 1973. (It had been nominally updated in September 1976, in response to the passage of the park bill.) The park, moreover, was one of only two Alaska units without an updated general management plan; all the other units except Sitka had undergone a planning process during the mid-1980s. In order to correct that deficiency, the regional office's Division of Planning made an effort in late 1989 to come up with some of the funding necessary to initiate the process. [58] Then, in 1990, it gave the park a small sum to initiate the scoping process. The Washington office and the Denver Service Center were notified of the need for a new plan. By the end of the year, DSC had pledged $125,000 to prepare a Development Concept Plan for Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail. The Washington headquarters, however, refused to release funds for the preparation of a GMP. [59]

The scoping process finally began in 1991. Public meetings were held that spring in Skagway, Anchorage, Whitehorse, Haines, Juneau, and Seattle seeking public comments on what the GMP should address. NPS officials also held a meeting with their Canadian Parks Service counterparts, looking for their input during the early stages of the planning process. [60]

The agency digested the comments made at the scoping meetings and in mid-May 1992, it made public its intention to prepare a general management plan and accompanying environmental statement. A month later, it held a series of meetings in which it endeavored to familiarize the public with park management, to ask its ideas about future management, and to offer the public a choice of park management options. [61]

Meetings were held in six cities in Alaska, Washington and Yukon Territory. The most lively discussion, however, took place at Skagway's city hall on June 22. Despite the flurry of summertime activity, fifteen local residents attended and gave planners a passel of suggestions, most of which related to access and interpretation in the Chilkoot Trail and White Pass Trail units. Planners at the meeting promised to respond to those suggestions and have draft plan alternatives ready for public comment by the year's end, followed by the preparation of a draft general management plan and EIS in 1993. [62]

Agency planners were delayed in their response to the public comments, but in mid-June 1993 they distributed a series of three preliminary management alternatives. Based on the degree of development desired, these included a "no change" alternative, a plan that called for a modest facilities increase, and a plan calling for a substantial facilities increase. The agency held another series of public meetings, and Janet McCabe, the acting superintendent, asked the city for its reaction. [63] The city, in response, held a July 21 hearing on the matter, and for two hours local citizens provided comments, many asking the NPS to keep additional facilities investments to a minimum. The city council, as a result, tentatively decided to pass a "no change" resolution. McCabe, however, prevailed on the council to delay the vote on its resolution until the next meeting. During the intervening period, she was successful in revising the council's original language. The final resolution, passed on August 6, asked the NPS to take "a conservative approach" to development; it asked for the agency to adopt a "no change" alternative, with modifications. [64]

The plan was then entrusted to the regional office for the preparation of the draft GMP and EIS. Work on the document began during the fall of 1993. [65] A series of delays by regional personnel, however, postponed the publication of the draft document for more than a year, and the Draft General Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement for the park was not released to the public for comments until June 1996.

The other major park plan pursued in recent years has been the Resource Management Plan. The RMP, as noted above, had been written in draft form in the early 1980s but had never been completed. When Karl Gurcke was hired as a resource management specialist in the spring of 1987, it had been hoped that one of his first responsibilities would be the completion of an RMP. The Scope of Collections Statement, which Gurcke wrote in March 1988, noted that the RMP was "currently being rewritten." He was able to make little progress, however, until Bruce Reed became the Chief Ranger in January 1992. [66] Reed decided to split project work into two areas; he would write those sections pertaining to natural resources, while Gurcke would write about the park's cultural resources. The two men completed a rough draft of their respective sections in December 1993 and submitted the plan to the regional office. The plan was considered acceptable but for a few minor modifications, and the park submitted a revised plan in the fall of 1994. The final plan was signed by Acting Regional Director Paul Anderson on December 15, 1994.

|

| The park's first (1977) group of seasonal interpreters and rangers posed at the old White Pass depot, which served as the park's visitor center that year. Richard Hoffman, the park's first superintendent, is seen at left. To his left are Russell Plaeger, Meg Jensen, John Jackson, Janet Ross, Craig Juleen, and Linda Chesney. Ross and Jensen were Chilkoot Trail rangers; the other four were Skagway interpreters. The dog was named Rolfo. (John Jackson Collection) |

|

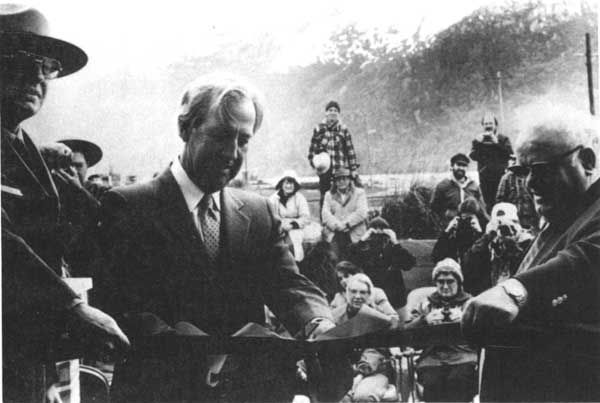

| (top) Richard Sims was the park's second superintendent; he served from 1979 through 1985. He is shown here, at left, at the July 1984 visitor center dedication with NPS Director Russell Dickenson (center) and WP&YR official Marvin Taylor. (bottom) Clay Alderson is the park's current superintendent. This photo was taken in September 1986, shortly after his arrival in Skagway. (Skagway News, July 4, 1984, 1 (top) and September 17, 1986, 3 (bottom) ) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000