|

KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH

Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park |

|

| PART I: THE MAKING OF THE PARK |

Chapter 4:

Authorizing the Park

The International Park Proposal

As noted in Chapter 3, Alaska corrections personnel opened up the U.S. side of the trail in 1961-64, and by the winter of 1967-68, both state and NPS officials were aware that a park proposal was in the works. Canadian officials, during this period, watched the ongoing activities with an increasing degree of interest.

They had little knowledge of the Chilkoot, however; the only Chilkoot trips yet taken by Canadian officials had been James Lotz's hikes in 1963 and 1965 and a 1967 reconnaissance by Yukon Corrections officials.

In order to spur interest in the trail by officials from both sides of the border, Canada's National Historic Sites Service (NHSS) chief Peter Bennett, in April 1968, proposed an international Chilkoot hike. Such a hike would take place late that summer and would include representatives from a wide variety of agencies that had an interest in the Chilkoot Trail. The purpose of such a hike would be to discuss the trail's desirability as an international trail. [1]

Because of the impending Skagway Alternatives Study and the crisis over the Skagway railroad depot, the proposed hike had to be delayed. [2] By the following summer, however, the alternatives study had been completed, and a joint, late-season hike was planned.

The long-anticipated event was held over Labor Day weekend, 1969. Seventeen hikers participated in the four-day event. The state of Alaska was represented by Mike Leach from the Division of Lands. NPS representatives included Robert E. Howe, the Superintendent of Glacier Bay and Sitka national monuments, and Ted Swem, the Washington-based Assistant Director for Cooperative Activities. The Interior Department was represented by Yvonne Esbensen, a assistant to Secretary Hickel. Yukon Territory representatives included Ron Hodgkinson, the Assistant Commissioner, and both Victor Ogison and Gary McLaughlin of the territory's Corrections Department. The National and Historic Parks Branch was represented by Peter Bennett, Director of Historic Sites in Ottawa; Don Cline, an Ottawa-based planner; Gordon Gilroy, the Assistant Regional Historic Sites Director in Calgary; and Bruce Harvey, the NHS representative in Whitehorse. Several Skagway residents also made the trip. They included Mayor Edward Hanousek, Chamber of Commerce President (and local banker) Ed Leon, and packer Dave Hunz. [3]

Officials from the two countries had organized the Chilkoot hike as part of a larger effort to publicize the historic resources along the entire gold rush corridor. Participants, therefore, followed the hike by taking the train from Bennett north to Whitehorse; they then flew to Dawson and spent a day examining that area before returning to Whitehorse to evaluate what they had seen during the previous week's activities. On September 4, Swem and Bennett jointly produced a confidential report which outlined their proposal for an international historic park based on the Klondike Gold Rush theme. [4]

The hike and its aftermath were successful by all accounts. Director Hartzog, who received a copy of the joint report, noted in a memorandum to Interior Secretary Walter Hickel that

it greatly stimulated interest in the need to conserve the historic and scenic values of the entire Gold Rush route starting at Skagway and terminating at the gold fields near Dawson in the Yukon. The Canadian Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development officials and the National Park Service enthusiastically endorsed not only their own respective historical preservation proposals, but also the concept of an international historical park. [5]

Less than a month after the hike took place, Ted Swem met with Merrill Mattes in Washington and gained more background on the Skagway National Historical Park/ Klondike Gold Rush International Trail proposal. By early November, Northwest District Director Rutter had officially approved the concept, and Swem had gained the Director's approval for the new park, to be called Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. [6] Hartzog, in turn, recommended the park's establishment to Interior Secretary Hickel. That park was to include

a historic district in Skagway, a small area at Dyea, including reconstruction of three buildings [a barn, store, and house] at the old townsite, and sufficient lands along both the Chilkoot and White Pass Trails to allow public use and facility development and to protect adequately the historic and natural scene. [7]

The Canadians were likewise active. On November 11, 1969, the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Jean Chrétien, flew to Whitehorse. Before a crowd at the Chamber of Commerce, he announced the creation of new national historic sites at Dawson City (where four buildings were to be designated) as well as at Bonanza Creek, Whitehorse, and Bennett. He also unveiled a $2 million development package designed to assist in site restoration. Along the Chilkoot, the Canadians planned to stabilize the Bennett church and construct a historical interpretation center. [8] Beyond that, they hoped to coordinate their Chilkoot Trail development activities with those on the U.S. side. Hartzog, for instance, recommended the implementation of a series of measures, all of which had been agreed to by Swem and Bennett in September. The NPS director suggested

that a standard sign and marking system be used on both sides to reflect a unity in approach and the true international aspect of the project, that we issue joint maps and publications covering the Gold Rush story, and that we cooperate in interpreting the story of the Gold Rush.... Also, we would hope to move ahead to establish certain stretches of the Upper Yukon River in Canada and the United States as a historic riverway as a part of the Klondike package.

To help achieve this coordinated effort, we recommend the appointment of an international advisory committee made up of representatives of all levels of government involved, plus outsiders, to advise on implementation of this proposal, and also a steering committee comprised of representatives of the park agencies from both countries. We believe the legislation on our side and any official action on the Canadian side should recognize this as a truly international park, even though each country would be responsible for development and operation of its own park units. [9]

Hickel, who because of his Alaska background had a personal interest in the proposal, approved of Hartzog's recommendations on December 16. [10] Two weeks later, Hickel and Canada's Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Jean Chrétien, simultaneously issued press releases announcing an international historical park, based on the Klondike Gold Rush theme, which would include sites in Alaska, British Columbia, and the Yukon. Chrétien's announcement noted that

A significant feature of the proposed Klondike Gold Rush International Historic Park will be the joint development and interpretation by both countries of the historic Chilkoot and White Pass Trails from Dyea and Skagway to Bennett. Also under study is the establishment of a Yukon Historic Waterway, embracing the water route to Dawson City and designed to preserve the historical environment of its more significant features. [11]

The Canadians also announced plans for a historic preservation program in the Yukon, while the Americans recommended that Congress establish a Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. [12]

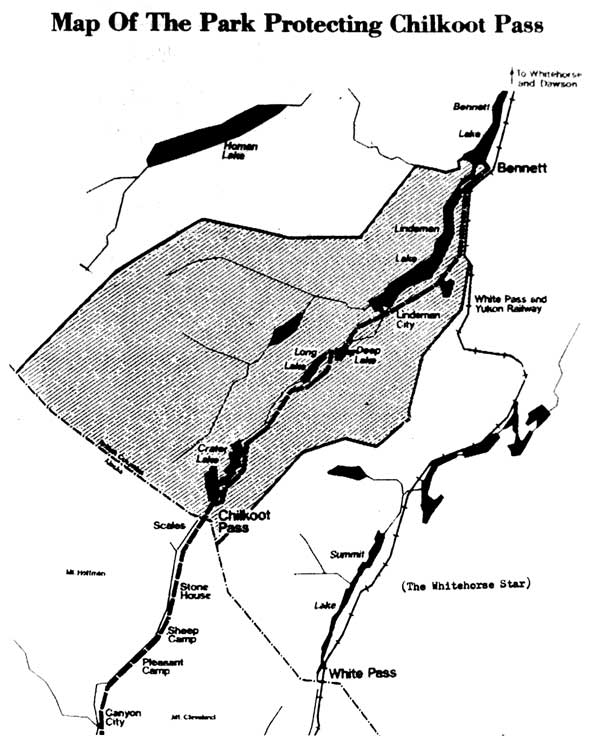

The Park Master Plan

Following the December 30 announcement, officials of both countries began to prepare more specific land management proposals. Several months later, Canada's National Historic Sites Service issued a document entitled Klondike International Historic Park: Provisional Development Plan. That plan, which reflected the concerns of both U.S. and Canadian authorities, called for the "protection of the unspoiled and remarkable historic and scenic attractions of both [the U.S. and Canadian] Trails by the acquisition of land from skyline to skyline on the Chilkoot Trail from Skagway to Bennett." At Bennett, it proposed that the NHSS stabilize, preserve and fence the Presbyterian church, and acquire two or three railway cars "to establish exhibits featuring the story of transportation to the Yukon." The plan also called for a directional and historic marking system from Skagway to Dawson, the restoration of the S.S. Klondike at Whitehorse, and a broad plan of improvements along the Yukon River and in the Dawson area. The plan recommended that a consulting company be chosen to write a provisional master plan study for the Chilkoot Trail. [13]

On the U.S. side, the NPS began to prepare a park master plan. (A master plan was necessary before any bill establishing a new park unit could be submitted to Congress.) Crucial to the success of the park proposal was the support of the State of Alaska, the City of Skagway, and the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad. In January 22, 1970, therefore, the NPS's Ted Swem began that effort. He met in Washington with Alaska Department of Natural Resources Commissioner Thomas Kelly, who was primarily concerned with the management of the Chilkoot Trail corridor. Swem told him that the NPS

would like basic responsibility for administration of the Chilkoot and White Pass Trails, Dyea, and a Historic District in Skagway, but that if the State didn't feel that it could give up the State selected lands involved right now, that we might be able to work out [a cooperative agreement]. I told him, however, that because of the international scope of the historic story, and the varied nature of the resources involved, I thought the Federal government was probably in a better position to handle this project than the State. He said he agreed and wouldn't mind working out some arrangement like this, providing that they could make up for the loss of these selected lands by being able to select other public lands that they desired.... I asked whether he was agreeable to pushing for revocation of the [1948] water withdrawal on the Taiya River and he said he would do anything possible to get rid of it; that he wanted no part of a water project in this location. [14]

By mid-February, Regional Director John Rutter had also been informed about the proposal, and on April 2 he flew to Juneau to ascertain a broad range of opinions from state officials. Rutter met with Tom Cantine of the Alaska State Power Commission, with the director of the state museum, and with two members of the Department of Economic Development (DED); he also had a second meeting with Tom Kelly of DNR. Rutter ran across few problems during those meetings; the DED personnel, in particular, were enthusiastic about the proposal. Both Cantine and Kelly, however, criticized the NPS's plans because they were unwilling to ignore the proposed Yukon-Taiya power project. Both were well aware of the Canadians' opposition and were likewise aware that little active planning had taken place in recent years. But Cantine was quick to note that "of all the State's [proposed] water power projects, the Yukon-Taiya Project offered the fewest problems from an engineering standpoint," and Kelly "wondered if a balance between water and historic projects could not be made." [15] Governor Keith Miller was skeptical that a historical trail and hydroelectric plant could co-exist in the same narrow valley. But Walter Hickel, who was Secretary of the Interior as well as Miller's predecessor, declared that "I do not think it is possible nor appropriate ... that one particular use is the highest and best for the area." "The Taiya River Valley," he noted, "might well permit both uses without any real diminishment in the value of either." [16]

NPS officials also travelled to Skagway. In March, they had preliminary discussions with Mayor Malcolm Moe and White Pass officials. Then, on May 15, 1970 they had a public meeting on the proposed park. The NPS officials in attendance, who included Bennett Gale and Rodger Pegues of the Pacific Northwest Regional Office, Bob Howe of Glacier Bay National Monument, and Ernest Borgman from the Alaska Group Office in Anchorage, were sensitive to local Chamber of Commerce concerns and promised that the proposed park "would not interfere with multiple use of [the local] area." [17] The city council, at the time, was split on the issue. Some on the council were in favor of the NPS's plans, both in town and in the Taiya Valley, but others were fearful that renovating Skagway's buildings would give the agency a foothold which might eventually tie up the Taiya Valley to further development. Some, attempting to compromise, wanted the city to request State Park status. But Ted Smith, head of the state's Division of Parks, replied that he would prefer to see the NPS take over the trail. [18]

It appeared that the only substantial difficulties which state and local officials had with the proposed park concerned the Yukon-Taiya project. In order to iron out those difficulties, Bennett Gale, the agency's Associate Regional Director in Seattle, flew to Juneau in mid-December 1970 and met with Gus Norwood, the head of the Alaska Power Administration. As a result of that meeting, the two decided that "with proper planning and management, the two proposals can be reasonably compatible." [19] Because the NPS had satisfied each of the state's major concerns, Governor William A. Egan, in a letter to Interior Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton, gave his enthusiastic support to the gold rush park idea. [20]

Crucial to the success of the NPS's efforts in the area would be the preparation of a report that would link the physical resources in the proposed park to the area's history, and assess that history in the context of nationwide historic themes. Edwin C. Bearss, a historian in the agency's Office of History and Historic Architecture, was assigned that task in mid-1969. That August, he travelled to the Skagway and Dyea areas and hiked over the Chilkoot and upper White Pass trails. Using a broad array of source material, Bearss compiled a historic resource study which included more than 300 pages of text and more than 80 maps and photographs. His study was released in November 1970. [21]

The preliminary working draft of the conceptual master plan was submitted to the Pacific Northwest Regional Director in January 1971. Two months later, he approved the document and submitted it to the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments. When the Advisory Board met in April 1971, its chairman noted that

it is considered appropriate...to recommend not only a national historical park, but a further step to join with Canada for an even more imaginative proposal, a Klondike Gold Rush International Historical Park. An integrated effort by the two countries to awaken a historical resource that has long been slumbering should not be delayed.

On May 6, the regional office released the document to the public and issued a press release announcing the proposed park plan. [22]

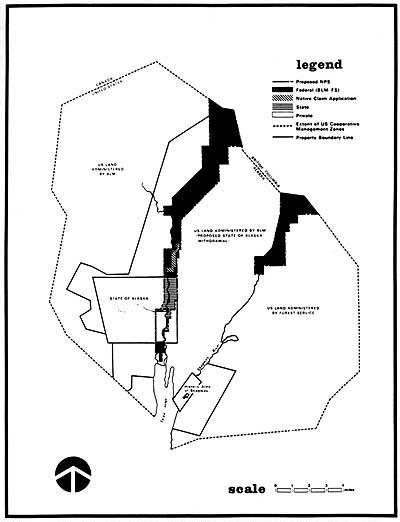

The plan adopted in the spring of 1971 was, in many ways, similar to Alternative Three which had been promulgated in March 1969 and approved that November by Regional Director Rutter. It still called for the establishment of a narrow historic district and the NPS acquisition of just three buildings: the depot complex, the Mascot complex, and Boas Tailor and Furrier. The proposed park, however, was to encompass 22,000 acres in and around Skagway--far larger than the 900-odd acres in the 1969 study. It called for the in-fee purchase of a mile-wide corridor for the entire length of both the Chilkoot and White Pass trails; in addition, it called for the protection, through cooperative agreements with the State of Alaska and the Forest Service, of the Taiya and Skagway river valleys from one topographic crest to the other. [23]

The plan also provided the park's first clear statement of purpose. The Alternatives Study was an ad hoc document which was intended to prevent the imminent destruction of Skagway's historical architecture. By March 1971, that threat had certainly not abated, and indeed, the preservation of the railroad depot was still by no means certain. The 1971 plan, however, put the preservation of Skagway's buildings squarely in the context of American gold rush history. It noted that

Although several mining communities in the Rocky Mountain West and Great Basin area of mainland United States are recognized as national landmarks, no area within the Park Service System has been singled out to illustrate a gold rush as part of our national heritage. No town in America offers a finer array of historic resources than Skagway for interpreting the story of a historic gold rush. The Klondike Stampede has all the dramatic ingredients necessary to create a magnificent historical and recreational park which transcends international boundaries. [24]

NPS officials distributed a large number of copies of the preliminary master plan, hoping to get as much feedback as possible on it. [25]

In order to collect public comment on the plan, an NPS master planning team from San Francisco headed up to Skagway. They held a public meeting on May 26 and remained in the area for a week. The public meeting revealed that the basic proposal propounded in the March report was far too vague. The plan, for instance, called for many specific improvements--from boardwalk improvements to building restoration to the installation of new railroad tracks--but it was categorically unspecific as to who would pay for them. Local citizens demanded answers, and the planning team could not immediately supply them. The state, while broadly supportive of the park concept, was worried that the provision of broad scenic protection to both river valleys would stifle area residential and industrial development. [26]

Local citizens were more vehement in their opposition to land use controls. The May 1971 plan, and the public meeting which followed the plan, was the first time in which Skagway's citizens had been confronted with a park which included the Skagway and Taiya river valleys within its boundaries. Many feared the loss of the recreational activities which they had long enjoyed. Longtime resident Joseph E. Herpst was so frustrated at the NPS's plans that he circulated a petition that was quickly signed by 166 local residents--over half of Skagway's registered voters. The petition said, in part:

We, the undersigned citizens of Skagway, Alaska, do not wish to have Skagway or the surrounding area made into a State or Federal Park that would have any restriction on any firearms, snow machines, trail bikes or restrict hunting in any way.... We surely do not want to be part of a Park that would have certain hours or seasons which the park can be used. Hunting, fishing, shooting, using snow machines and trail bikes are recreation for a lot of people in Skagway. Why must we give up our recreation so outsiders can walk in a park 3 months out of a year? [27]

Although local citizens felt that the government was interfering too much in the area's affairs, certain agency personnel came away convinced that a greater governmental presence was needed in order to preserve the area's history. Douglas Cornell, part of the NPS team, felt that Reed Jarvis's development plan, as laid out in the March 1971 Master Plan, offered too little NPS involvement. Cornell recommended that the agency take one of three new paths as it related to Skagway buildings management. At a minimum, Cornell recommended that the NPS purchase 24 lots in the Historic District and obtain one historic building (the city library) as part of those purchases. A second, stronger alternative called for the agency to acquire approximately ten additional buildings in the Historic District for restoration; these buildings would then be leased or sold back to the private sector for business use. [28] It also urged the NPS to pave the streets, repair the boardwalks, and replace street lighting with period fixtures. A third, even stronger alternative called for the acquisition of eleven more buildings than had been called for in the second alternative.

Cornell suggested other alterations to the March 1971 plan. The Historic District, for example, had to go beyond the boundaries which had been suggested in the 1969 alternatives study. (These were the boundaries that had originally been delineated in the city's 1964 community plan.) Areas to be added to the Historic District included the eastern extension of Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh avenues. He also recommended a stronger historic zoning ordinance, the establishment of a historic district commission, and an improved zoning ordinance. At Dyea, he suggested that a campground as well as a ranger station should be constructed. [29] Rod Pegues, who was the region's assistant director, agreed with Cornell's assessment, and noted that "I think we should shoot for a major project--including Seattle as well.... The significance and the potential visitation exists, and we ought to go after it." [30]

Before planners could proceed with the preparation of a revised master plan, they spent another week in the Skagway area. Their August visit featured a conference with personnel from the Canadian Environmental Services, Ltd. (CES, a Vancouver-based consulting company, had been selected to prepare a provisional master plan for the Canadian side of the Chilkoot Trail.) The NPS team also held a public meeting in Skagway and took part in a second internationally-sponsored Chilkoot Trail hike. More than 20 took part in the hike. The NPS planning team included Douglas Cornell, Bob Howe, Gerald Patten, and Rod Pegues, while the Canadian consulting team members included Rainer Fassler, Erik Karlsen, and Jack Shadbolt. Pierre Berton, the well-known author of Klondike, a popular gold rush history, was also on the team. Other Canadian participants included Bruce Harvey, V. P. "Sandy" Rolfson, and Peter Matrosovs, all from the National and Historic Parks Branch; Gary McLaughlin, from the Yukon Department of Corrections; Lee Munn, a tourism official from Ottawa, and T. R. Broadland, from British Columbia's Historic Parks and Sites Division. Other American officials included John Hall, U.S. Forest Service; Jack Tripp, Alaska Travel Division; and Michael Leach, Alaska Division of Lands. [31]

After returning from the field, the combined planning teams met in Skagway and Whitehorse. The NPS planners began to prepare a master plan which was modelled, to a large extent, on the ideas which Douglas Cornell had outlined in June. The agency still envisioned a 22,000-acre park composed of lands along the Chilkoot and White Pass trails as well as parcels in Skagway and Dyea. But major changes took place in Skagway and Dyea. In Dyea, 12 residences and recreational cabins were to be purchased, while in Skagway, park officials planned to purchase 25 commercial buildings as well as the library. Planners also proposed a unit in Seattle and the purchase of a single commercial building in the Pioneer Square area. Appraisers estimated that the cost of the park proposal would be approximately $2.4 million: $1.3 million for land purchases, $0.5 million for building improvements, and $0.6 million for administrative and other costs. [32]

The most dramatic changes in the new plan were felt in Skagway. The NPS planned to purchase, restore, and interpret fourteen buildings in the historic district. (These buildings included the Moore House and adjacent cabin, the three-building Pullen House Complex, the two-building depot complex, Boas Tailor, and the three-building Mascot Saloon complex.) The NPS also proposed to purchase and restore eleven other downtown buildings but to allow them to be used for private commercial purposes. (The eleven included the Idaho Saloon, the Lucci Grocery, the Principal Barber Shop, Verbauwhede's Confectionery, and the four-building Pack Train Saloon complex.) The Red Onion saloon was to be used as a living interpretive exhibit, jointly used by the NPS and a concessioner. The plan also called for three private commercial buildings and another three interpretive structures to be moved to the historic core from off-Broadway locations. [33]

By December 1971, a second draft of the master plan was reported to be nearly complete, and NPS planners were hopeful that it would be ready for public distribution in early 1972. [34] State officials, however, balked when they saw what had transpired since the issuance of the preliminary draft. They feared that the park would block any future efforts to construct and operate the Yukon-Taiya power project; the new park might also prevent the establishment of new port facilities near the mouth of the Taiya River. To address these concerns, the state proposed the preparation of an area land use plan. The NPS had no comment on the port proposal, but agreed with the state's objections regarding the Yukon-Taiya project and agreed to participate in the creation of the land use plan. Because of the conflict, the issuance of the revised draft was delayed until late June. [35]

After receiving comments from interested parties, a five-man international team (Don Campbell, Bob Howe, and Laurin Huffman of the NPS, with Bruce Harvey and Roman Fodchuk of Canada's National and Historic Parks Branch) once again travelled to the Skagway area and made a trip over Chilkoot Pass. They met at Lindeman Lake and discussed trail standards, artifact security, trail markers, signing, and similar measures. [36]

During the preparation period of the second master plan draft, NPS officials learned that Natives had applied for three land claims along the Chilkoot Trail. Andrew C. Mahle, a longtime Skagway resident, applied for a 160-acre allotment in the Sawmill-Finnegan's Point area in April 1971. His brothers, Fred and Harlan, had each applied for 80-acre allotments in the same area that October. The brothers claimed occupancy dating back to 1950, 1952, and 1961, respectively. Later that year, BLM surveyors visited the three claim sites and established corner posts. No one knew, at this point, whether the Mahles' claim would prove to be valid, but NPS officials recognized that they and the state of Alaska were not the only possible Taiya Valley landowners. [37]

By December 1972, the park proposal--this time, for a park not to exceed 12,000 acres--was declared to be complete. [38] Just before the plan was ready to be printed, however, Director Rutter had a change of heart and decided that the planned purchase of 26 of Skagway's historic structures was simply too great of a resource commitment. He reduced the building restoration program back to 16 buildings. Nine buildings were to be retained by the NPS for interpretive purposes: they included the two-building depot complex, Boas Tailor and Furrier, the three-building Mascot Complex, the Moore Cabin, the Boss Bakery, and the Tanner Building. The agency would purchase seven other buildings, then lease them to private commercial uses; these seven included Verbauwhede's Confectionery and its associated cribs, the four-building Pack Train complex, the Principal Barber, and the Idaho Saloon. [39]

The need to create new maps in response to Rutter's decision, and the vagaries of the printing process, delayed the publication of the final master plan until September 1973. Because of approval delays by the Interior Department in Washington, widespread distribution did not take place until February 1974. Chief among those who awaited its publication were Congressional leaders. Both senators and representatives had introduced a Klondike park bill in April 1973, but hearings on the bill could not take place until the master plan was completed. [40]

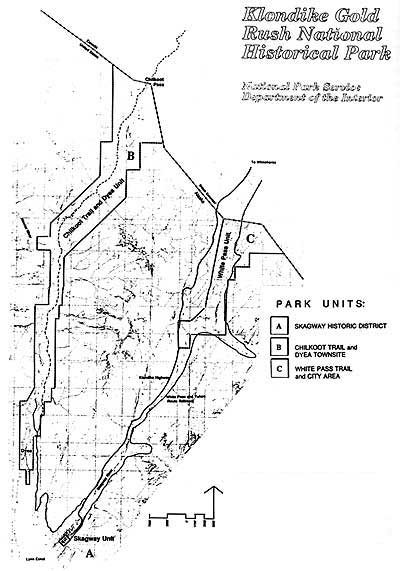

The master plan called for the creation of a park that, in many respects, resembles that seen today. The proposed park was to be not larger than 14,300 acres in extent and was to consist of four separate units: a Seattle interpretive unit, the Skagway historic district, a Chilkoot Trail unit, and a White Pass unit. In Skagway, the plan called for the depot buildings to be used as a visitor contact station; in addition, the historic district would be extended all the way to the railroad right-of-way between Fifth and Seventh avenues. Plans for Dyea called for the construction of a staffed interpretive center and trailhead contact station. For the Chilkoot Trail, the plan called for the scenic protection of the Taiya River valley, and the protection of historic trailside ruins. (It made no mention of the three Mahle claims.) For the White Pass unit, planners called for the scenic protection of the Skagway River valley and the protection of the ruins at White Pass City. [41]

Many ideas in the master plan, however, have not been fulfilled or were later seen as unrealistic. The plan, for example, proposed the installation of Engine #52 and a 70-class locomotive on Broadway; the creation of three off-Broadway parking lots; and an outdoor display area at Fifth Avenue and Broadway devoted to describing Skagway's function as an outfitting center. Planners also proposed that some of the NPS buildings along Broadway "would be restocked with vintage items and contain various historic exhibits," and that "NPS personnel would be dressed in Klondike period attire to recreate the sense of this gold rush town." Plans for Dyea called for the brushing of the historic street alignment and the establishment of two walk-in campgrounds. For the Chilkoot Trail, the plan called for the trail to be rerouted "to its true historic location, where feasible." For the White Pass unit, planners proposed the restoration of the upper portion of the White Pass Trail, a portion of the Brackett Wagon Road, and the construction of a connecting trail from the proposed Skagway-Carcross road to the park unit. [42]

A key difference between the preliminary (March 1971) working draft and the final (May 1973) master plan was the addition of a Seattle unit. Seattle was first suggested in May 1971, when Regional Director John Rutter asked Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman to comment on the plan. Rutter noted at the time that "we believe this proposal ties in quite closely with some of the concepts you are considering in your Pioneer Square and Seattle Waterfront Park Programs." (The Pioneer Square-Skid Road Historical District had been placed on the National Register of Historic Places less than a year before, on June 22, 1970.) Two weeks later, NPS officials sent copies of the plan to the Washington state Congressional delegation. Regional officials, who resided in the Seattle area, were well aware that the Klondike had played an influential role in Seattle's history. The role was particularly evident in the early 1970s, as the city prepared its two-year "Klondike Festival" to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the gold rush. By June 1971, as noted above, NPS official Rod Pegues was tilting in favor of a Seattle unit, and by September, the NPS had gone on record in support of it. The following January, Mayor Uhlman became an enthusiastic supporter as well. [43]

Planners originally conceived that the Seattle unit would consist of the Pioneer Building, a turn-of-the-century, multi-story structure on the east side of Pioneer Square. In 1971, the Pioneer Building was in imminent threat of being razed, so the NPS proposed that the agency purchase and restore it. But during the summer of 1972, Mel Kaufman and Tim Morgan purchased a 50 percent share in the Pioneer Building, and with co-owner Jack Butnick announced restoration plans. [44] For the next two months, NPS planners continued to assume that they would purchase the building, then lease out those areas not needed by the agency. An NPS appraisal, however, revealed that an adaptive restoration of the Pioneer Building would cost $7.4 million. Such a cost was far more than Congress was ever likely to authorize for such a project. By April 1973, therefore, planners reluctantly decided to lease space within the building rather than purchase it. [45]

Eagle, Alaska, and other sites were briefly considered, but later rejected, as units of the proposed international park. Governor Egan first broached the idea of Eagle's inclusion in February 1971. (The Eagle Historic District, which included the non-native townsite and Fort Egbert, had been added to the National Register of Historic Places just one year earlier.) Seven months later, at the initial meeting of the Klondike Gold Rush International Advisory Committee (KGRIAC), members from the two countries agreed that "the Park concept should be confined to Seattle-Victoria (and/or Vancouver), Skagway/Dyea, Chilkoot-White Pass-Bennett, Whitehorse-Yukon Historic Waterway, [and] Dawson-Bonanza Creek-Eagle." [46] By February 1972, a briefing statement elaborated on the concept, noting that

The proposed park will have units in Seattle, Vancouver, Victoria, Skagway, and Dawson City. It may also include Eagle.... The development concept for Seattle, Victoria, and Vancouver consists of restoration of one or two buildings in each place for use as a visitor center and museum.

Soon afterwards, the NPS toyed with the idea of including both the Eagle historic district and Circle in the proposed park. But the Bureau of Land Management made a recreational withdrawal of the Eagle area in mid-1972, and the NPS, which was developing plans for a major park unit in the nearby Yukon-Charley Rivers area, did not protest the move. The NPS's draft master plan, issued in June 1972, contained no references to either the Eagle or Circle areas, nor did any other planning documents issued after that date. [47]

The International Advisory Committee

After the 1969 Labor Day hike, parks officials from both countries had made it clear that they wanted to coordinate their efforts over the long term. Ted Swem and Peter Bennett, meeting in Whitehorse on September 4, recommended that the two countries should

set up an International Advisory Committee for consultation in connection with the planning of the program, with representation from appropriate State, Provincial and Territorial Governments as well as the Federal Government Departments concerned, but with the development and operation of the program to be entirely in the hands of the respective National and Historic Park Services....

No such committee was mentioned at the time of the joint accord agreed upon by Hickel and Chrétien that December. Just a week afterwards, however, NPS personnel presented Hickel with the idea of a 13-member Klondike Gold Rush International Advisory Committee. On February 9, he passed that suggestion on to Chrétien, who was equally enthusiastic about it. [48]

The idea of an international committee to coordinate national park planning was not new. The Canada-United States Joint Committee on National Parks had first met in Ottawa in 1967. It had been established informally, by an exchange of letters between the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and the Secretary of the Interior, rather than through diplomatic channels. Since then, it had met annually; at Everglades National Park in 1968, and in Jasper National Park in 1969. [49]

Once the two agency heads had agreed to the committee's establishment, more than a year elapsed before official letters were exchanged and the necessary committee members could be appointed. [50] The first meeting took place in September 1971 in Whitehorse. The committee, as finally constituted, consisted of five Americans and eight Canadians. The U.S. members consisted of the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, the Director of the State Division of Lands, the Mayor of Skagway, and two outsiders; Canadian members included the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, the Deputy Provincial Secretary of British Columbia, the Executive Assistant to the Yukon Commissioner, the mayors of Whitehorse and Dawson City, and three outsiders.

The Klondike Gold Rush International Advisory Committee (KGRIAC) remained an active organization for most of the remainder of the decade. During that period they played a crucial coordinating function. The full committee met twice annually during 1972 and 1973; in addition, several subcommittees met in order to investigate specific problem areas. The full committee met once per year in 1974 through 1976. But the authorization of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, on the U.S. side of the border, removed much of the committee's reason to exist. It met just once more, in 1978, then faded away. [51]

Canadian Park Developments, 1971-1973

In 1970, as noted above, the National and Historic Parks Branch decided that a consulting company should be employed to formulate a provisional master plan study of the Chilkoot Trail. That consultant, Canadian Environmental Services, Ltd. of Vancouver, was selected in April 1971. CES quickly assembled a study team which included, in addition to its in-house staffers, three outside experts: author Pierre Berton, Jack Shadbolt, a well-known painter; and Abraham Rogatnick, a professor of architectural history. The CES team travelled to Skagway in August and, as noted above, hiked the Chilkoot in conjunction with NPS, state, territorial, and provincial officials. Working in conjunction with an international advisory team, the consultant issued a February 1972 report which proposed that the Chilkoot portion of the Klondike Gold Rush International Park include a hotel at Bennett, along with campsites and cooking shelters at Happy Camp, "Bridge Camp" (Deep Lake), Lindeman, and Bennett. It recommended that a spur road be constructed from the proposed Skagway-Carcross Road into Bennett, and that sites in the Gastown area of Vancouver and the Bastion Square area of Victoria be chosen similar to what the NPS was doing in Seattle's Pioneer Square. The National and Historic Parks Branch, upon receiving the report, noted that it "was not in full agreement with many of the statements and the way they are presented." In particular, the agency felt that "apart from emergency shelters we should not provide permanent type accommodation between Sheep Camp and Lindeman Lake." [52]

Meanwhile, planners had to contend with more immediate concerns. In January 1972, a National and Historic Parks Branch official, V. P. "Sandy" Rolfson, recommended the implementation of a protection and interpretation program on the Chilkoot. Such a program was needed to provide public safety and supervision, to catalogue and photograph artifacts, and to mark and maintain the trail. In order to develop the program, Rolfson urged the construction of a headquarters camp at Bennett and an overnight camp in the vicinity of Chilkoot Summit or Crater Lake. Three patrolmen would be needed to guarantee public safety, while additional personnel would be needed to catalog and store trailside artifacts. The Western Regional Director, Ron P. Malis, recognized that artifacts along the trail were quickly being lost and consented to the cataloguing proposal. [53]

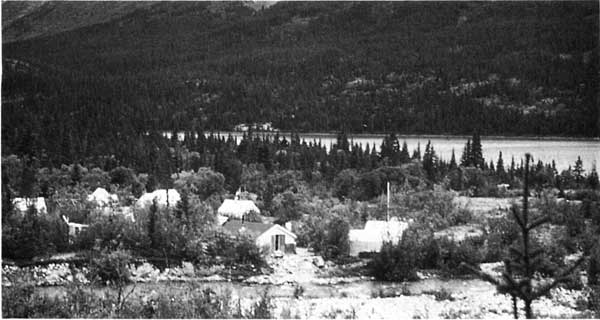

To carry out the cataloguing plan, a special summer employment program under the supervision of Bruce Harvey brought four students--Bill Massé, Ken Berube, Alex Hermann Kerr, and Andrew Holmes--out to the trail in July and August 1972. The four lived at Lindeman Lake in three 10' x 14' plywood-and-canvas tents which were constructed for their use by members of the nearby Corrections crew. The quartet took 240 photographs of artifacts and building remains, each keyed to catalogue cards and located on a topographic map. Upon the advice of a regional office curator, some of the most valuable artifacts were brought back to Whitehorse and placed in storage in the National and Historic Parks Branch warehouse. [54]

Central to the establishment of any park unit on the Canadian side was the transfer of potential park land from British Columbia to the Federal government. To effect that transfer, Peter Bennett of the National and Historic Parks Branch contacted L. J. Wallace, British Columbia's Deputy Provincial Secretary, in the spring of 1972. For the next several months, provincial officials weighed the value of the proposed park over possible resource utilization in the area. Finally, in mid-June 1973, Jean Chrétien, the Minster of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, reached an agreement in principle with Jack Radford, British Columbia's Minister of Recreation and Conservation. Part of that agreement provided for the eventual transfer of some 80 square miles from the province to the federal government and allowed the inclusion of that parcel in the Chilkoot Trail Unit of the so-called Klondike Goldrush International Historic Park. The parcel in question included the Chilkoot Trail corridor, along with the adjacent drainage to the west. [55] All signs seemed to point to the creation of a large historic park on the Canadian side of the Chilkoot Trail.

By the time Chrétien and Radford had signed their historic agreement, a second year of Chilkoot Trail field work had begun. Due to the efforts of Bruce Harvey, a second group of students continued the previous year's work. Alex Hermann Kerr, who had been part of the 1972 crew, returned to the trail; he was joined by Bruce Murphy, Collyne Bunn, and Patricia Smith. A corrections crew was also deployed that summer for trail maintenance purposes. [56]

The Yukon-Taiya Commission Concludes Its Work

As noted in Chapter 3, the Yukon-Taiya Commission had been established by the 1967 Alaska Legislature in order to provide a forum for the investigation into the area's hydroelectric resources. The commission, however, was not funded until 1968, and its first meeting was held that fall. Elmer Titus, from Ketchikan Public Utilities, was appointed as chairman. The remaining committee members included Glenn Waterman, an Anaconda Ltd. executive from Britannia Beach, B.C.; Don Mellish, the president of the First National Bank in Anchorage; Elton E. Engstrom, the Juneau-based state senator who had organized the effort to create the commission; and Malcolm Moe, the former mayor of Skagway.

Just a few days before the commission was to meet, the primary focus of their efforts became clear. In Ottawa, personnel from the U.S. Embassy met with officials from the Canadian Department of External Affairs (i.e., Canada's Department of State) and exchanged International Notes for a cooperative power market potential study. U.S. efforts would be organized by the Juneau-based Alaska Power Administration, part of the Interior Department, while Canadian efforts would be organized by the Department of Energy, Mines, and Resources. Together, the two agencies formed the ad hoc Canadian Upper Yukon River study group. [57]

The commission's first meeting took place in Juneau on December 20, 1968. Recognizing that project development would depend first and foremost on the development of new power sources, commission members asked several Federal agencies involved with mineral exploration to ascertain the area's mineral development potential. [58]

When the commissioners met again three months later, they obtained updated information on Alaska and Yukon minerals potential. They were informed, however, that there was little present demand for new power. One expert noted that in order to justify the 400,000 kilowatts which would be generated by such a project, 20 to 50 new mines--each within economic transmission distance of the project--would have to be developed. Even under an optimistic development scenario, such demand was not expected until 1985. The commission responded to the news by demanding an expedited minerals exploration program. [59]

The commission met in Anchorage in December 1969, and again in Juneau in April 1970. By this time, the U.S. and Canadian authorities had announced their intention to create a park which included the Chilkoot Trail. Commission members knew that such a park could ruin any hydroelectric development plans, so they passed a resolution which "strongly recommends that the power project be designated the prime use of the area and that the historical trail be developed in concert with this primary use." [60] Those concerns were relayed to state and federal authorities. As noted above, most Alaska officials agreed with the commission, while Federal officials (most notably Interior Secretary Hickel) felt that the two uses were not necessarily incompatible. Because of the state's concerns, both the master plan and proposed legislation contained a provision which insured that the park's establishment could in no way jeopardize future hydroelectric development in the Taiya Valley. [61]

At their April 1970 meeting, commission members received a progress report on the work of the Canadian Upper Yukon River study group. They recognized, however, that they could do little until the group had completed a preliminary draft of its power market potential study. [62] The report, scheduled to be completed by the end of 1970, had still not been completed by September 1971, so the commission which convened in Skagway that month visited the proposed development site and was updated on the study's progress, the park proposal, and other relevant matters. [63]

By October 1971, it had become apparent that little was to be done regarding the joint study in the foreseeable future. Data and preliminary views relating to power potential had been exchanged between the two countries. The data thus far gathered did not support further water development, and no further studies were planned. [64] Yukon Commissioner James Smith, perhaps reflecting the prevailing mood in Canada, was quoted as saying, "As far as the Taiya power project is concerned, it was just a glimmer in somebody's eye which could be written off and forgotten." [65]

By the following January, Alaskans had arrived at the same glum conclusion. Rush Hoag, an economic development consultant, published The Promise of Power, a Commission-sponsored study of southeastern Alaska's power potential. (Hoag had completed a similar study for the state Department of Economic Development three years earlier.) Hoag concluded that because power costs in Southeast were not significantly lower than those in major industrial centers, the development of large power sources would depend upon processing domestic raw materials rather than imports. The region did not have readily-accessible raw materials that demanded new power sources; there was little immediate need, therefore, for the Yukon-Taiya project. Hoag recommended that two other power projects be constructed in southeastern Alaska before serious consideration be given to Yukon-Taiya. [66]

The Fate of the Pullen Collection

As noted in Chapter 2, owner Mary Kopanski moved the Pullen Collection out of Skagway shortly after the Pullen House closed in 1959. The collection was stored in a new, fireproof building in Lynnwood, Washington (a suburb of Seattle) where it remained until shortly after the completion of the 1962 Seattle World's Fair. At that time, much of the collection was displayed in a building in Seattle Center (the site of the fair), where it remained for another ten years. Many hoped that the stay in Seattle would be only temporary and that the collection would soon return to Skagway. [67]

In 1972, however, a new crisis loomed. Seattle Center's management announced plans to remodel its facilities, and informed Mrs. Kopanski that the collection would need to be moved. Citing financial difficulties, she responded by declaring her intention to sell the collection. [68] She expressed the hope that the entire collection could be sold to a museum or other facility that would be able to properly curate and display her grandmother's memorabilia. Many Alaskans, particularly those who had seen the collection, were similarly hopeful that the collection could remain together, preferably in Alaska. They recognized that if no institutional purchaser could be found, the collection would have to be sold off piecemeal, something that was to be avoided if at all possible.

Speculation on potential purchasers of the collection centered on either the federal or state government. The NPS, which had shown an interest in the collection in the initial draft of the master plan, reiterated the need to preserve the collection. They could do nothing, however, until Congress authorized the establishment of the park--something that was not expected for several years.

Action then moved to the Alaska legislature. On January 24, 1973, the Alaska House and Senate introduced bills which would have authorized $200,000 to purchase the Pullen Collection and display it in the Alaska State Museum. [69] House Bill 125 was passed out of the State Affairs Committee on February 1 on a 2-1 vote; on February 27, it passed the House Finance Committee, 6-2. Three days later, it passed the House on a 31-9 vote. [70]

On March 6, the bill was sent on to the state senate, where it received a rocky reception. On April 3, HB 125 lost a Senate Finance Committee vote, 3 to 2. The two Democrats, one of whom was Bill Ray of Juneau, voted in favor of the bill. All three Republicans, however, voted against it, one of them noting that "We cannot afford this luxury." Despite the setback in the Finance Committee, the bill was forwarded to the full Senate for its consideration. On April 7, the last day before the Senate was to adjourn, the Senate voted 11 to 9 against returning the bill to the Finance Committee; shortly afterward, the Senate voted 12 to 8 in favor of HB 125. Because Governor William Egan, a Democrat, had announced his intention to sign the bill, its passage by the Senate appeared to be the last hurdle needed in order to preserve the collection and keep it intact. [71]

After the Senate completed its vote, however, Senator Clifford Groh (R-Anchorage), the Finance Committee chair, gave notice of reconsideration of his vote. A notice of reconsideration is a procedural motion that holds the bill over until the next legislative day. Groh, who had previously voted against HB 125 when it had been in the Finance Committee, effectively killed the bill for the 1973 legislative session by utilizing this parliamentary maneuver on the last day before adjournment. [72]

Faced with stonewalling by the state and federal governments, and with few other financial reserves, Kopanski decided to sell the collection on the auction block. From July 1 through July 5, 1973, James Greenfield of Seattle's Greenfield Gallery sold some 5,000 items, organized into 2,238 lots. Museum curators from six states along with scores of independent collectors attended the auction. The sale of the collection, held at Greenfield's auction house, brought Kopanski significantly more than the Alaska legislature was willing to offer. Sources variously estimate that she grossed anywhere from $269,000 to $350,000. [73]

The Skagway-Carcross Road

As noted in Chapter 2, Skagway citizens had been lobbying for a road across White Pass since the century's opening decade. The city council, the chamber of commerce, the media, and individual citizens had repeatedly taken the matter up with state, federal, and Canadian officials. Local residents, over the years, had often been given verbal support for their efforts, but during the Territorial period funding levels were never sufficient to provide more than token construction work.

Skagway residents, and economic development interests throughout Alaska, hoped that statehood would bring sufficient funding for a road to Carcross. Initial signs, in fact, were optimistic. In the fall of 1960, Alaska's Department of Public Works was allotted $1 million to extend the highway another mile toward White Pass, and in the summer of 1961 the road was extended from Black Lake to Porcupine Creek. [74] In the meantime, Alaskans regularly discussed the road, and similar topics, with their counterparts in British Columbia and the Yukon. [75] In March 1961, Alaskans were dismayed to hear that the huge Battelle Memorial Institute report on north-country transportation routes, Transport Requirements for the Growth of Northwest North America, did not recommend that the road be built. But they knew that the Alaska Marine Highway System would soon be operating and felt confident that pressure to construct a highway would follow soon afterwards. [76]

During the 1960s, as in previous decades, local residents used every opportunity at their disposal to push for a road. [77] Area leaders were sensitive to those concerns, and in September 1964 the Premier of British Columbia, the Yukon Commissioner, and the Governor of Alaska jointly supported the idea of a Skagway-Carcross road. [78] No action followed their resolution, however. The following year, the need to re-energize the effort induced volunteer parties at both ends of the highway to extend the road, if only to a symbolic degree.

In the federal election of 1965, Canada's Progressive Conservative party announced that they would build their share of the road immediately if successful at the polls. The Liberals, however, were successful. Despite that setback, the Canadians made a preliminary survey of the road the following year. That fall, the Alaska Highway Department upgraded the 2-1/2 miles of existing roadway. [79]

The NPS also became interested at this time. Roger Allin, a Washington-based planner who had extensive experience in Alaska, wrote a document which called for the designation of five scenic roads in Alaska, the road between Skagway and Carcross being one. Allin, who was convinced that the highway would be built in the "early future," noted that "Scenic road concepts and standards to guarantee the appropriate development of this beautiful and historic valley should be important elements in such construction." [80]

In 1967, a series of events rekindled local interest in the road. In March, the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development asked Travacon, a Calgary consulting firm, to study the Yukon transportation system. As part of that study, the consultants spoke about the Skagway-Carcross road to various Alaska commissioners; in addition, Canadian officials visited the proposed right-of-way that spring and did some preliminary survey work. Then, in September, Senator Ernest Gruening visited Skagway. Gruening knew that Congress was set to give Alaska a substantial payment for highway improvement, so he suggested that a petition be gathered to show local support. Skagway resident Ed Feight obliged him, and before long a 300-signature petition had been sent to Governor Hickel. During his visit, Gruening received the White Pass company's approval for the proposed road. (Many local residents had worried that the railroad would fight against the proposed highway.) State legislators did what they could to push the road as well. On February 23, 1968, senators Elton Engstrom and John Butrovich introduced a resolution (SJR 44) which advocated the highway's construction, both on the U.S. and Canadian side of the border. The resolution, however, did not get beyond the committee stage. [81]

The Canadian study, which was completed in 1968, concluded that a Skagway-Carcross road "would offer some advantages, but these would not be sufficient to offset its high costs." Although they were tepid to the idea of a road to Skagway, officials from the Canadian Department of Public Works agreed to meet on the matter with their counterparts in the Alaska State Highway Department. The meeting took place in Skagway in the summer of 1969. At that meeting, officials agreed to again study the feasibility of the proposed road. That survey was completed in June 1970. [82]

Meanwhile, both the Americans and the Canadians were gradually improving their roadway. In 1969 state maintenance crews upgraded the five existing miles of roadway near Skagway; in 1970, a new bridge was constructed at Carcross; and in 1971, in conjunction with activity at the Venus Mine, construction crews extended the Klondike Highway 2.5 miles to the Yukon-British Columbia border. [83] The summer of 1971 also witnessed the continuation of aerial surveys over the proposed right-of-way. The British Columbia government, however, refused to support the road because they saw no benefit in it for themselves. [84]

Planning finally turned into decision making in 1972. In February, Commissioner James Smith of the Yukon announced that the federal government had agreed to build and maintain the 33.6 miles of road needed to cross British Columbia. That same month, Alaskan officials also agreed to construct the 9.4 miles of road that would be needed to complete the highway, and proceeded to prepare a draft environmental impact statement for the project. (The DEIS was completed later that year.) The only remaining hurdle to progress was British Columbia's grant of a right-of-way to the federal government. [85] In the fall of 1972, B.C. Premier David Barrett met with Governor Egan and assured him that provincial officials "would do their share and would proceed to work out details with Ottawa." By December, the B.C. government finally agreed to grant the road right-of-way; Canadian federal officials, as a result, got ready to make firm commitments for funding their portion of the highway. [86]

In March 1973, in anticipation that road construction was in the offing, state highway officials held a hearing in Skagway on the proposed right-of-way; as part of that hearing, they described why the so-called West White Pass route was favored over routes which crossed Chilkoot Pass or Warm Pass. Soon afterwards, city, state, and federal officials met in Skagway to ensure that the proposed construction would minimally impact the Skagway and White Pass Historic District. [87] The road enjoyed broad support. The only dissent came from conservationists, who worried that the construction of a road would jeopardize the historical values found along the White Pass Trail corridor. [88]

Finally, on June 13, 1973, road construction was assured when Northern Affairs Minister Jean Chrétien met with Jack Radford, British Columbia's Minister of Recreation and Conservation. In the same agreement which expressed the province's willingness to transfer its lands for park purposes to the federal government, Canada announced its intention to cooperate with the United States in the construction of the Skagway-Carcross road. Soon afterwards, Governor Egan praised the Canadian officials' pact and detailed the state's plans regarding the road. Recognizing the need to plan for a historical park in the Skagway business district, officials from the city, state, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation met in Skagway and agreed to reroute the state highway from Second Avenue to First Avenue, to replace the existing bridge across the Skagway River, and to construct 9.4 miles of new road to the Canadian border. Leaders from both countries hoped that initial construction would take place later that summer and that the road would be completed by 1976. [89]

The announcement of the highway's construction gave Skagway residents the outlet to Canada that they had been anticipating for over 60 years. The selection of the West White Pass route, moreover, reduced the pressures which had intermittently arisen over the years for construction of alternate routes. Interest in a highway over Chilkoot Pass, for example, had first surfaced in 1950, shortly after the road to Dyea was completed, and in 1961 a state official noted that a proposed route for the Skagway-Carcross road ascended the Taiya River valley. [90] The idea re-emerged in 1971, when an assistant to Governor Egan openly worried that the NPS would prevent the construction of a Chilkoot Pass highway. The following year, the Alaska Highways Commission recommended such a highway to Senator Ted Stevens (R-AK), but by the fall of 1972, NPS planners had been assured that the state had no plans to build a road over Chilkoot Pass. [91] Another road that was proposed during the early 1970s would have gone from the Log Cabin area to Bennett. The province of British Columbia, which hoped to develop the area, was behind the idea. The Klondike Gold Rush International Advisory Committee, however, was firmly against a road to Bennett; perhaps for that reason, plans for its construction were shelved. [92]

The NPS had no qualms with the construction of the Skagway-Carcross highway. At no point did the agency oppose it. It recognized that the road would not only stimulate tourism to the Skagway historical district, but it would also provide an access point to the park's White Pass unit. The Park Service even offered the state the services of a landscape architect in order to minimize the adverse impacts of construction. [93] The state, however, had difficulty accepting the NPS boundaries proposed in the June 1972 revised draft master plan, because it showed the proposed highway passing through the White Pass Unit. Instead, it argued that the NPS recognize the existence of a designated highway corridor. [94] The NPS, responding in the master plan, reiterated its support for the road but did not provide for a designated corridor. The agency specifically intended that the road would become an access road to the proposed park; in fact, the boundaries of the White Pass Unit were configured to give the NPS full management control over a trail which would connect the road to the White Pass City area, the Brackett Wagon Road, and the White Pass Trail. [95] For awhile in early 1973, the conflict between the state and the NPS resulted in a proposed park boundary that parallelled the road's right-of-way. Later, however, the boundary was extended west to the next section line, where it remains today. [96]

Although some authorities were confident that the road could be constructed in two or three years, more than five years would elapse before the project was completed. On the Alaska side, the surveyors finished their work in 1973 and bids opened for road construction in July 1974. [97] By October, Central Construction Company of Seattle was awarded a $10.9 million contract. [98] Work began immediately. By the end of 1975, a pioneer road had been roughed out as far as Captain William Moore Creek, and by August 1976 the bridge across the creek had been completed. [99] By year's end the road had been pushed a mile beyond the bridge, and by September 1977 workers were able to report that the completed highway was "within sight of the border." By season's end, the highway had been blasted as far as the summit. [100]

Canadian crews had to construct far more roadway than the Americans, so two different construction contracts were let. By October 1973 the first contract had been let to Ben Ginter Construction, Ltd. of Prince George, B.C., for 16 miles of roadway between the Yukon-B.C. border and the south end of Tutshi Lake. That contract should have been finished by the end of the 1974 season, but project work was delayed for a full year. Construction work was stalled for so long that the Alaska legislature passed a resolution calling for a "timely completion" of the highway; a more strongly-worded resolution, calling for the two countries to complete the road at the same time, died in a House committee. [101] The second contract, for the remaining 20 miles of the highway, was let in the spring of 1976 to General Enterprises, Ltd. of Whitehorse. [102] By September 1977, General had completed a tote road to within seven miles of the border. They finally reached the border on July 28, 1978, and by September 1, construction workers were able to drive over White Pass summit. [103] A few hardy Skagway residents were able to drive to Whitehorse that year. Most, however, waited until 1979 to use the new road. [104] The highway was dedicated on May 23, 1981 at the Liarsville campground, near Skagway. [105]

During the early stages of the road planning effort, the NPS demanded that a turnout--intended as a viewing area and trail head--be placed within the mile-long stretch of road included within the proposed park boundaries. [106] During the summer of 1975, the NPS was called on to select a specific location for the turnout. A location was suggested which would provide a view of White Pass City; a proposed signpost would describe the history of the White Pass area. [107] The NPS intended, at this time, to have only one interpretive location along the Skagway-Carcross road. By the time construction took place, however, authorities decided that a second pull-out (located between Black Lake and the Porcupine Creek crossing) was necessary as well.

Congress Introduces a Park Bill

Alaska's Congressional delegation introduced the first bills to establish Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in April 1973. By that time, the NPS had been working for more than two years on the language to be contained in such a bill. Work had begun in January 1971 when the Western Service Center had completed the preliminary master plan. The preparation of a planning directive and legislative support data allowed officials to begin compiling a draft legislative bill in April 1971. Senator Stevens and NPS officials cooperated in preparing the text for the bill, and in January 1972, a preliminary draft for a 22,000-acre park was shown to Governor Egan. [108] By March, the agency had shown a new draft of the bill (revised because of state objections) to the remainder of the Alaska Congressional delegation, and Stevens informed the agency that he planned to introduce a park bill that summer. [109] In August, however, Stevens notified regional officials that "it would probably be too late to hold hearings on it this Congress," and action was delayed until 1973. [110] For the next nine months, the language of the proposed bill changed several times in order to conform with ongoing changes in the park's master plan.

By April 2, 1973, the draft bills were ready to be submitted. Stevens planned to introduce a bill on April 17, and fellow senator Henry Jackson (D-WA) had already agreed to co-sponsor it. [111] On the 17th, Stevens introduced S. 1622; it was co-sponsored by senators Jackson, Mike Gravel (D-AK), and Warren Magnuson (D-WA) The same day, Representative Don Young (R-AK) introduced an identical bill (H.R. 7121) in the House of Representatives; it was co-sponsored by Brock Adams (D-WA) and Joel Pritchard (R-WA). Adams and Pritchard had special reasons for joining as early co-sponsors; Adams's district covered part of the Pioneer Square historical district, including the Pioneer Building, while Pritchard's district covered the remainder of the Pioneer Square area. [112]

Once the bills were submitted, they were filed in the Senate and House Interior and Insular Affairs committees. There they waited for committee action. Meanwhile, the regional office prepared legislative support data packages for the proposed park. [113]

The National Park Service, which had worked with Congress in the preparation of the two bills, agreed with most of the language contained within them. On December 16, 1973, however, it recommended four amendments to S. 1622, and a month later, it recommended two more. Of the six, only two were substantive. First, the NPS urged that the park's maximum size be increased from 12,000 acres to 13,300 acres, in order to coincide with the areas the NPS had identified as being required for the park. The second amendment dealt with the Yukon-Taiya project. The original bill, as crafted by Congress, contained a subsection which specifically authorized the construction of the Yukon-Taiya power project and the use of lands and waters within the park for the project. The NPS, in response to that subsection, had no quarrel with the intent of that language. But an Interior Department lawyer recommended that reference to the project be deleted, since Congress--regardless of the bill's contents--was capable of authorizing the project should it wish to do so. [114]

In February 1974, the park master plan was released. That same month several Alaska House members, including local representatives Mike Miller and Mildred Banfield, introduced House Joint Resolution 74, which advocated the passage of a Klondike park bill. Within a month the resolution had passed both chambers with unanimous votes, and on March 11 Governor Egan signed the measure. In mid-May, the Juneau Chamber of Commerce approved a similar resolution, and on June 17, the Seattle City Council did the same. [115]

Although the bills to authorize the park, by this time, enjoyed broad support, they did not receive Interior Department approval until May. They were then sent to the Office of Management and Budget where they were held up for several months. When the bills emerged from OMB, Ted Stevens asked Alan Bible, the chairman of the Senate Parks and Recreation Subcommittee (part of the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee), to schedule hearings on S. 1622. By that time, however, the session was winding down. As a result, neither S. 1622 nor H.R. 7121 were acted upon by their respective committees during the 93rd Congress. Signs were good, however, for action in the next Congress. A logjam of other park legislation was being cleared away, and the Interior Department had recommended that the Klondike park proposal be included in President Ford's legislative program. [116]

During this period, the Canadians also hoped to make progress on the establishment of a park in the area surrounding the Chilkoot Trail corridor. The Chrétien-Radford announcement of June 13, 1973 portended continued momentum toward a new park. After that announcement, however, the park proposal got bogged down in British Columbia's bureaucracy. Jack Radford, the Minister of Recreation and Conservation, hoped to proceed with park plans, but the Provincial Water Resources Chief Engineer was less than enthusiastic about the idea. The engineer objected to the 80-square-mile land transfer because the Chilkoot Trail corridor was still covered by a power withdrawal, made in February 1949, that had been related to the proposed Yukon-Taiya Project. (See Chapter 2.) To the engineer, the ability to develop that power had to be preserved. Another roadblock that arose during this period was one of aboriginal land rights; the B.C. government did not recognize these rights, and the province feared that a land transfer with the Federal government (which acknowledged Native land rights) might imply that the provincial government similarly recognized them. The Provincial Environment and Land Use Committee was given the task of resolving these conflicts. In the meantime, no action took place on the land transfer. [117]

Skagway Preservation Efforts

The National Park Service had decided, almost from the beginning of its involvement, that preservation controls would have to be enacted if a park unit in Skagway was to have any real chance of success. Thanks to the Alaska State Housing Authority, the city's first zoning map had been created in 1964 as part of a comprehensive plan. Included in that map was a Skagway Historical Zone. But Skagway had neither a historic ordinance nor any other kind of zoning ordinance.

In March 1969, NPS planner Bailey O. Breedlove consulted officials from the Alaska State Housing Authority, the Anchorage Area Borough, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Soon after, he began to fashion a model Historical Preservation Zoning Ordinance. As noted in Chapter 3, the Skagway Alternatives Study of March 1969 suggested that the city, as a prerequisite to NPS involvement, would be required to adopt 1) a zoning ordinance with a strict definition of "the historic district," and 2) a Historic Advisory Board to advise the Mayor and City Council on matters of historic preservation. [118] The agency approved the implementation of the alternative which included these provisions. Two years later, the park's preliminary master plan noted that the city would need to 1) "establish by ordinance the historic district..." and 2) "adopt local zoning laws which would help to preserve the historic integrity of the privately owned remaining historic buildings within the historic district...". [119]

NPS planners--chiefly Rod Pegues, assisted by Laurin Huffman--then worked with the city in order to establish an appropriate historic district zoning ordinance. At first, agency officials were unsure whether it was legal for the city to enact such an ordinance. (No other city in Alaska had a specially-zoned historic district.) Both the Interior Department Solicitor and the state Attorney General, however, issued opinions stating that the city could legally do so. [120] Over the next few months, Pegues worked with the Skagway City Council and the city attorney to craft a citywide zoning ordinance which provided for a historic district. That ordinance was finally presented to the City Council in the summer of 1972. It was given its third reading and was passed at the October 3 council meeting. The new ordinance called for the creation of the Skagway Historic District (or zone) with boundaries identical to those called for in the second draft of the master plan. The new ordinance, which became effective in November, was administered by the city's planning commission. There was no attempt at this time to establish a commission specifically for historic district affairs. [121]

During this period, several owners of Skagway's business properties contacted the NPS seeking architectural advice. The old Idaho Saloon, at the northwest corner of Third Avenue and Broadway, had suffered a fire in early 1972. Repairs were needed. [122] The Principal Barber shop changed hands, and the new owner hoped to restore it. Verbauwhede's Confectionery suffered a fire in the fall of 1973, and restoration of the Nettles hardware store was proposed. [123] The owners of these and other local historical properties were aware that their investments were becoming increasingly valuable, and all were eager to obtain the services of a historical architect if one were available. The NPS had an architect in its Seattle office, and promised his services to local residents. The architect, however, was constrained by his position; he could give general advice, for instance, but as a public sector employee he could not draw detailed plans and specifications. Besides, he was often too busy with other duties to provide much direct assistance. [124]

By the fall of 1973, the Skagway city council had finally moved to implement the provisions of the historic district zoning ordinance which had been created the previous October. John McDermott, owner of a business located in a Broadway historical building, was asked to head the Skagway Historical Commission. Other members included Jim Hamilton, Jean Richter, Jack Brown, Jewell Knapp, and Rex Hermens. As McDermott understood it, the commission's primary duty was to review and approve building plans for new construction or remodelling in the historic district. He and the other members, however, knew little about architectural detail. They prevailed on the NPS, therefore, for drawings, photographs, and other backup materials. [125]

In addition, John Rutter was able to relay their concerns to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The Trust responded by sending staff members John Frisbee, Robertson Collins, and Carol Galbreath to Skagway for two technical workshops which were held in mid-March 1974. NPS and State officials also attended. One workshop was held for the city manager, the Skagway Historical Commission, and the Skagway Planning Commission; another was presented at the high school for the community at large. The National Trust came away from their visit with a number of suggestions for improving the historical commission's function; many of those were packaged into an ordinance which passed the City Council later that year. [126]

By June 1974, it was evident that the historical commission was still having trouble getting started. In addition, local citizens became alarmed when cedar shingles began to be applied to the Nome Saloon, at the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Broadway. In response to those problems, and to a spate of new renovation activities, the commission invited NPS planner Don Campbell to Skagway. [127] The NPS recognized that many local architectural problems could be solved only with professional expertise. Therefore, it entered into a cooperative agreement with the city that July which called for an architect to provide regular consultation to the historical commission. [128] The man chosen to fulfill that role was Laurin Huffman, the Historical Architect in the Pacific Northwest Regional Office, who had been visiting Skagway since 1972. [129]

The Historic District Commission, which McDermott had organized in the fall of 1973, had its first regular meeting on October 24, 1974. NPS planner Don Campbell was in attendance. Two months later, the commission more than doubled in size, to 13 members. [130] Laurin Huffman, the NPS advisor, continued to consult with the commission on an intermittent basis. Interest in the commission, however, soon declined. It met only once in 1975, in May; meetings scheduled during other months were postponed for lack of a quorum. [131] The commission's inactivity resulted in the disestablishment of the historic commission within months of the park's authorization. The city planning commission assumed its functions and became the Planning, Zoning, and Historic Commission. [132]

The Role of the National Park Foundation

The National Park Foundation, which had become the owner of the former White Pass and Yukon Route depot in May 1971, became increasingly involved in the preservation of Skagway's buildings during the mid-1970s. The 1973 master plan, it may be remembered, proposed that the NPS purchase nine Skagway buildings, restore them, and retain them for interpretive purposes. Except for the two-building White Pass depot complex, the other seven buildings were privately owned. These included the three-building Mascot Complex, Boss Bakery, Boas Tailor and Furrier, the Tanner Building, and the Moore Cabin. The master plan also identified seven buildings which it hoped to purchase and restore, then lease back to private parties; these buildings included the Verbauwhede's Confectionery complex, the four-building Pack Train complex, the Principal Barber shop, and the Idaho Saloon. National Park Service officials were worried that many of these buildings would lose their historical importance if they were not immediately purchased. The NPS, however, could not purchase any buildings until the park had been authorized. The agency, therefore, enlisted the National Park Foundation to serve as a holding agency.