MENU

![]() Rocky Mountain

Rocky Mountain

|

Glimpses of Our National Parks |

XII

XII

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK

COLORADO

Special Characteristics: Continental Divide; Peaks 11,000 to 14,255 feet Altitude; Heart of the Rockies; Interesting Records of Glacial Period

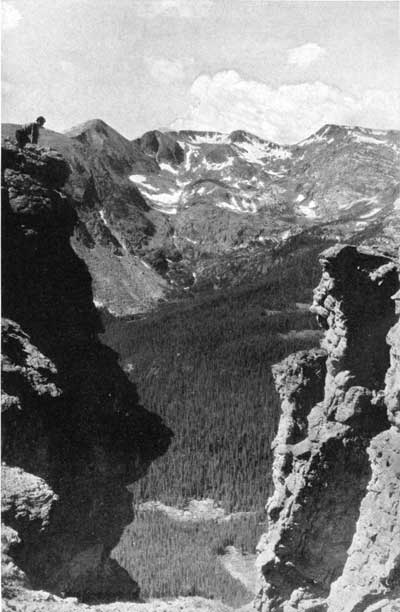

Continental Divide across Forest Canyon from Big Cut on Trail Ridge Road—Rocky Mountain National Park |

THE Rocky Mountain National Park is in Colorado, about 70 miles by road northwest of Denver. Find Longs Peak on a good map and there is the center of the snow-topped mountains which constitute this high-in-the-air park.

These mountains are part of the Continental Divide, which is the name given to the irregular line of high land running north and south through North America that divides the waters flowing eastward into the Atlantic Ocean from those flowing westward into the Pacific. For this reason the people of Colorado call their mountains the crest of the continent.

This national park is certainly very high up in the air. The summer visitors who live at the base of the great mountains principally at the beautiful eastern gateway, a little valley town of many hotels, which is called Estes Park, are 7,600 feet, or a mile and a half above the level of the sea; while the mountains rise precipitously nearly a mile, and sometimes more than a mile, higher still. Longs Peak, the giant of them all, rises 14,255 feet above sea level, and most of the other mountains in the Snowy Range, as it is some times called, are more than 12,000 feet high; several are nearly as high as Longs Peak.

AT TIMBER LINE

The valleys on both sides of this range and those which penetrate into its recesses are dotted with lovely parklike glades clothed in a profusion of glowing wild flowers and watered with cold streams from the mountain snows and glaciers. Forests of pine and silver-stemmed aspen separate them. Timber line is more than 11,000 feet above sea level, and up to that point the slopes have a thick and close covering of spruce and fir, growing very straight and very tall.

Just at timber line, where the winter temperature and the fierce icy winds make it impossible for trees to grow tall, the spruces lie flat on the ground like vines, and presently give place to low birches which in their turn give place to small piney growths and finally to tough straggling grass, hardy mosses, and carpets of alpine flowers. Grass grows in sheltered spots even on the highest peaks and furnishes forage for the picturesque Rocky Mountain Bighorn that dwell far up in these high open places, and may sometimes be glimpsed on exposed ridges.

Even at the highest altitude gorgeously colored wild flowers grow in glory and profusion in sheltered gorges. As late as September large and beautiful columbines are found in the lee of protecting masses of snow banks and glaciers.

Above timber line the bare mountain masses rise from 1,000 to 3,000 feet, often in sheer precipices. Covered with snow in fall, winter, and spring, and plentifully spattered with snow all summer long, the vast, bare granite masses, from which, in fact, the Rocky Mountains got their name, are beautiful beyond description. They are rosy at sunrise and sunset. During fair and sunny days they show all shades of translucent grays and mauves and blues. In some lights they are almost fairylike in their exquisite delicacy. But on stormy days they are cold and dark and forbidding, burying their heads in gloomy clouds, from which sometimes they emerge covered with snow.

Often one can see a thunderstorm born on the square granite head of Longs Peak. First, out of the blue sky a slight mist seems to gather. In a few moments it becomes a tiny cloud. This grows with great rapidity. In 5 minutes, perhaps, the mountaintop is hidden. Then, out of nothing, apparently, the cloud swells and sweeps over the sky. Sometimes in 15 minutes after the first tiny fleck of mist appears it is raining in the valley and possibly snowing on the mountain. In half an hour more it has cleared.

Standing on the summits of these mountains the climber is often enveloped in these brief-lived clouds. It is an impressive experience to look down upon the top of an ocean of cloud from which the greater peaks emerge at intervals. Sometimes the sun is shining on the observer upon the heights while it is raining in the valleys below. It is startling to look down on the lightning.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIGHORN

This range was once a famous hunting ground for large game. Lord Dunraven, the English sportsman, visited it yearly to shoot deer, bear, and Bighorn, and acquired large holdings by purchase of homesteading and squatters' claims, much of which was reduced in the contests that followed. Now that the Government has made it a national park, the protection offered its wild animals is making it a successful wild-animal refuge.

These lofty rocks are the natural home of the celebrated Rocky Mountain Bighorn, which is much larger than any domestic sheep. These Rocky Mountain sheep, even the lambs, make descents down seemingly impossible slopes. They do not land on their curved horns, as many persons declare, but upon their four feet held close together. Landing on some nearby ledge which breaks their fall they immediately plunge again downward to another ledge, and so on till they reach good footing in the valley below. They ascend slopes surprisingly steep. They are more agile even than the celebrated chamois of the Swiss Alps, and are larger, more powerful, and much handsomer. To watch a dozen or more Bighorn making their way along the volcanic flow which constitutes Specimen Mountain in the Rocky Mountain National Park is a sight not easily forgotten.

LONGS PEAK AND THE GLACIER RECORDS

The prominent central feature of the Rocky Mountain National Park is Longs Peak. It rears a square-cornered, boxlike head well above the tumbled sea of surrounding mountain tops. It has, unlike most great mountains, a distinct architectural form, Standing well to the east of the range at about its center, it suggests the captain of a white-helmeted company; the giant leader of a giant band. It is supported on four sides by flanking ridges, suggesting the stone buttresses of a central cathedral spire. From every side it looks the same, yet remarkably different. One does not know Longs Peak until he has seen it from every side, and then it becomes to him not a mountain mass but an architectural creation.

Until 1868, when the first successful ascent was made by Maj. J. W. Powell of Grand Canyon fame, Longs Peak was considered unscalable. The most popular route to the summit today is through an opening in perpendicular rocks called, from its shape, the Keyhole, out upon a steep slope leading from near its summit far down to a precipice upon its west side. The east side of Longs Peak is a nearly sheer precipice almost 2,000 feet from the extreme top down to Chasm Lake, which was the starting point of a gigantic glacier in times long before man. Chasm Lake, which is reached by trail from the valley, is one of the wildest lakes in nature. It is frozen 11 months of the year.

There is no region in America where glacial records of such prominence are more numerous and more easily reached and studied than in Rocky Mountain National Park. The whole country has been fantastically cut and carved by gigantic glaciers of the prehistoric past. Their ancient beds, now grown with forests, their huge moraines, their cirques, or starting places, are, next to the vast mountains themselves, the most prominent features of the region. Fine small glaciers, remnants of former mighty sheets of ice, lie in sheltered gorges above the 12,000-foot level.

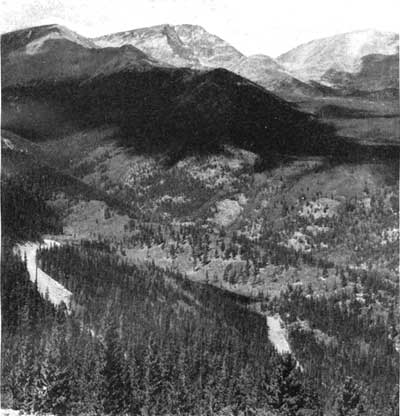

The Mummy Range and Mount Ypsilon from the Trail Ridge Road |

The Trail Ridge Road is one of the highest and most spectacular automobile roads in America. Its four-mile section over 12,000 feet in altitude is probably the longest stretch of road ever built at such a height. A trip across the park on this mountain highway is a never-to-be-forgotten experience. The road climbs to the very crest of the range and then follows the ridge. Valleys and parks lie thousands of feet below; rivers look like tiny silver threads and automobiles on the highways on the floors of the valleys seem to be only minute moving dots.

To the south an unexcelled view of the most rugged portion of the Front Range spreads out, while to the north, across Fall River Valley, the view is dominated by the majestic Mummy Range. Far to the west is the Never Summer Range. The mountain setting is superb.

ACCESSIBILITY

One of the striking features of the Rocky Mountain National Park is the easy accessibility of its peaks. One may mount a horse after early breakfast in the valley, ride up Flattop to enjoy one of the great views of the world, and be back for late luncheon. The hardy foot traveler may make even better time on these mountain trails, hiking across the Continental Divide from the hotels of one side to those of the other between breakfast and late dinner. Or one may motor via the Trail Ridge Road in a few hours.

Top

Top

Last Modified: Fri, Sep 1 2000 07:08:48 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/glimpses1/glimpses12.htm

![]()