MENU

![]() National Park System

National Park System

|

Glimpses of Our National Parks

THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM—HISTORY, ADMINISTRATION, AND USE |

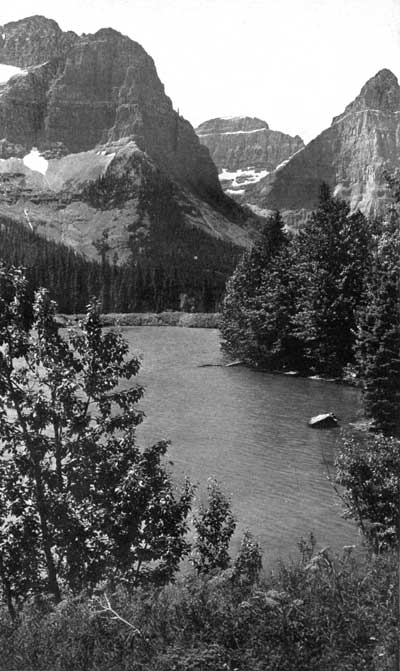

Upper End of Lake Janet, Glacier National Park |

THE United States has a system of national parks and allied areas—national monuments, national historical parks, national military parks and others—that is unparalleled in the annals of civilization.

That system came into existence nearly 70 years ago, when a group of average Americans voluntarily relinquished their legal and moral rights to profit through private ownership of the area now included in Yellowstone National Park.

They had been making a month's investigation of the Yellowstone region, a land of mystery visited only occasionally during the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century by Indians and by a few white trappers and hunters. Rumors of the geysers and hot springs filtered to the outside world.

As the exploration came to a close, the members of the party sat around a campfire one night discussing the marvels of nature viewed during the month just ending. They talked of filing claims on the land, then unappropriated public domain, one taking the geyser area, another the superb canyon of the Yellowstone River, and so on.

Then came the momentous suggestion that resulted in the creation of the first national park in this country or abroad. Cornelius Hedges, a lawyer of Montana, advanced the startling suggestion that the individuals of the party forego any ideas of personal gain and work for the reservation of the area as a national park for the perpetual use of the American people. The unique idea caught the imagination of the others in the party; they returned home, put their energies behind the project, and in 1872 were rewarded by the action of Congress in establishing the Yellowstone National Park "as a pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

Thus was born a new conception of land use. In 1872 the national park idea was little more than an ideal; a response to a vague urge that incomparable scenery be preserved for esthetic reasons, beyond the reach of utilitarian development.

Today national-park establishment and development are recognized as a major land use, vital to the well-being of the people of the Nation and to the preservation of our biologic resources. The National Park Service, a bureau of the U. S. Department of the Interior, was created by Congress in 1916 to manage the Federal park areas.

The entire world has followed the example of the United States, and today national parks or similar reservations exist on every continent, and in almost every country of any size.

NATIONAL PARK IDEALS AND STANDARDS

National parks in the United States, created by act of Congress, are areas of national significance distinguished by superlative natural scenery, set aside for preservation as nearly as possible in unimpaired condition and dedicated to the use and inspiration of the people. In establishing the Yellowstone, first national park, Congress quaintly designated it "a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people," and provided against "injury or spoliation of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural condition."

In establishing national parks no thought is given to geographic location. The area proposed for national park use is considered primarily from the standpoint of whether or not its principal features are of broad, national interest.

No consideration of commercialism enters into park creation. The major function is the promotion of the well-being of Americans, through the health-giving qualities of inspiration, relaxation, and recreation in pure, unpolluted air, in natural surroundings of inspiring grandeur.

Many of the parks contain noble forests, but the trees are preserved for their beauty and never considered as lumber. It is a strange fact, but often the trees that add most to the beauty of the landscape in reality have no commercial value.

There are many wild animals, but they never are considered from the standpoint of food supply. All hunting is forbidden except that called in park parlance "hunting with the camera." Many an erstwhile hunter, having laid down his gun for a camera while in a park, never cares to shoulder a gun again. The gentle-eyed deer becomes a friend, not an intended victim. The lesson of the national parks is that wild animals greatly fear man only when man is cruel and murderous. Another lesson from national parks' experience is that practically no wild animal will injure human beings except in self-defense. The monster cat of our rock fastnesses—the mountain lion—big enough and powerful enough to drag down a full-grown deer, is one of the most timid of all the beasts in the national parks, fleeing at great speed at the first sight or scent of man.

There are great waterfalls, but they are not harnessed. Outside the parks are more than enough falls to supply the power needs of the Nation. Those in the parks feed man's hunger for beauty—a demand that, long denied, seems stifled; but that given a chance in the unmarred outdoors thrives and increases and gives a broader outlook on life.

OTHER RESERVATIONS UNDER SUPERVISION OF NATIONAL

PARK SERVICE

In addition to the national parks there are several other classes of reservations in the national-park and monument system administered by the National Park Service. Previous to August 10, 1933, there were 22 national parks, 1 national historical park, and 40 national monuments under its jurisdiction. On August 10, under President Roosevelt's Executive order of June 10, 1933, the various park areas under the control of the Federal Government were consolidated in one unified system. At that time the name of the Service was changed to Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations. Five months later the original name of National Park Service was restored by congressional action.

In consolidating the various areas similar in concept and administration, 2 national parks, 11 national military parks, 10 national monuments, 10 battlefield sites, 4 miscellaneous memorials, and 11 national cemeteries were transferred from the jurisdiction of the War Department. Sixteen other national monuments, previously administered by the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture, were transferred to the enlarged system.

Jurisdiction over the park system of Washington, the Federal city, was also transferred to the National Park Service at that time.

Since the 1933 consolidation, normal growth has increased the Federal park system to 162 areas—26 national parks, 4 national historical parks, 82 national monuments, 11 national military parks, 8 national battlefield sites, 6 national historic sites, 1 national recreational area, 9 miscellaneous national memorials, 12 national cemeteries, 3 national parkways, and the National Capital Parks system. [1]

Although the national monuments constitute the largest numerically and most widely scattered group of the system, their precise meaning and purpose are not always understood. In order to insure the protection of places of national interest from a scientific, historic, or archeologic standpoint, Congress in 1906 passed a law known as the "Antiquities Act," which gave to the President of the United States authority "to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments." The exhibits in the existing national monuments run the gamut from the ruined dwellings of Indians who lived a thousand or more years ago to historic areas of the middle century; from trees and plants fossilized millions of years ago to magnificent groves of living trees.

Because of its limited size, this booklet describes only the national parks. Descriptions of these areas, arranged chronologically, begin on page 14.

PROPOSED INCREASES IN THE PARK AND MONUMENT

SYSTEM

The national park system is not yet complete. Nevertheless, only areas which meet the standards set up by the existing major parks are considered for inclusion in the system.

It is hoped eventually to make complete this national gallery of scenic, historic, and scientific displays. In the field of parks, for instance, Congress already has given authority for the addition of 2 important areas to the system. These are the Everglades in Florida, including tropical scenery and a rare tropical bird life, and the Big Bend area of Texas, with its steep-walled canyons, virgin forests, and abundant wildlife—the last wilderness area left in the Lone Star State.

These parks cannot be established until the lands within the approved boundaries have been acquired and donated to the United States. In connection with the Big Bend project, the Mexican Government has shown an interest in establishing a national park on its side of the international boundary, adjoining the proposed Big Bend Park, the two to form a great international peace park. This would be similar to the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, including Canada's Waterton Lakes Park and our own Glacier National Park now an established fact on our northern boundary.

Congress also has approved the Saratoga National Historical Park project, New York, and has expressed definite interest in the establishment of several national monuments in different parts of the country by authorizing their creation under terms similar to those affecting the national park projects. Saratoga National Historical Park project is now being developed with CCC funds and the area will be established as soon as title to lands is vested in the United States.

On August 22, 1935, the President approved the Historic American Sites Act, which gives the Secretary of the Interior, through the National Park Service, greatly broadened and strengthened powers in the preservation of historic sites and buildings. The act also establishes an Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments to assist in the formulation of policies in connection with the work of the National Park Service.

LOCAL ADMINISTRATION

Each of the national parks is in charge of a local superintendent, who resides in the park and is responsible to regional and Washington headquarters for activities within the area under his control. In several of the smaller parks the superintendent has only four or five assistants. In the larger ones, such as the Yellowstone and the Yosemite, a large force is necessary, and includes protective, clerical, educational, and engineering assistants.

The protective work is done by the ranger force, headed by a chief ranger, who reports to the superintendent. The permanent ranger force is the all-year nucleus around which is built up the larger summer temporary force to handle the increased work of the tourist season. The permanent ranger positions are filled by civil service appointment. Ranger duties include checking travel, directing traffic, enforcing the rules and regulations promulgated by the Secretary of the Interior for the protection of the park, giving information to visitors, fire fighting, improvement of trails, repair of telephone lines, protection of wildlife, fish planting, supervision of campgrounds, and numerous other duties.

The national monuments are headed by superintendents or custodians. The group of 27 southwestern national monuments is in charge of a superintendent through whom the local custodians report. There are also several eastern groups of four or five historical areas under coordinating superintendents.

EDUCATIONAL USES

The national parks are veritable outdoor laboratories, offering unexcelled opportunities for informal education. The wealth of natural history and human history encountered in the Federal parks is interpreted by naturalists and historians. This service is a direct outgrowth of the interest displayed by visitors in the why and wherefore of the interesting and unusual things encountered along the beaten track or on the out-of-the-way trail.

The demand for knowledge is met primarily in two ways—through the naturalist and historian services and through the museums. The ranger naturalists and historians are trained in the natural sciences, history, or archeology, and in public contacts. They conduct parties out on the park trails on short or long trips and give informal talks at the campfires in the public auto camps, community houses, museums, and outdoor ampitheaters.

The museums in the wilderness national parks and monuments are designed primarily to interest the average visitor in finding out for himself just what the particular unit has to offer. It has been said that the museum exhibits are in reality only the index to the park or monument, which is the real museum of nature.

In the historical areas the museums contain relics and artifacts connected with the human events which transpired in them, and which by their importance in the pageant of our national history entitle the areas to the status of historic shrine.

So in our prehistoric monuments. There the museum exhibits include the implements in use a thousand years ago in grinding corn, and in other ordinary routine of life—a sandal or other bit of clothing or personal adornment, shreds of baskets, and pottery of many designs and colors.

WHAT THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS AND ENGINEERS DO

Congress in establishing the National Park Service outlined its function to be the preservation of the national parks, monuments, and other reservations assigned to its jurisdiction in their natural condition for the use and enjoyment of American citizens of all times.

Carrying out this mandate involves the serious responsibility of conserving the finest natural scenery the country has to offer and of guarding more than 21,500,000 acres of territory, at the same time making the parks and monuments accessible to the millions of visitors annually.

To keep the natural beauty of mountain, forest, lake, and waterfall unspoiled and yet within easy access of such a multitude of visitors is an interesting though often difficult problem. Quoting the landscape architects, upon whom devolves the responsibility for this phase of park activities, the reverse of the famous principle used by the ostrich generally is followed, for roads, trails, and buildings all should provide a maximum of scenic view, at the same time being as inconspicuous as possible themselves.

The landscape process begins with selecting locations which do not tear up the landscape or obtrude into important views. This is followed by a study of the design, which endeavors to use native materials and other architectural features that will harmonize the structure with its surroundings. The last phase of the problem is the placing of any plant materials necessary to cure unavoidable damage that may have resulted from the construction.

The range of national park landscape problems is highly interesting and diversified. It runs the gamut from dog kennels in Alaska to colonial plantations in Virginia, from adobe houses with cactus gardens in the Southwest to subarctic roadside plantings in Maine, and from lakeside hotels in Montana to hot-spring developments in Arkansas. And new problems continually arise.

The actual construction work generally devolves upon the engineers, and all studies of the physical problems of each park are made by the landscape men, the engineers, and the individual park superintendents, and in special cases of historical interest by the historians. When a general scheme of development has been decided upon, a so-called "master plan" is prepared by the landscape architects on which is charted an outline of all future construction work. Using this master plan as a guide, designs are then worked out for the individual items, such as roads, buildings, parking areas, bridges, trails, and numerous miscellaneous projects.

The supplying of adequate living accommodations for visitors is an important phase of national park development, especially in those parks handling from a hundred thousand to nearly half a million visitors annually. The National Park Service, in addition to providing roads and trails and the necessary buildings for carrying on the administration of the parks, also provides free public automobile camps. The main camps in the larger parks have all the modern improvements. Wherever available without injury to forests, firewood is furnished to visitors without charge.

Not so many years ago most motorists making use of these campgrounds carried their own equipment, pitched their own tents, and cooked their own meals. But the gradual change in the habits of motorists has brought about the introduction and expansion of housekeeping cabins and cafeteria service in many of the larger camps. Hotels, lodges, transportation facilities, and various types of store service are operated by private capital under close Government supervision, as are the housekeeping cabins and cafeterias in the public camps.

THE WILD ANIMALS IN THEIR NATURAL HABITAT

One of the most fascinating features of the national parks is the opportunity they afford visitors to meet face to face wild animals such as their pioneer forefathers encountered in moving westward from the Atlantic seaboard. In the comparatively short time of a few decades, these animals that were once plentiful on plains and mountains have almost disappeared. Today, there are few places where they can be seen, and of these the national parks take first rank.

The park visitors want animal stories, and more animal stories. One that always engenders keen interest is that of the buffalo. Some thirty-odd years ago this animal, which once roamed the plains of the West in countless numbers, had almost disappeared. A few were taken into the Yellowstone, formerly a natural range for these great beasts. These animals, and the little remnant of the original Yellowstone herds, were given protection, with the result that the new herd increased with great rapidity. Several years ago it reached a thousand head, the greatest number that the range can properly accommodate. Since then, it has been desirable to eliminate surplus animals and ship them to other parts of the park or to restock depleted ranges beyond the park boundaries. In this way herds also have been established at Wind Cave National Park, Colorado National Monument, Platt National Park, the Crow Indian Reservation, and other places.

While telling the story of the buffalo and of the traits and habits of the various other park animals, the naturalists always explain that the national parks and monuments are absolute wildlife sanctuaries. No hunting is permitted in any of them. The ban on killing, molesting, or feeding the wild creatures has, in effect, permitted them to lead their normal lives without dependence upon man (except protection from man himself). National parks are the only places on the North American continent where the wildlife may be observed in its free state unafraid of or completely ignoring the presence of man.

In relating the story of the Yellowstone buffalo, and also antelope— another plains animal that had almost disappeared—emphasis also is laid on the fact that no species of animal, or plant for that matter, not originally native to the area, is ever introduced into a national park with the possible exception of game fish.

Bears are a delight to the visitors, except to those who insist upon becoming familiar with them and are bitten or scratched in reproof. For protection of the bears as well as the visitors, park regulations prohibit feeding of the animals. Naturalists have found that bruin in his native haunts feeding upon his native foods is healthier and probably happier than the half-tame begging bears that once gorged on peanuts, bread, and sundry other foods in our national park. An old mother bear with cubs romping around her, majestically crossing a woodland glade, is a superb sight—far more thrilling than a dozen bears, rooting like pigs in a garbage dump.

In some places, bears are classified as predatory animals and hounded by hunters and trappers. But in our national parks where all wildlife is protected, the bears are found just as they were when the first intrepid white man wandered through the areas.

Glimpses of deer, elk, moose, antelope, and mountain sheep add much to the pleasure of a park trip. There are many smaller animals which provide much amusement, notably the little "picket pins," or ground squirrels that scurry about on their serious business of food getting, oblivious to the "giant" human beings watching them. For the bird lover also the parks are a paradise.

A bird conservation problem that now faces the National Park Service involves the trumpeter swan. This bird, practically extinct a few years ago, has recently found the Yellowstone region a favorable nesting place, and the National Park Service, in cooperation with the Fish and Wildlife Service, is doing everything possible to guard the breeding places and to protect the young birds until they become strong enough to fight their own battles. During the last few years a definite increase in the number of these swans has been noted, both in the Yellowstone and in the nearby Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge.

FISHING

Although hunting is strictly banned in the national parks, fishing is permitted under regulations that insure against depletion of the fish supply. No fishing licenses are required by the Federal Government, but State fishing licenses are required in all except Glacier, Crater Lake, Mount Rainier, Mount McKinley, and Yellowstone National Parks.

The waters of several of the parks contain excellent native game fish while others at the time of park establishment were practically barren. To insure good fishing, many millions of eyed eggs and fingerlings are planted each year in park lakes and streams through the cooperation of Federal and State fish hatcheries. Every effort is made to improve fishing conditions and afford good sport for the thousands of anglers who seek recreation in the parks.

The best fishing, of course, is in the lakes and streams away from the main motor roads. Even along the highways the fish are plentiful, but they are also accustomed to most forms of artificial bait, so that they become wary a fact which adds to the enjoyment of the skilled fisherman. Even the Grand Canyon, in Arizona's semidesert, is becoming of keen interest to anglers through the stocking of Bright Angel and several other creeks. The large fish hatcheries operated at Yellowstone Lake in Yellowstone National Park and at Happy Isles in Yosemite National Park are great attractions to visitors. Special guides take parties through at stated hours, and observation platforms and aquaria are so arranged that the entire operation may be easily studied.

The few regulations laid down by the National Park Service concerning fishing are all designed to aid fishing conditions. The number and size of fish that may be taken in any one day are limited, according to the supply in a particular body of water. Sometimes, to protect newly planted young fish or promote the comeback of an overfished lake or stream, fishing in particular waters is temporarily suspended.

For the convenience of fishermen who visit the various national parks, the stores in these reservations carry in stock and have on sale each season a large quantity of appropriate fishing tackle and other necessary equipment.

1 As of October 1, 1940.

Top

Top

Last Modified: Fri, Sep 1 2000 07:08:48 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/glimpses1/glimpses1.htm

![]()

I

I