MENU

|

| |

Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites by J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord, and R. Lord |

|

|

| |

Chapter 4

Gila River Relocation Center

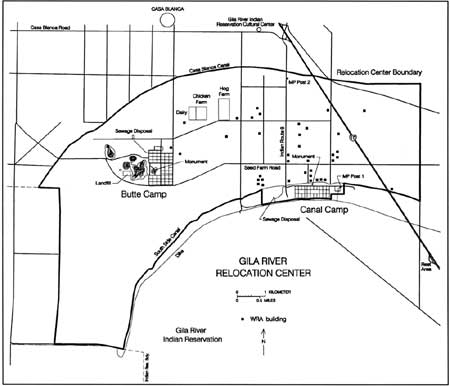

The Gila River Relocation Center was located about 50 miles south of Phoenix and 9 miles west of Sacaton in Pinal County, Arizona. The site is on the Gila River Indian Reservation, and access to the site today is restricted. The post office designation for the center was Rivers, named after Jim Rivers, the first Pima Indian killed in action during World War I. The relocation center included two separate camps located 3-1/2 miles apart, Canal Camp (originally called Camp No. 1) in the eastern half of the Relocation Center reserve, and Butte Camp (Camp No. 2) in the western half. When the Gila River Relocation Center was in operation it was the fourth largest city in Arizona, after Phoenix, Tucson, and the relocation center at Poston.

The Gila Relocation Center lies within the broad Gila River Valley, and the Gila River flows southeast to northwest about 4 miles northeast of the reserve boundary. Just 3 miles south of the reserve, the rocky Sacaton Mountains rise 700 feet above the valley floor. Two main irrigation canals roughly follow the contours of the Sacaton Mountains' north and east bajada, and most of the relocation center reserve lies between these two canals (Figure 4.1). The South Side Canal, at about 1350 feet elevation, is near the southern boundary; the Casa Blanca Canal, at about 1225 feet elevation, forms the northern boundary. Interstate 10 now cuts through the eastern portion of what once were farm fields of the reserve. Most of the relocation center is on flat or very gently sloping sandy alluvial loam, but the rocky outcroppings of Sacaton Butte are just west and north of Butte Camp. The Sonoran desert vegetation of the area is dominated by mesquite trees, creosote and bursage bushes, and cactus.

Figure 4.1 Gila River Relocation Center. (click image for larger size (~72K) ) |

The WRA leased the 16,500 acres for the relocation center reserve from the Bureau of Indian Affairs under a five-year permit. Under the terms of the permit, the WRA agreed to develop agricultural lands and build roads to connect the relocation center with state highways to the north and south. Construction of the relocation center began on May 1, 1942, with 125 workers; by June over 1,250 were employed (Weik 1992). On July 10, the first advance group of 500 Japanese Americans arrived to help set up the relocation center. Groups of 500 Japanese American started to arrive each day the following week. By August the evacuee population was over 8,000. The maximum population, 13,348, was reached in November 1942 even before major construction was completed, which was not until December 1, 1942.

Figure 4.2. Typical barracks at the Gila River Relocation Center. (National Archives photograph) |

The evacuee barracks at the two camps were constructed of wood frame and sheathed with lightweight white "beaverboard." Roofs were double, to provide protection from the heat of the desert, with the top roofs sheathed with red fireproof shingles (Figure 4.2). Another extra feature to help deal with the heat at the Gila River Relocation Center was the use of evaporative coolers. Clearly the Gila River Relocation Center was a showplace. Soon after his arrival at the center anthropologist Robert F. Spencer noted "The center is rather attractive as compared with the others. The white houses with their red roofs can be seen from miles away" (Spencer 1942). In April 1943, Eleanor Roosevelt, along with WRA director Dillon Meyer, made a surprise visit to the Gila River Relocation Center, spending 6 hours inspecting facilities (see Chapter 2; Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Eleanor Roosevelt at the Gila River Relocation Center, April 23, 1943. (Francis Stewart photograph, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley) |

Figure 4.4. Model ship building shop. (National Archives photograph) |

However, in spite of the model appearance of the camps, there were problems with the infrastructure. There were chronic water shortages, and for a time parts of Butte Camp ran out of water by nightfall. Use of evaporative coolers was curtailed and other water conservation measures were enforced. An existing natural gas line just east of Canal Camp provided fuel to heat the mess halls and hospital, but barracks were heated with fuel oil due to a limited supply of natural gas (Madden 1969).

Only one watch tower was ever erected at the Gila River Relocation Center. Located at Canal Camp, it was reportedly torn down because staffing it would have imposed a serious burden on the small military police detachment (Madden 1969). Within 6 months the perimeter barbed wire fences around each camp were removed as well. At Butte Camp a camouflage net factory run by Southern California Glass Company employed 500 evacuees. But, the factory was discontinued after 5 months. A model ship building shop at Canal Camp provided models for use in military training (Figure 4.4).

Supplies for the relocation center were originally shipped by train to Casa Grande and transported the last 17 miles to the camps by truck. In 1943 a loading and warehouse facility for the center was built at a railroad siding at Serape, only 11 miles away.

Top

Top

Last Modified: Fri, Sep 1 2000 07:08:48 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/anthropology74/ce4.htm

![]()