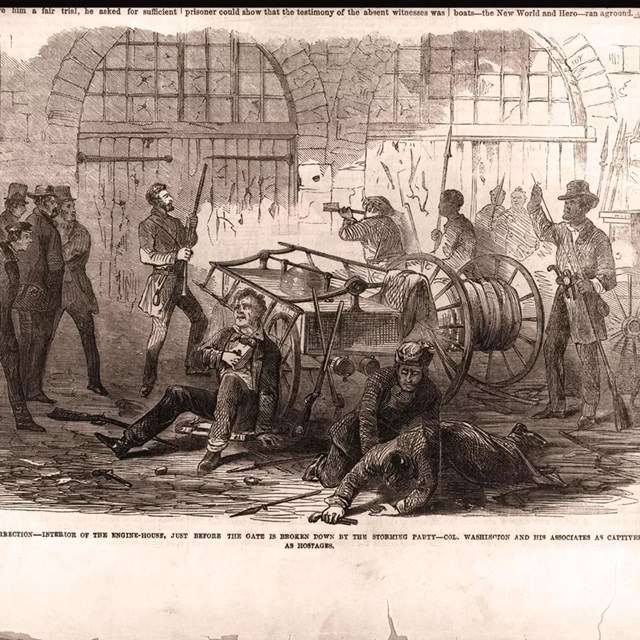

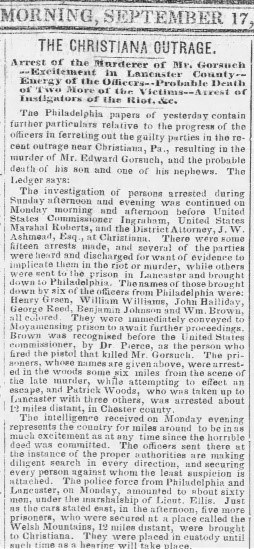

NPS The Road to WarIn the early 1850s, discussions amongst the Ridgely family, neighbors and guests in the mansion’s elegant drawing room probably revolved around subjects such as the Compromise of 1850, “property” rights of enslavers, the role of abolitionists and free Blacks, fears of uprisings by enslaved individuals, and the growth of sectionalism.

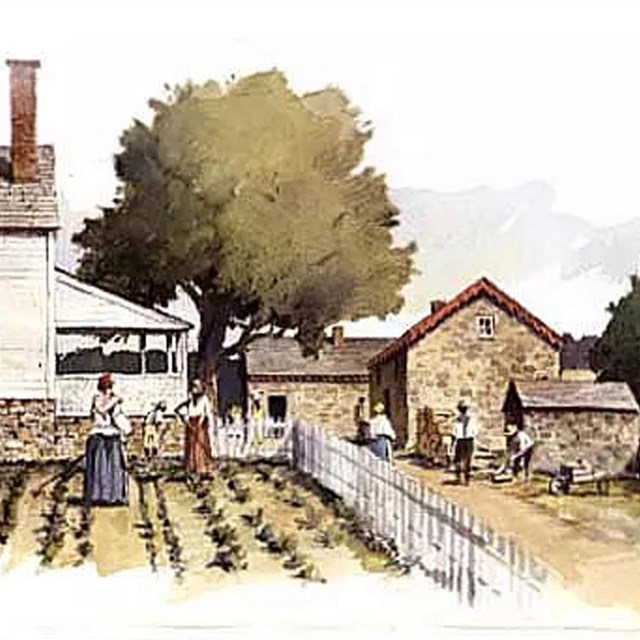

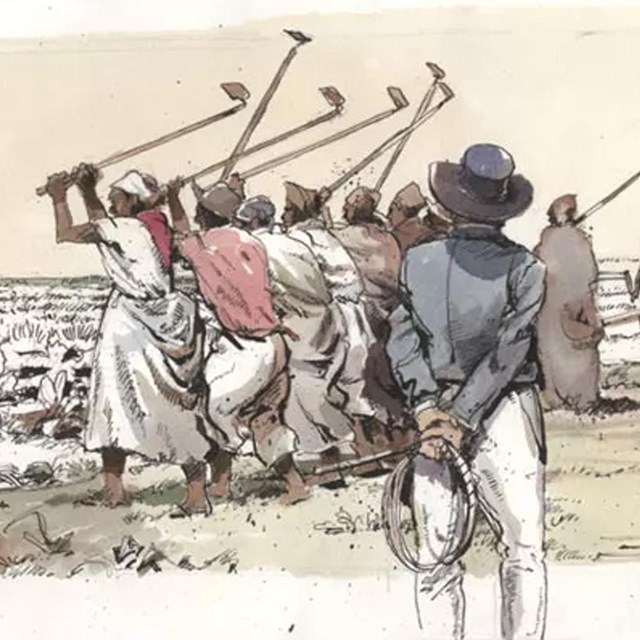

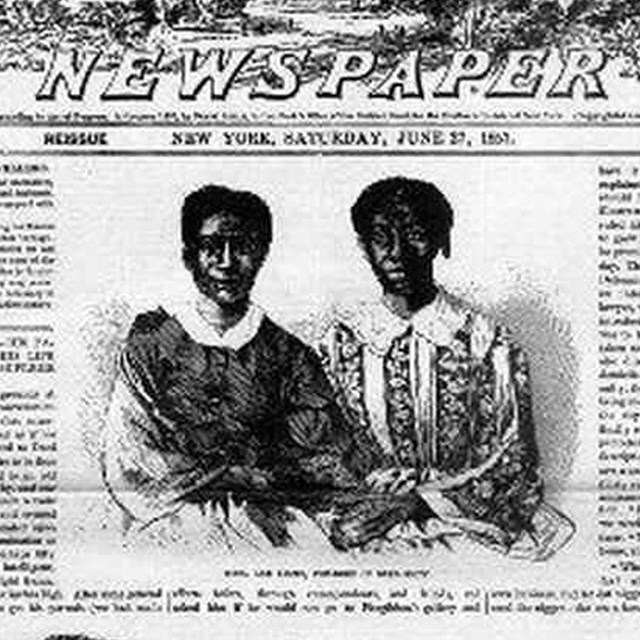

NPS Wartime HamptonOn the eve of the Civil War, the Hampton plantation covered over 4,000 acres and included over 60 enslaved persons and a few free Black laborers. “I have many memories of the Civil War,” John and Eliza Ridgely’s grandson Henry White recalled, “the greater part of them not very pleasant to one, who, even as a child, greatly disliked heated discussions between members of the family and friends.” During the course of the war, family members reported that they were torn between sympathy for the Confederacy, hinging on their continued embrace of slavery, and the fact that, in the words of White, the family maintained a “material interest dependent of Northern victory.” “Hardly a day passed,” he bitterly remembered, “that I did not hear one or more such discussions, during which the parties thereto frequently lost their tempers and ended…by not speaking to each other.” The Ridgelys feared that “Maryland would be a buffer state between the contending sections,” to say nothing of “the dread of confiscation and possible slave insurrection and rapine and murder.” War’s EndThe Civil War proved to be a defining moment in Hampton’s history. Although the three major military campaigns that came through the state of Maryland never reached Hampton, the battle fought on the plantation was one of culture, morality, and human rights. On multiple occasions large groups of enslaved people left Hampton during the war, and some of those who escaped went on to serve in the United States military helping ensure not only their own freedom, but also fighting for the freedom of others. In contrast, Charles Ridgely felt restrictions of freedoms with the suspension of Habeas Corpus in the state, being forced to be on house arrest, or face time in prison for his support of the Confederacy. In November of 1864 (just about five months before the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox) Maryland issued its emancipation of all enslaved people in the state. For Hampton their labor force was freed and those that wished to remain could do so as free paid laborers. This major change in the operations of Hampton began the road to the eventual economic decline of the estate. Individuals

Slavery at Hampton

More about Civil War

|

Last updated: March 18, 2024