Anchorage Museum of History and Art When many people think of Gates of the Arctic, they envision a vast, remote landscape with no sign of human presence. In fact, people have lived and travelled through this land for thousands of years. Because of a deal struck when the park was established, today the village of Anaktuvuk Pass exists within the boundaries of the park. The residents of Anaktuvuk Pass are nearly all Nunamiut, the mountain Eskimos who traditionally migrated on a seasonal path between the Brooks Range and the Arctic coast. These nomadic peoples had a diet and a lifestyle that revolved around the migrating herds of caribou on the North Slope. During the 1940s, life began to change for the Nunamiut. Contact with outsiders brought a reliable supply of guns, ammunition, and foodstuffs which the people acquired in trade for wolf hides and other furs. The pilot Sigurd Wien, after trading with the Nunamiut for some years, convinced the band at Chandler Lake to relocate to the Anaktuvuk Valley, promising improved air service and the possibility of schooling for the children. By 1949, the Nunamiut—consisting of five families from Chandler Lake, followed by eight families from the Killik River—moved to a plateau at the headwaters of the John River and founded the village of Anaktuvuk Pass. Before long the community had its own school, airstrip, and church.

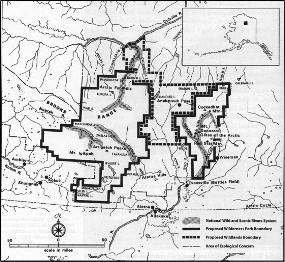

Bill Brown The National Park Service first began to consider a parkland in the central Brooks Range in the early 1960s, but it was not until 1968 that an NPS team surveyed the area and recommended a 4.1 million-acre, two-unit Gates of the Arctic National Park. The two units of this early proposal were drawn well away from Anaktuvuk Pass and the John River valley to the south. During the same period, petroleum discoveries on the North Slope inspired Governor Walter Hickel to carve an "ice road" out of the wilderness that ran through Anaktuvuk Pass and beyond to the oil fields. For six weeks after its completion in the winter of 1968–69, bulldozers and large trucks roared through the village and ended the community’s isolation in the blink of an eye. Subsequent NPS park proposals also avoided including the Eskimo village, and it was not until the early 1970s that local people began to recognize that designating their lands as a national park would buffer the community from outside development.

Anchorage Museum of History and Art With the understanding that the NPS would help to protect their subsistence resources, the Nunamiut Corporation (the newly established village corporation of Anaktuvuk Pass) and the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (the regional corporation encompassing the village) soon began to entertain the idea of a permanent dual-ownership arrangement. NPS and Native corporation officials considered a number of land-ownership and management plans, and when Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve was officially established in 1980, Anaktuvuk Pass and the surrounding lands were included as an inholding within the park boundary. The negotiations, however, had really just begun. After the park was established, NPS officials imposed a ban on all-terrain vehicle use on park lands. The six- and eight-wheeled vehicles known as Argos and other forms of motorized transport were becoming more popular with Anaktuvuk Pass residents, and the villagers chafed at restrictions that prevented them from gaining access to the wildlife on which they depended for food and limited their travel on traditional lands. Meanwhile, the NPS became increasingly concerned that the machines were disturbing the tundra and eroding wilderness values. In the late 1980s, a proposal for a three-way land exchange between the NPS, the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, and the Nunamiut Corporation evolved through lengthy negotiations and was finally passed in 1996. The result was a sizable contiguous section of Native lands and specific designated park lands that would allow the people of Anaktuvuk Pass to pursue their traditional harvest of subsistence foods.

NPS/Josh Spice |

Last updated: August 19, 2020