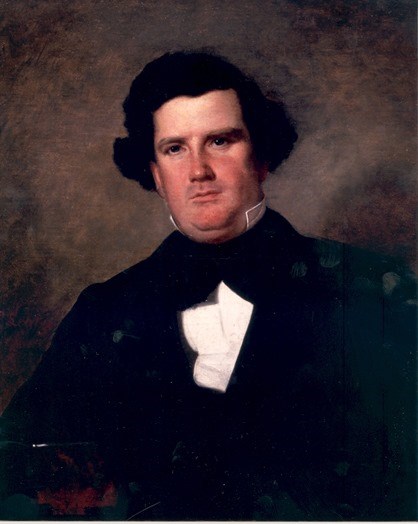

NPS Image By the outbreak of the Civil War, James Horace Lacy had established himself as one of the leading citizens of Fredericksburg society. In addition to a vast real estate portfolio and accumulated wealth, Lacy cultivated a reputation for speech making and community leadership. He served as a president or leader of many local commissions and societies, and was an outspoken supporter of Virginia secession. Within days of secession in 1861, Lacy was appointed to serve as aide-de-camp to Daniel Ruggles, with the title of Captain. This was not an official military commission or rank, but more an honorary title. Lacy passionately involved himself in the romantic drama of the early Civil War. He packed a picnic and journeyed to Manassas to watch the first major battle, calling to his wife as he left, "My dear, next week I will be making a speech from the steps of the Capitol in Washington!" As the war progressed, Lacy continued serving as an aide in Richmond, using the rank "Major", but without an official military commission. It was in this capacity that Lacy found himself delivering dispatches to General Robert E. Lee on the eve of the battle of Fredericksburg. Due to his orders, Lacy was unable to stay and observe the battle, but during his brief visit with the general, a great myth was born. Lacy reportedly gave permission to General Lee to fire on his home, Chatham Manor, if it was necessary for the Confederate cause. Lee refused, stating that the house had special significance as the spot where he courted his wife. This story is not corroborated in any other source outside of Lacy's account, and there is no evidence to indicate that Lee and his wife met at Chatham. Mary Custis Lee was the granddaughter of the original owners of Chatham, but the house had been sold out of the family long before her birth. It is likely that the memory of his interaction with Lee at Fredericksburg was blurred by romantic retellings of war stories and evolved into the family legend that lives today. Lacy's service throughout the rest of the war went on without great incident. He was briefly captured in September 1863 and spent four months at Ft. Delaware before being exchanged for another Union officer. He did finally receive an official military commission as a lieutenant, and served as a quartermaster in Mississippi through the rest the war. Lacy fell on hard times after the Civil War due in large part to the loss of his slaves. He was able to restore some of the family fortune by selling portions of his real estate holdings, but was never able to regain his pre-war prosperity. Despite the decline in fortune, Lacy enthusiastically took up the mantel of politics and the Lost Cause. He addressed the first meeting of the Ladies' Memorial Association of Fredericksburg in 1866, and was employed by the LMA to "represent the urgent need of the Association whenever and wherever he may think the cause would meet with sympathy and support." Lacy embarked on a speaking tour of Baltimore, New York and New Orleans in order to raise money for the Association. His efforts garnered $10,000 in pledges, which was applied to the purchase of land in Fredericksburg to create the Confederate Cemetery. Lacy's passion for speaking about the Confederate cause and memory was well known among the citizens of Fredericksburg, and his love for speech making continued to grow. During a meeting to discuss the establishment of a railroad commission, Lacy declared his intention to run for the office of railroad commissioner with an emotional description of his qualifications and post-war existence:

Although the sentiment behind this oration was widely held in the post-war South, it seems that Lacy's constant speech making exhausted the people of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania. In 1873 when Lacy ran for a seat in the House of Delegates, the Fredericksburg Ledger ran a series of editorials criticizing Lacy for his excessive speeches, calling him "the cave of winds". The Ledger argued further that Virginians paid $1200 a day for the legislature, and electing Lacy would cost taxpayers more money as he would take up days making lengthy speeches. "Don't send a man there who is more famous for speech-making than anything else." Lacy's race was quite close but he found an ally in the Fredericksburg News:

Lacy's contentious election came at a pivotal moment in Southern politics. Rebuilding the social structures of the antebellum era and creating strict barriers around the emancipated black population were the highest priorities of white legislators at this time. Lacy tapped in to the emotional drive behind these priorities and tailored his drawn-out oratory to appeal to those sentiments. In the end, voters agreed with the Fredericksburg News and elected Lacy to serve in the House of Delegates for one term. Unfortunately, Lacy's only successful legislative effort was to officially designate the North Anna River as a fence, or boundary between properties. J. Horace Lacy died in 1906. His political career, although often overshadowed by his extensive landholding and famous uses of his estates during the Civil War, was the primary characteristic of his post-war experience.

Text by Maureen Lavelle |

Last updated: July 24, 2016