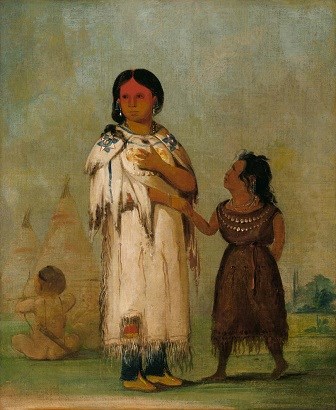

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM, 1985.66.181 Assiniboine OriginsAssiniboine, pronounced uh-SIN-uh-boin, comes from the Chippewa or Algonquian language family and means "those who cook with stones." This refers to stone boiling, the practice of heating stones directly in a fire and then placing them in water to boil it for cooking. British explorers and traders also used the name "Stoney" for the tribe. The Assiniboine term for themselves is "Nakodabi." Once white traders entered their territory, the Assiniboine bartered furs with both the French and English, receiving firearms, gunflints, ammunition, and other European trade goods such as jewelry, knives, pigments, brass kettles, wool blankets, and metal implements like iron projectile points. It was the Assiniboine who aided white contact with the Mandan. In 1738, French fur trader and explorer La Verendrye accompanied an Assiniboine trading party south from a post in Manitoba, reaching a Mandan earthlodge village in central North Dakota, near today's Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

NPS / FREDERICK MACVAUGH, FOUS 16835,70181, 94876, 16782, 32520, 83830,16885, 375, 2704, and 80228. Fort Union and the AssiniboineBy 1828, when Fort Union was established, the Assiniboine inhabited northwest North Dakota, northeast Montana, and southern Saskatchewan. Kenneth McKenzie, Fort Union's first bourgeois or post manager, received permission from the Assiniboine to establish a trading post in their midst. McKenzie parlayed this agreement with the Assiniboine on behalf of John Jacob Astor and his American Fur Company.

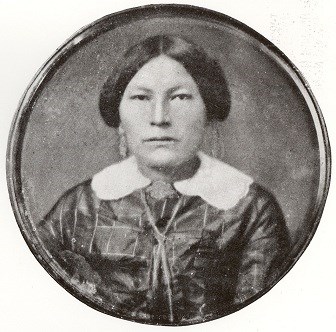

NPS - SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION IMAGE FROM THE FORTY-SIXTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY For some of their history, the Assiniboine allied with the Cree against the Blackfeet, who lived farther west on the Missouri River. No military post was established specifically to police the Assiniboine, and no American troops ever warred against them. Some Assiniboine worked as scouts for the military operating out of Fort Buford, the military post built three miles east of Fort Union in 1866 for the purpose of controlling the Confluence and protecting Montana-bound gold seekers. Assiniboine scouts in 1885 also assisted the Canadian North West Field Force in tracking down a group of mixed-blood people, the Métis, who rebelled in Canada. Smallpox TragedyIn 1837, tragedy struck the tribes on the Upper Missouri. The American Fur Company steamboat St. Peters arrived at Fort Union, inadvertently carrying an extremely virulent strain of smallpox. The disease reached the fort as a band of Assiniboine arrived to trade. The traders urged the people not to come, as the fort was a plague post, but they paid no heed. Other bands came as well and smallpox spread throughout the tribe. Before the disease, the Assiniboine numbered 10,000 people, a population the epidemic reduced at least by half.

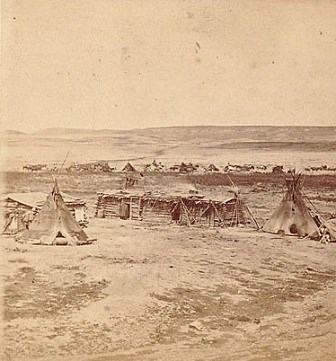

COURTESY OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION’S NATIONAL ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHIVES, NAA INV 09835800 / WILLIAM ILLINGWORTH AND JOHN CARBUTT In 1867, the U.S. Army purchased and dismantled Fort Union, using the salvaged materials—timber and stone—to aid in the expansion of Fort Buford, which lasted as a military post until 1895. In his memoir, Forty Years a Fur Trader on the Upper Missouri, Fort Union's final bourgeois and subsequent operator of a short-lived independent trading post, Charles Larpenteur, recalled the reaction of the Assiniboine chief Crazy Bear: "We cannot understand those whites. We had a good country, which we always thought they would save for us; they have given it to our enemies [the Sioux]. Fort Union, the house built for our fathers,—in the heart of our country,—the soldiers have pulled it down to build their Fort Buford, where we are scarcely permitted to enter." The Assiniboine TodayThe chemistry of the Upper Missouri had changed. In the 1870s, different bands of the Assiniboine settled on reservations on either side of the United States–Canada border. Today in Montana, the Assiniboine share the Fort Belknap Reservation with the Gros Ventres and the Fort Peck Reservation with the Sioux. In Saskatchewan, they share one reserve with the Sioux and another with the Chippewa and Cree. A third band resides on two other reserves in Saskatchewan. The Assiniboine people's contributions to American history and the success of Fort Union were many, and they deserve to be recognized and celebrated. To start, visit our page dedicated to Crazy Bear, the peace-seeker who for a time nearly everyone opposed. |

Last updated: April 24, 2021