NPS/R. Negele Shown a photograph of the Colima Warbler, the non-birder rarely understands the obsession with a nondescript, grey bird. Sure, it’s got a patch of yellow on its rear and a dollop of rust on its crown, but basically, it’s grey. The Colima Warbler isn’t big. It’s not flashy. But it’s a Big Bend specialty.

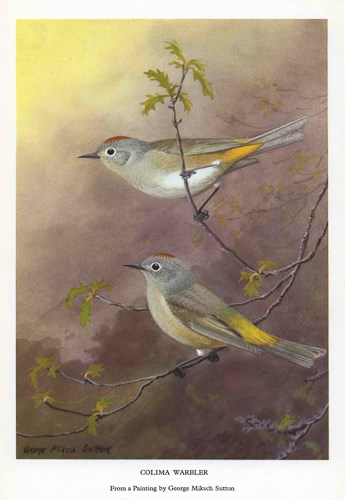

Original painting by George Miksch Sutton. Discovery of a Big Bend SpecialtyIn 1889, W.B. Richardson—a specimen collector for the American Museum of Natural History—discovered the Colima Warbler high in the Sierra Nevada de Colima in Mexico. For the next 39 years, ornithologists knew the bird existed, but that was about all they knew. The Colima Warbler remained a rare curiosity.On a warm, July day in 1928, that changed. Dr. Frederick M. Gaige, entomologist, herpetologist, and director of the Museum of Zoology at the University of Michigan, collected a male Colima Warbler in the oak woodland of Boot Canyon, high in the Chisos Mountains. The discovery pushed the range of the Colima Warbler to its northernmost extent. University of Michigan ornithologist Josselyn Van Tyne organized a second expedition to west Texas in the spring of 1932. Eight sturdy burros packed their field camp and supplies up the Juniper Canyon trail to Boot Canyon. At least one or two Colima Warblers sang from nearly every oak thicket. Van Tyne was thrilled to find the birds. But his primary objective was to learn about the Colima Warbler’s nesting behavior. As he walked along a dry creek bed, a female warbler with nest material in her mouth flew by.

NPS Photo A Nest is Found“I stopped instantly and, remaining motionless, was greatly relieved to see the warbler continue undisturbed by my presence. In a moment she dropped to the ground and entered the nest which was on the sloping right bank of the stream about six feet back from the margin of the rocky stream bed. After working for about 20 seconds the warbler left the nest and flew down the stream bed… .” (Van Tyne 1936)The nests are simple, symmetrical cups, woven from rootlets and fine grass material. Tucked under a rock, concealed by an arch of grasses, or covered by dry leaves, Colima Warbler nests are well-hidden from predators and observers. Finding active, nesting birds convinced Van Tyne that the Colima Warblers weren’t stray birds. The oak, maple, and Arizona cypress woodlands of the high Chisos was prime breeding territory. The population of Colima Warblers in Big Bend is relatively stable. Every 5 years, since 1967, up to 35 citizen scientists shoulder their packs and spread out in territories from Green Gulch to Boot Canyon to search for warblers. Numbers fluctuate, but the Colimas are still there, year after year. 5 Tips for a Successful Colima Warbler SearchOrnithologists have searched for the Colima Warbler in other sky islands of the southwest. But so far, the only place to see this bird is in Big Bend National Park. Here are some tips for adding the Colima Warbler to your life list:

CitationVan Tyne, J. 1936. The Discovery of the Nest of the Colima Warbler (Vermivora crissalis). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Miscellaneous Publications No. 33.Bird Information

|

Last updated: May 31, 2020