Last updated: December 5, 2023

Lesson Plan

The Shields-Ethridge Farm: The End of a Way of Life

- Grade Level:

- Middle School: Sixth Grade through Eighth Grade

- Subject:

- Literacy and Language Arts,Social Studies

- Lesson Duration:

- 90 Minutes

- Common Core Standards:

- 6-8.RH.2, 6-8.RH.3, 6-8.RH.4, 6-8.RH.5, 6-8.RH.6, 6-8.RH.7, 6-8.RH.8, 6-8.RH.9, 6-8.RH.10, 9-10.RH.1, 9-10.RH.2, 9-10.RH.3, 9-10.RH.4, 9-10.RH.5, 9-10.RH.6, 9-10.RH.7, 9-10.RH.8, 9-10.RH.9, 9-10.RH.10

- Additional Standards:

- US History Era 7 Standard 1B: The student understands Progressivism at the national level.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies from the National Council for the Social Studies

Essential Question

Learn about the role cotton farming played in the South after the Civil War and how African Americans shaped the economic landscape.

Objective

1. To describe the role cotton farming played in the South after the Civil War;

2. To explain the work sharecroppers did throughout the year to produce a cotton crop;

3. To identify some of the factors that brought about the end of the sharecropping system in upland Georgia;

4. To research agricultural change in the local community and to plan an exhibit based on such research.

Background

Time Period: 1900-1940

Topics: This lesson could be used in units on the transformation of agriculture in the United States; the era of the Great Depression; and the impact of the New Deal on farms in the southern United States.

Preparation

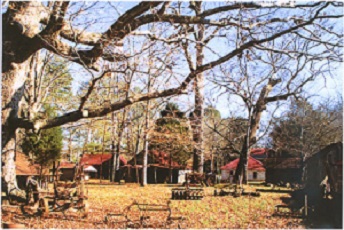

“What is that?" A ghost village appears on a drive through northeast Georgia. The collection of gray buildings with red tin roofs of peculiar sizes and shapes beckons. Should you stop and read more about the Shields-Ethridge Heritage Farm, you may imagine the ghost fields of cotton that once grew around these abandoned buildings. You may conjure the click of wagons, coming along the same road you drove, bringing cotton to the gin. You may even think you smell sausage being cooked after hog butchering.This was once a sharecropper’s village, where the seasons of planting and ginning cotton determined the way of life for fifty years.

The story of this place is the story of Ira Washington Ethridge, an entrepreneur who guided the farm through an agricultural revolution. It is also the story of sharecroppers, who in exchange for a house, cotton seed, and fertilizer, planted and picked cotton and paid the Ethridges a share of their crop. Today the cotton gin is quiet. The commissary, where sharecroppers could buy supplies, looks as if someone just closed and locked the door. Hoes, oxen yoke, and ploughs rust in the blacksmith's shop.

What froze this place in time? What clues tell the history of this place? Let's begin the story. Never mind the din of the helicopter overhead. Those are land prospectors, looking for green space to buy and subdivide. But we have time to explore. The history of a harsh and sometimes heroic existence can be read from the buildings and landscape on the Shields-Ethridge Farm.

Lesson Hook/Preview

The history of the Shields-Ethridge Farm is tied to cotton. This crop was in great demand in 1810, when Joseph Shields began growing “upland” cotton, the type of cotton grown most in the United States. The fertile land along Walnut Fork of the Oconee River had been cleared in 1790, when Shields and his sons bought 200 acres in what is now Jackson County, Georgia.

Cotton was and is the most important vegetable fiber used in producing textiles. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made it practical to grow cotton in the Piedmont section of Georgia (the area between the state’s Coastal Plain and the Appalachian Mountains). The gin could clean the heavily-seeded upland cotton much faster than human hands. By 1804, the South’s production of cotton was eight times greater than it had been in the previous decade. By 1860, textile mills in the North imported all of their cotton from the South. The southern production of cotton was also being consumed overseas by England and France who received more than three-fourths of their cotton supply from the American South.

Cotton farmers like Joseph Shields and his sons had enough land to benefit from this suddenly profitable crop for the next 50 years. They also had the second requirement for productivity: labor. By 1860 the Shields owned 20 slaves to plow, plant, and harvest the cotton. The Shields increased their land holdings to 496 acres by 1860.

Before the Civil War, Georgia was one of the leading cotton producers in the United States, but the war changed the cotton industry. The Shields farm produced a small quantity of cotton prior to the Civil War, but when the war ended, both sons returned to Georgia to rebuild the farm and concentrate on cotton production.

The war devastated the economy of the former Confederate states. Due to the emancipation of slavery, former black slaves had farm labor to offer, but did not have the funds to buy their own farmland. Many destitute white farmers also found themselves in this predicament. White, southern farm owners had the land and supplies to continue their production, but were without the necessary labor. Sharecropping was formed as a solution to this problem. When the farm owner and the laborer entered into a sharecropping contract, the farm owner agreed to lend the laborer farm land and supplies, but the laborer would then owe the farm owner a percentage of his crop. Many of the laborers who joined the sharecropping system ended up in a continuous cycle of debt and were therefore, tied to the land and the farm owner until they could pay off their debt.

Reconstruction in Jackson County meant rebuilding the capacity to produce cotton. The Shields faced two problems: repairing the cotton fields and finding field labor. For the Shields, the sharecropper system was the solution. Many former slaves continued to work on the Shields farm after the Civil War alongside poor white farmers who also sharecropped for the Shields. Under this system, the Shields brothers did well for the next 30 years. More land was acquired, and by 1890, the farm had grown to 1000 acres.

Robert Shields, grandson of Joseph Shields, inherited the family residence, which had been built in 1866 from hand hewn heart pine. Robert’s daughter, Susan Ella, and her husband, Ira Washington Ethridge, moved in to care for Robert in 1896. When Susan Ella’s father died in 1910, the home place and 114 acres were deeded to Susan Ella and Ira. The name “Ethridge” was now added to the farm, whose future was still tied to the cotton trade. Cotton still ruled the south, but prices for cotton fluctuated so wildly that cotton was called a “gambler’s trade.” Ira Washington Ethridge would gamble on cotton during the next 40 years, but he also “hedged his bets” by building a village to withstand the fickle cotton economy. It was a sharecroppers’ village, and all the structures built by 1920, except for some tenant houses, are still intact at the Shields-Ethridge Heritage Farm.

Procedure

Getting Started Prompt

Map: Orients the students and encourages them to think about how place affects culture and society

Readings: Primary and secondary source readings provide content and spark critical analysis.

Visual Evidence: Students critique and analyze visual evidence to tackle questions and support their own theories about the subject.

Optional post-lesson activities: If time allows, these will deepen your students' engagement with the topics and themes introduced in the lesson, and to help them develop essential skills.

Vocabulary

New Deal

Sharecropping

Cotton gin

Additional Resources

Booker T. Washington Papers

The University of Illinois houses the Booker T. Washington Papers, in which he discusses “white mud” (kaolin), recognizing its worth to the South. Read his May, 1911 account of the usefulness of this “native kalsomine” which is found on the Shields-Ethridge Farm, part of a vein in northeast Georgia.

FDR Speech on the Agricultural Adjustment Act, 1935

PBS's "American Experience" provides a transcription of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s address on the Agricultural Adjustment Act, May 14, 1935. Roosevelt reviews the plight of farmers and the plan to adjust crop production.

GA Historic Preservation Division: Agriculture

The Historic Preservation division of Georgia Department of Natural Resources presents the agricultural heritage of Georgia. This resource includes information about landscapes, buildings, and an inventory of Centennial Farms on the National Register in Georgia. Several scenes from the Shields-Ethridge Farm are shown.

Photo Dossier on Sharecropping

A photographic dossier of sharecropping during the years 1935-1939 in several southern states is posted on this Indiana University website. Sharecroppers’ houses and work life are captured in the photographs.

Shields-Ethridge Heritage Farm

The official website of the Shields-Ethridge Farm provides in-depth content about the family members, historic buildings, agriculture, and history of the farm. The site also has information about visiting the farm in small or large groups, with the farm's mobile app, or for public events.

University of Illinois essays on sharecropping

The Modern American Poetry website treats sharecropping as a theme in American literature, referring students to numerous authors who wrote about the sharecropping experience. Writers included in the synopsis present another point of view from sharecroppers’ accounts on the Shields-Ethridge Farm.

Vanishing Georgia Photographic Collection

The Georgia Division of Archives and History houses the “Vanishing Georgia” photographic collection of 18,000 historically significant photos. By searching the index for “sharecropper” or “cotton farming” the reader can view photographs taken in Georgia during the relevant time period.

World of the Tenant Farmer

The Texas Beyond History website contains a unit in its curriculum called “The World of A Tenant Farmer.” Photographs of cotton, of tenant farmers, and of artifacts from the 1920s on the Osborn Farm are included. Interviews with tenant farmers, many Mexican, describe the daily life of the workers.