Annie Ross

Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Indigenous Science, Archaeology and ‘Truth’

By: Annie Ross, Ph.D.

School of Social Science

The University of Queensland

Brisbane 4072 QLD

Australia

June 27, 2019

In 2018, my colleague, George Nicholas, wrote a Guest Column for the U.S. National Park Service as a response to some negative comments on another article he had written to further argue that Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a legitimate way of knowing about natural resources management. He argued against the criticism that any management approach that applies Indigenous knowledge as a valid management tool is ‘anti-science,’ ‘Left[wing] idiocy’ and ‘riddled with fallacies and misunderstandings.1 The vehemence of the critique Nicholas received did not surprise me. The call for TEK to be ‘approved’ and ‘supported’ by western science is not new.2 However, there is a growing body of evidence in the archaeological record for the longevity of TEK. Although I am not of the view that Indigenous people need to have their knowledge validated by western science, I think it is interesting that, when those of us trained in a western scientific paradigm do recognise the value of Indigenous oral testimony, it often challenges our stereotypes in new and important ways which can lead to revisions to standard interpretations. In this paper, I review the evidence for TEK as ‘science’ and provide some examples of the scientific ‘testing’ of TEK that have led to reconsiderations of the science rather than reconsiderations of the Indigenous ways of knowing.

Situating this perspective

I am an archaeologist by training. For 35 years I have worked with Aboriginal Australians, documenting their heritage and acquiring knowledge about their attachment to Country (the land and waters that make up their homelands). I have undertaken archaeological surveys and excavations, but mostly I have spent time listening to Elders and knowledgeable people telling me about their ancestral Law and lore relating to managing the resources of the land, the sea, the lakes and the rivers. It is these conversations that have informed and shaped my knowledge, and that have challenged my scientific paradigms.3

Indigenous knowledge and science

Aboriginal people have been taking care of the land and waters of the Australian continent since the Dreaming, when Ancestral Creator Beings made the world and filled it with people. According to Aboriginal Australians they have lived on the Australian continent ‘since the beginning of time’, contrasting with archaeological evidence that dates the first human arrival in Australia to around 65,000 years ago.4 There are many stories that tell of the ways the world was made and of the Laws assigned to people who were given the right and the responsibility to manage creation. The knowledge that Aboriginal people bring to land and sea management comes from the lore of the Dreaming and the accompanying Law handed down by Creator Beings. The Law sets out the principles of natural resources management. For Aboriginal people in southeastern Queensland, where I live, the Law is entangled with kinship relationships.

Uncle Denis Moreton, a Dandrabin-Gorenpul Elder, tells the story of the creation of North Stradbroke Island in Moreton Bay.5 According to Dandrabin-Gorenpul knowledge, Creator Beings made Law for the land, the sea, the animals and the people. The first people learned the Law from the creators. One such story relates to the relationship between the natural features of the land. The sand dunes of the island are male. The rain falling onto the dunes is sperm (moothie), which flows into the lakes (female) and gives life to all the plants and animals of the land. If the dunes are removed (for example by sand mining – the dominant industry on North Stradbroke Island) the cycle of life is broken.

The area occupied by Dandrabin-Gorenpul people is known as Quandamooka. The Dandrabin-Gorenpul people of Quandamooka today are the descendants of the Creator Beings and therefore, they have a close connection to all the ecosystems of Moreton Bay, as these ecosystems are the habitats of their ancestors. Dandrabin-Gorenpul people have a responsibility to keep the Law of their ancestors and to manage the land and waters of the bay in accordance with the Law.

The Dandrabin-Gorenpul people of Moreton Bay are linked to their Country — the land, sea and waters of the bay and islands — by ‘yurees.’ Each person is assigned specific plant or animal yurees depending on their kinship relationships and levels of knowledge of Law. Over time, a person will accumulate several different yurees, assigned at different periods in his/her life, such as at birth and at other special times related to rites of passage. When a person receives a yuree, that person (along with all other people who have been assigned the same yuree) becomes responsible for taking care of that yuree. The knowledge of the yuree and its habitats comes from the intellectual property rights that are inherited along with the yuree, and the knowledge of yuree management that is passed from one generation to the next by knowledgeable Elders. In this way Dandrabin-Gorenpul Law ensures the sustainable management of all the resources and habitats of the Moreton Bay region.

The assignment of yurees and the enactment of yuree rights and responsibilities continues today, albeit often in ways that are now limited by western legal impositions. For example, the people of Quandamooka are working with the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service to co-manage National Parks on North Stradbroke Island and Marine Parks in Moreton Bay. Aboriginal Knowledge is used to ensure sustainable bag limits for shellfish collection off beaches and for recreational fishers in the bay. Additionally, Dandrabin-Gorenpul holders of fire management knowledge advise government bushfire services on how and when fuel reduction burns should take place.

The use of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in this way can, at times, be challenging for western-trained scientists. Nevertheless, TEK is Indigenous Science. Science is not always conducted in laboratories using chemicals and complex machinery. We in the west think of science as objective; ‘knowledge without a knower.’ This concept of science is foreign to Indigenous peoples for whom knowledge is very much personalised and social, even spiritual in its construction. As a consequence, western scientific knowledge and Indigenous ways of knowing are often deemed to be distinctive modes of thought. But even western science had its beginnings in spiritual beliefs.

In the Bible, when God created the first human, Adam, God gave him all knowledge except for the Knowledge of Good and Evil.6 When first Eve, then Adam ate the apple from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, God not only banished them from the Garden of Eden, He also took away all Adam’s knowledge. In the 17th century, philosophers began a quest to re-learn all the knowledge that God had taken from Adam, and especially the knowledge given to Adam regarding how to care for the natural order of things. And so science emerged in western thought, with an emphasis on observations to discover the laws of nature. In many ways, this search for knowledge based on natural laws and observations of natural processes is similar to Indigenous ways of applying the Law, given to them by the Creator Beings and reinforced through knowledge structures such as the yuree system, to the management of the environment.

Certainly there are differences between western science and TEK, although neither is superior to the other. Western science is compartmentalised, with experts knowing a lot about a very specialised research area; knowledge is based on empirical observations and objective research; replicable experiments conducted in controlled situations are used to develop universal truths; and research results are published in learned, erudite journals. TEK is different. Although there are TEK experts in many Indigenous societies, knowledge is generally shared throughout the community; empirical observations are important, but the role of spirits in watching over knowledge holders to make sure the Law is upheld is also regarded as important; truths are locally based and supported by narratives of creation (in Australia this is termed ‘the Dreaming’); and knowledge is passed on through story, song and dance. The roles of spirit beings, Law, and social/kinship relationships are central to the conduct and the transmission of TEK throughout Aboriginal Australia and in many other Indigenous societies around the world. Yet despite these differences, there are also many similarities between western science and TEK. Both western science and Indigenous science involve understanding the world in which we live. Both seek to learn the best ways to take care of the earth’s ecosystems, and both are keen to ensure that knowledge is shared so that it continues into the future.

Archaeology, Palynology, and TEK

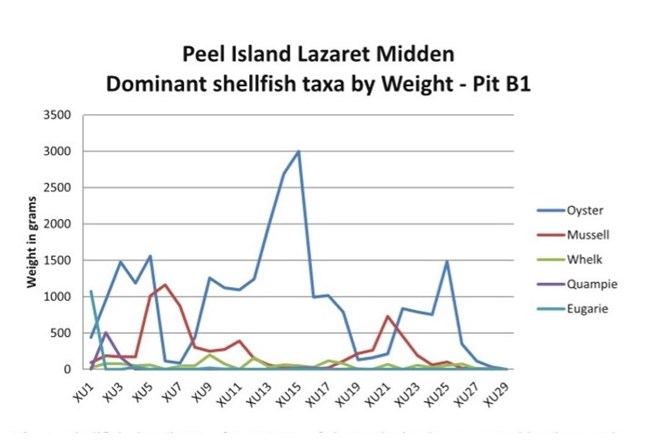

Archaeological and other scientific evidence, particularly evidence from pollen cores (palynology) indicates that TEK has been practised around the world for very long periods of time. Much of the evidence in Australia relates to maritime resources management. On Peel Island in Moreton Bay, where I have conducted research alongside Traditional Owners, we have found evidence for oyster shell discard that is indicative of oyster management in the bay that extends back more than 1000 years.7

Interpretations of the results of the excavation of the Lazaret Shell Midden on Peel Island were based on Indigenous Knowledge of oyster management, rather than the usual scientific explanations for the variation seen in the discard rates of oysters compared to other available shellfish species (Figure 1). Normally, archaeological interpretations for discard patterns such as these would argue that oysters had been over-exploited and, as their abundance declined, oysters were replaced by other species until the natural cycle allowed oysters to build up their numbers again; or that violent storms or climate variation caused oyster beds to be destroyed, forcing people onto secondary resources. But because my students and I were working with Traditional Owners and knowledge holders, we were able to re-evaluate that interpretation and develop a very different understanding of the shell midden, based on Dandrabin-Gorenpul TEK, as I now outline.

by weight.

Annie Ross

There is considerable other archaeological evidence for resources management such as that seen on Peel Island. Clam gardens on Quadra Island off the coast of Vancouver Island, Canada, are over 3,500 years old. Here, First Nations Canadians built artificial rock gardens to trap clams and encourage a managed growing environment for this important subsistence resource.8 On Mabuiag Island in the Torres Strait, northern Australia, Indigenous people have been hunting dugongs sustainably at a rate of 35-40 dugongs annually for over 500 years. Here, huge mounds of bone have been excavated by archaeologists working with Traditional Owners. As well as evidence for the hunting of dugong shown in these mounds, the researchers have found evidence for increase magic – a special form of ritual to encourage the spirits of dugongs to proliferate and ensure the longevity of the species.9 This evidence has helped Torres Strait Islanders and other Indigenous dugong hunters in Australia to argue that it is not their hunting of dugongs that has brought about the decline in dugong numbers over the past several decades, but poor land management by modern farmers. Western-trained scientists now recognise that land clearing and the resultant run-off into the seas destroys the sea grass beds that dugongs require, and that this is indeed the major cause of dugong decline.10 Legislation and government policy to manage dugong numbers now focuses on land management activity rather than limiting dugong hunting, at least in part as a consequence of engaging with Indigenous natural resources Law holders.

Fire management is another example of the role of TEK in modern land management policy and practice. Evidence from pollen cores demonstrates that Aboriginal Australians have been using fire to manage flora and fauna across the continent for tens of thousands of years. Anthropogenic burning increases biodiversity and prevents habitat loss, so it is a vitally important part of applied TEK in Australia. The correct use of fire can ensure the sustainable harvest of a range of plants and animals. Pollen evidence and charcoal particle analysis from a number of deep lakes around Australia shows that vegetation change and increased fire intensity are the results of anthropogenic fire management systems (known as ‘fire-stick farming’11) that have been a part of the Australian landscape for at least 21,000 years and possibly for long before this time. Recent research suggests that the most intense period of Aboriginal burning began about 16,000 years ago and continued until the arrival of European settlers interrupted the Aboriginal fire regime.12

Today, many parts of Australia continue to require regular hazard reduction burning to reduce fuel loads and to protect property from wildfire. Although the presence of houses and farms has necessitated firing practices that differ somewhat from traditional burning regimes, many of the principles of hazard reduction burning used by Aboriginal fire managers, particularly those relating to the timing of burning and the implementation of mosaic burns to ensure faunal species management, are now part of modern fire policy.

Returning to Moreton Bay, my final case study from Quandamooka has little outside, scientific evidence to support the TEK, but because there is so much ‘validation’ of Dandrabin-Gorenpul knowledge from archaeology, I think it is time to accept the Aboriginal knowledge for what it is. This is the story of mullet fishing in Moreton Bay.

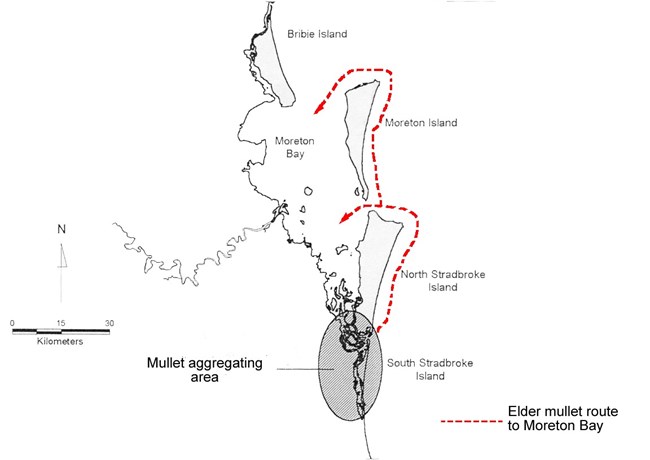

We know from archaeological evidence that the people of Quandamooka have been fishing for mullet for thousands of years. Unlike fisheries law in the west, Quandamooka Law states that the big fish must not be caught as the mullet commence their spawning run. The big fish are the Elders of the mullet society. They know the mullet Law and must teach that Law to the juvenile mullet. The Elders lead the mullet run and ensure the school turns west into the bay.

Annie Ross

In pre-contact times, it was only once the entire school reached the sheltered waters inside Moreton Bay that the main mullet fishing occurred. Until then, only the young or small fish were taken. But inside the bay, Aboriginal fishers would call out to their kin, the dolphins, who would drive the fish towards the shore where the fisherfolk were waiting with their huge nets. Large quantities of mullet were caught in the nets. The largest mullet were fed to the dolphins as a reward for their role in the fishing, and the abundant resource was shared during ceremonies held for Aboriginal people from all over southeast Queensland.

Today there is a large commercial mullet fishery outside Moreton Bay. The commercial fishers follow western law that allows only fish greater than a certain size to be caught. As a result, there is now a very small mullet population inside Moreton Bay. Most of the mullet Elders no longer know the route into the bay, and the mullet fishery is in serious decline. If only the western fisheries scientists had listened to the Aboriginal knowledge-holders in their management planning for the Moreton Bay fishery!

Conclusion

Aboriginal people have been using traditional ecosystems knowledge to ensure sustainable land and sea management for millennia. Their science may not always be presented in ways western scientists understand, but the outcome has been a sustainable natural resource management regime that lasted for millennia before the arrival of Europeans and continues in some areas today. My research echoes that of George Nicholas. It is time for Indigenous and western scientists to work together, to recognise each others’ values, for the long-term future of our shared planet.

Recommended reading

R. Bliege Bird, D. W. Bird, B. F. Codding, C. H. Parker, and J.H. Jones 2008 The “fire stick farming” hypothesis: Australian Aboriginal foraging strategies, biodiversity, and anthropogenic fire mosaics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA) 105 (39): 14796-14801

S.D. Mooney, S.P. Harrison, P.J. Bartlein. A.L. Daniau, J. Stevenson, K.C. Brownlie, S. Buckman, M. Cupper, J. Luly, M. Black and E. Colhoun2011 Late Quaternary fire regimes of Australasia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30(1-2): 28-46.

I.J. McNiven and A.C. Bedingfield 2008 Past and present marine mammal hunting rates and abundances: dugong (Dugong dugon) evidence from Dabangai Bone Mound, Torres Strait. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(2): 505-515.

I.J. McNiven and R. Feldman, R. 2003 Ritually orchestrated seascapes: hunting magic and dugong bone mounds in Torres Strait, NE Australia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 13(2): 169 - 194.

G. Nicholas and N.M. Markey 2015 Traditional knowledge, archaeological evidence, and other ways of knowing. Material culture as evidence: Best practices and exemplary cases in archaeology, pp.287-307.

A. Ross, S. Coghill, S. and B. Coghill 2015 Discarding the evidence: The place of natural resources stewardship in the creation of the Peel Island Lazaret Midden, Moreton Bay, southeast Queensland. Quaternary International, 385: 177-190.

A. Ross, K. Pickering-Sherman, J.G. Snodgrass, H.D. Delcore and R. Sherman 2011. Indigenous Peoples and the Collaborative Stewardship of Nature: Knowledge Binds and Institutional Conflicts. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

N.F. Smith, D. Lepofsky, G. Toniello, K. Holmes, L. Wilson, C.M. Neudorf et al. 2019 3,500 years of shellfish mariculture on the Northwest Coast of North America. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0211194.

Footnotes

1 G. Nicholas 2018 Converging or Contradictory Ways of Knowing: Assessing the Scientific Nature of Traditional Knowledge. Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Guest Column. U.S. National Parks Service. See also G. Nicholas and N.M. Markey 2015 Traditional knowledge, archaeological evidence, and other ways of knowing. Material culture as evidence: Best practices and exemplary cases in archaeology, pp.287-307.

2 For example: McGhee, R. 2008. Aboriginalism and the problems of indigenous archaeology. American Antiquity 73 (4), 579-597; Rowland, M.J. 2004 ‘Return of the noble savage’: misrepresenting the past, present and future. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2004 Issue 2, 2-14; Stump, D. 2013 On applied archaeology, indigenous knowledge, and the usable past. Current Anthropology 54 (3), 268-298.

3 A. Ross, K. Pickering-Sherman, J.G. Snodgrass, H.D. Delcore and R. Sherman 2011 Indigenous Peoples and the Collaborative Stewardship of Nature: Knowledge Binds and Institutional Conflicts. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

4 Clarkson, C., Smith, M., Marwick, B., Fullagar, R., Wallis, L.A., Faulkner, P., Manne, T., Hayes, E., Roberts, R.G., Jacobs, Z. and Carah, X., 2015. The archaeology, chronology and stratigraphy of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II): A site in northern Australia with early occupation. Journal of Human Evolution, 83, pp.46-64. Veth, P., Ward, I., Manne, T., Ulm, S., Ditchfield, K., Dortch, J., Hook, F., Petchey, F., Hogg, A., Questiaux, D. and Demuro, M., 2017. Early human occupation of a maritime desert, Barrow Island, North-West Australia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 168, pp.19-29.

5 Moreton, D., Ross, A., 2011. Gorenpul-Dandrabin knowledge of Moreton Bay. In: Davie, P. (Ed.), Wild Guide to Moreton Bay, second ed. Queensland Museum, Brisbane, pp. 58-67.

6 Harrison, P. 2007 The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

7 A. Ross, S. Coghill, S. and B. Coghill 2015 Discarding the evidence: The place of natural resources stewardship in the creation of the Peel Island Lazaret Midden, Moreton Bay, southeast Queensland. Quaternary International, 385: 177-190.

8 N.F. Smith, D. Lepofsky, G. Toniello, K. Holmes, L. Wilson, C.M. Neudorf et al. 2019 3,500 years of shellfish mariculture on the Northwest Coast of North America. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0211194.

9 I.J. McNiven and A.C. Bedingfield 2008 Past and present marine mammal hunting rates and abundances: dugong (Dugong dugon) evidence from Dabangai Bone Mound, Torres Strait. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(2): 505-515; see also I.J. McNiven and R. Feldman, R. 2003 Ritually orchestrated seascapes: hunting magic and dugong bone mounds in Torres Strait, NE Australia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 13(2): 169 - 194.

10 T.P. Hughes, J.C. Day and J. Brodie 2015 Securing the future of the Great Barrier Reef. Nature Climate Change 5: 508-511.

11 R. Jones, 1969. Fire-stick farming. Australian Natural History, 16(7): 224-228.

12 R. Bliege Bird, D. W. Bird, B. F. Codding, C. H. Parker, and J.H. Jones 2008 The “fire stick farming” hypothesis: Australian Aboriginal foraging strategies, biodiversity, and anthropogenic fire mosaics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA) 105 (39): 14796-14801; see also S.D. Mooney, S.P. Harrison, P.J. Bartlein. A.L. Daniau, J. Stevenson, K.C. Brownlie, S. Buckman, M. Cupper, J. Luly, M. Black and E. Colhoun2011 Late Quaternary fire regimes of Australasia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30(1-2): 28-46.

Last updated: June 27, 2019