Julie West / NPS

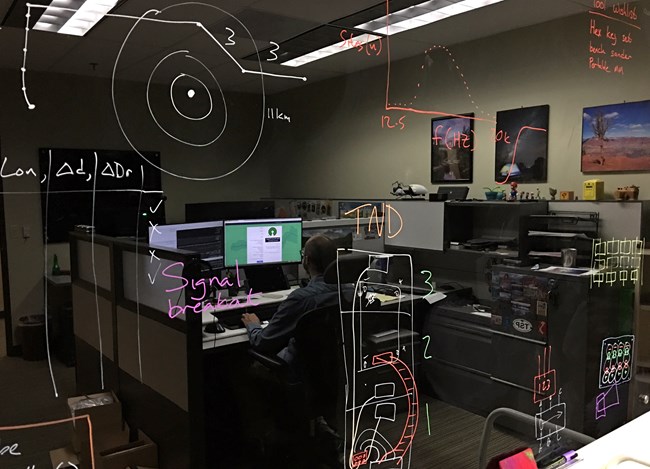

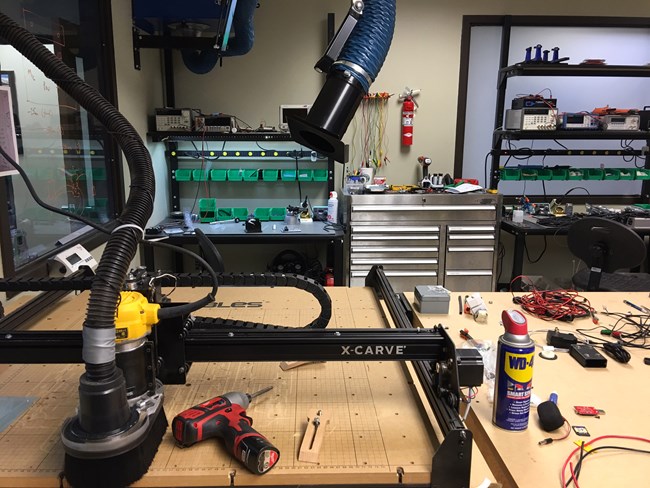

To enter the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division's technical laboratory is to step through the tinkerer's portal to a shop extraordinaire—where assorted circuitry parts, copper wires, nuts and bolts, and power tools lay sprawled across the table in a colorful maze of mysterious purpose. Part tech shop, equipment cage, and staging ground for field trips, the lab is busy with projects in every corner. Specialized tools include a 3D printer, Computer Numerical Control (CNC) Machining, and two electronic rework stations.

Bio-acoustical engineer Christopher Garsha is wearing goggles and soldering electronic components. He is putting the finishing touches on an electronic sound meter sign. When installed in national parks, the sign will display the noise levels of oncoming traffic. The idea is that with instant, visual feedback about their vehicles' output of noise, drivers will slow down. This, in turn, will lower their volume.

With the final part in place, Christopher lifts the 4.5 ft. tall sign to its upright position, walks across the room, and whistles at full volume. Red numbers compliantly flash in response.

"It works!" Christopher beams. Lab mate and physical scientist Damon Joyce nods approval and says that whistling is an easy, low tech way to test the sound responsive equipment.

Julie West / NPS

Damon and Christopher are the idea team for projects involving natural sounds and night skies instrumentation in the parks. With a background in physics, environmental science and data analysis, Damon develops the initial concepts and software needed to run the instruments. Christopher brings chops in computer science and mechanical engineering to transform the raw electronics into final, polished products. Assisting the effort are Colorado State University students Jarrod Zacher and Iman Babazadeh, who help with circuitry diagrams, physical assembly and electrical testing. Together, team members modify and refine each other's developments. The combination of skills makes for robust instruments for use in park units.

The first noise display model was installed at Glacier National Park in 2014. Additional signs were deployed in national park units last year, including Grand Teton NP, Devils Tower NM, Bryce Canyon NP, Lake Mead NRA, and Great Smoky Mountains NP. The goal was to show how loud vehicles were, and introduce park visitors to the concept of decibels in a tangible way based on a familiar noise source: the motor vehicle. Cars, motorcycles and other vehicles produce noise at different speeds, whether from a revving engine or revolving tires. The signs feature a decibel scale with lower and upper limits showing a range of 45 to 85 decibels, with green on the lower scale, yellow in the middle, and red towards the top. Drivers can see the sound impact of their vehicles based on which portion of the scale is lit.

"People in the U.S. know what 68 degrees Fahrenheit feels like, but they might not know what 68 decibels sounds like," Damon says."We want to educate people on what sound is and what sound levels are about, not for purposes of enforcing, but to give people the ability to slow down and make a difference."

Cars are one of many sources of human-caused sounds contributing to noise levels in national parks. Motorcycles, airplanes, human voices, industry, highways, and even park-operated equipment all factor in masking the natural sounds unique to each park. The combined noise levels impact the experiences of wildlife and also park visitors seeking a wilderness connection.

Damon says the signs are one means of raising awareness among park visitors about their impact on the surrounding soundscape. Encouraged by feedback from park visitors and managers alike, he and Chris will be installing more signs in park units across the USA.

Since the first wave of signs was installed, the tech duo has created new signs with improved design and functionality that can be easily reproduced with fewer parts, connections and failure points. The previous signs were cumbersome with multiple components: ten printed circuit boards (PCBs), expensive power relays and separate cables connecting everything. The new signs integrate the boards with compact, energy efficient parts such as solid state power drivers, high-visibility, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and Arduino microcomputers. Joyce says the small devices are far cheaper than the sophisticated sound meters installed in previous versions—a difference of $50 dollars vs. $10,000. They are also low on energy consumption, high on processing power, and can be easily packaged. The signs are also weatherized to better house and protect the sensitive circuitry, which must endure all manner of weather, from harsh sun and battering hail to high winds and freezing temperatures.

"People think of National Park Service staff as outdoorsy, but there are a lot of people in the park who are techie, like me. You can be both at the same time," Damon says. "It's a gratifying process to take inexpensive, hobbyist grade devices and transform them from scratch to work in a way they were not entirely designed to be, in this case, instruments used for scientific data collection."

Another cool natural sounds project in development involves mathematical formulas and 3D printing to design horns as sensitive microphones for amplifying and recording ambient and environmental sounds in the field. On the horizon for night skies, the team is facilitating a range of technical projects, including the use of microcomputers and other cheap gizmos for automating sky quality measurements. Devices of this nature could be useful to parks for monitoring light pollution conditions.

For Emma Brown, an NPS acoustic biologist and policy representative with the division, the instruments that Damon and Christopher build are a practical means of problem-solving and implementing NPS goals in the field.

"By designing and developing new instruments, our engineering team has been invaluable in helping our division measure acoustic conditions in national parks more efficiently and accurately," Emma said. "With this knowledge, park managers can make better decisions about how to minimize noise in national parks. Beyond that though, our engineering team has provided us with tools to reach much wider audiences including other federal agencies, schools and universities, and park visitors, and we have a far better chance of protecting soundscapes for future generations with the help of these communities."

Article by Julie West, communications specialist, Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

Last updated: September 14, 2016