Frank Matero: Thanks Mary. And thanks to NCPTT for the invitation. It's really a pleasure to be here.

So, I'm going to do something different ... what I promised in terms of this submission, but perhaps what you don't associate me often with doing. Which is, I'm not going to talk about materials at least directly.

I want to pick up on something Julie MacGyver said yesterday about the meaning and extend of design. I mean, I literally took the call for papers literally. Seriously. So what I would like to do is just take a few moments to talk about design. And what she alluded to yesterday in terms of the studio was that we have to start thinking about design more broadly as preservationists.

35 years of teaching in 2 design schools, specifically architecture ... I'm more impressed than ever that we need to continue to emphasize that preservation is design, and it's creative. Often in these milieus it's seen as something quite distant and non-creative. And that couldn't be farther from the truth as I'm sure you all know in the audience.

It's such a familiar word, yet it's so loaded with intent and with agency, which is a good thing. It's both a noun and a verb. It's both product and process.

It was the Organic Act of 1916 that established the National Park Service which in turn, designed a national system of, and I quote from the act, scenic landscapes and natural and scientific curiosities for the express purposes of education and enjoyment by the American public. That would later be reinforced, as we heard, by others in 1935 by the Historic Sites Act, which would make the NPS the federal agency responsible for all designated property of national historical and archeological significance - and here's the important part – and interpret that significance through a new master planning process. We heard a little about that yesterday. For site development and here's the other one: An educational program including site museums. So this is really what I want to talk about today.

Because, it was through actually working on a comprehensive project for Tumacácori in terms of the room stabilization that it became very clear that in 1935 it was the intent to emphasize preservation by putting the emphasis elsewhere in terms of interpretation and restoration. It was not on the original fabric. It was on another building that was to be built to complement. So we need to take these things all together. They're not ... We tend to divide them by our disciplinary biases but they really are ... very often they're one concept that was very much inculcated in the park service’s mission and notion by the 30's in terms of the master planning process.

So let me just say a bit about narratives. Because that's really where I want to go with this.The narratives we tell and how we tell them through historical site interpretation and display, help shape our relationship to the past. If preservation is anything, it's interpretation. And it's critical.

Cultural resource specialists, as we all know, must balance between protecting intrinsic tangible values in the material evidence of any historic site, seen here very ironically on the right in this bizarre anastylosis. And the intangible value is related to associated concerns. What I would call the poetics of a site. Nicely represented on the left by Byron contemplating the Colosseum in Rome. It's not about the tangible fabric, it's about all the associations and meanings that have come through time.

The result is often an inherent tension in the push and pull between the emotional and the humanistic on one hand and the rational and the scientific on the other.

Display, a word we don't often hear very much, in the context of preservation, is an interface that mediates and can transform any existing place into heritage. Historic preservation’s approaches and techniques have always been a part of that process. Whether it's as relic as seen here in the Lincoln birthplace, reconstruction in Williamsburg. Williamsburg was, of course, a great contender for the preservation title in the 30's during the Historic Preservation Act.

Post-modern translation is in the famous Franklin Court Ghost House of 1976. Then what I would call a mash-up in contemporary language, this one from Rome in the Palazzo Altemps Square. The author, the architect as author has selectively chosen bits and pieces in a brick lodge sort of situation. Very consciously. This is not what Tumacácori is, as you will see, which is why I use the term historical pastiche.

These different approaches often result in different meanings so that visual legibility affects the way information is preserved and transmitted and therefore how we experience a site.

Three basic questions that concern all involved in the preservation of cultural resources therefore are:

How should we experience historical sites? Especially those that are fragmented and illegible?

2. How does conservation shape what we see, know and feel?

3. How could display promote an effective and active dialog between the past and the present?

Well, one interpretive practice, bit of a bogey man, has been reconstruction, which has loomed large in the history of American preservation and especially in its federal expression through the National Park Service. Often revealing an agency in conflict over elitist professional concerns about authenticity and historical interpretation against public expectations and the desire to be entertained.

Against the backdrop of well known debacles such as the reconstructive replica of Washington's birthplace in 1932, albeit inherited by the park service, but we heard about this yesterday. The service steadily moved towards policies favoring preservation over restoration as a general rule. Although later exceptions such as Bent's Old Fort, were reconstructed in response to local interests and Congressional influence. We all know what that can do.

What is less well documented, and therefore less well known, are early NPS efforts to develop an appropriate response for both prehistoric and historic ruin sites, in terms of balancing their preservation, interpretation and display. And such, is Tumacácori. On the right Bent's Old fort, on the left Washington's birthplace. Tumacácori there, chronologically, in the middle.

I believe Jake's probably going to talk about this more through adobe sites. But many of know that the formation of federal preservation ethos in the United States began early in the late 1870's and 80's with public interest in the protection of prehistoric sites in the West, culminating in the Antiquities Act of 1906.

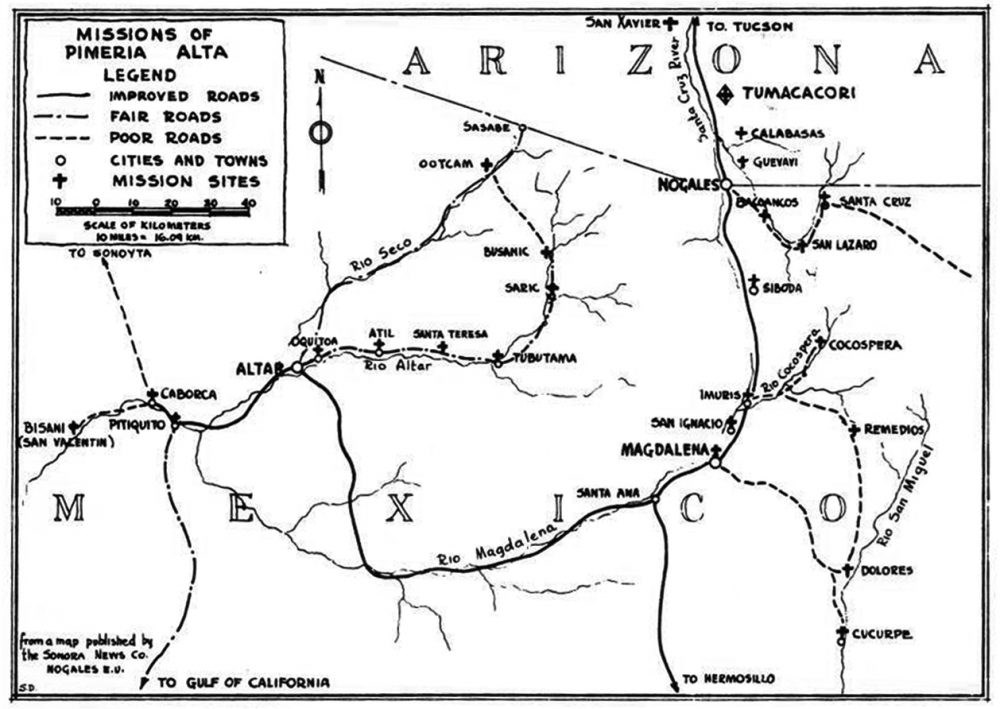

Mission San Jose de Tumacácori was not only the first historical site, meaning non prehistoric post-contact site to join the 18 newly created National Monuments Program in 1908, it was among the first Spanish colonial sites to be designated by 1916. In fact, it was the first, along with two others.

In the United States, recognition and celebration of regional identities began after the Civil War, coalescing in the first national expressions of the Philadelphia centennial of 1876. States and regions were presented through their distinct pasts and the American West was displayed for the first time emphasizing, and I quote, its Aboriginal antiquities and quaint Spanish colonial traditions. This was especially true for the exhibits of California, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas.

But probably the first serious and sustained effort to study and preserve the country's Spanish mission architecture began in California, with the founding of the Landmarks Club in 1895, under the leadership of its charismatic founder, Charles Lummis. And with early preservation projects you see here, such as San Juan Capistrano.

Efforts followed elsewhere in San Antonio, Texas, Santa Fe, New Mexico, right here. And Tuscan, Arizona. Each claiming a unique variant of the country's Spanish legacy.

In 1921, architect and archeologist Prentice Duell, published his three part study of the Arizona Sonoran missions in the Architect and Engineer. Thus bringing the less known Kino missions to a wider, albeit, professional audience. Soon thereafter, in 1928, University of Arizona professor Frank Lockwood, Kino biographer and Arizona booster, advocated for the touristic development of the Arizona and Sonora mission chain, declaring that the Kino Missions were far more interesting historically and far more beautiful architecturally than the California chain.

It is within the larger context of interest in the Spanish colonial and its inclusion in the national story through the National Monuments Program in 1906 and later the National Park Service in 1916.

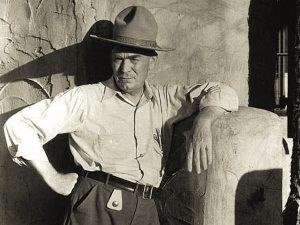

I now want to turn to the early preservation and interpretation of Tumacácori Mission and its museum and later visitor center.That story certainly could not be told without Boss Pinkley. Frank Boss Pinkley began his National Park Service career on December 12, 1901 as resident custodian of Casa Grande Ruins. A career that would span almost 40 years.

Pinkley believed in the intrinsic importance of national monuments in portraying the American story. Despite their often lesser position compared to the larger, more scenic and popular national parks. And this often placed him at great dispute with the chiefs of the park service.

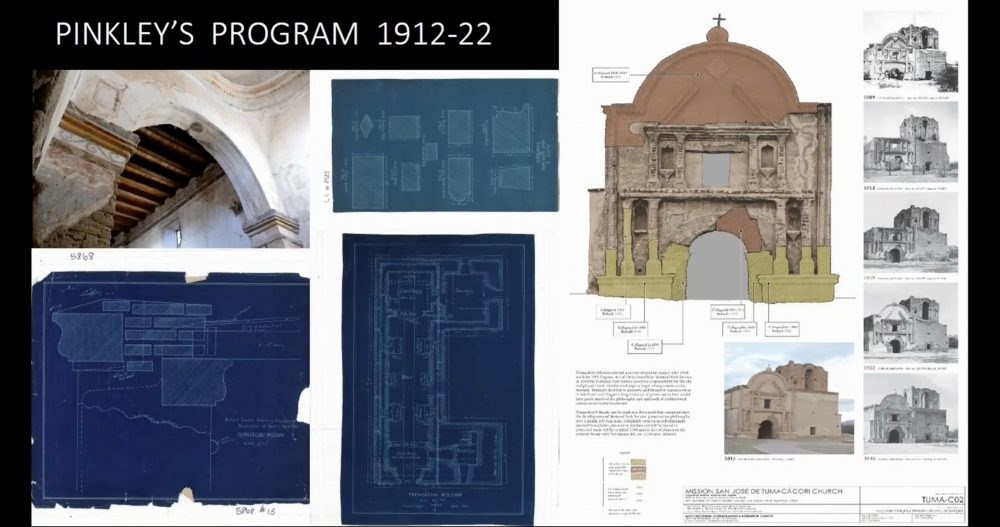

On June 19, 1918, six years after an initial visit to Tumacácori, the young Pinkley was sent from Casa Grande to the mission site to develop plans for its preservation and visitation. 1918, this was quite early. On March 1919, he began major work to stabilize the church. Work focused, as you see on the right, on the repair of the belfry and the second story of the bell tower, as well as the underpinning of the east sacristy wall and the whole east side of the church proper. On the principal façade, the broken arch entrance was restored in kind with intentionally exposed adobe to show the construction and new wooden doors were installed.

In order to fully understand the site, Pinkley believed it was necessary to study other missions in Mexico as well as California, and so, in 1920, he made several exploratory trips. The first to Sonora, where he recorded the Kino mission churches. You see a drawing on the left there. Then on to the California missions, where he saw many under restoration.

Sorry, the left image is early 1912 blueprint or drawing of Tumacácori.

He was interested in building technology. Pinkley noted a number of issues that still plague heritage professionals today. On the question of architectural authenticity or structural integrity, he wrote, and I quote him again, "Here is one of the problems of restoration. To restore exactly as the original was built and then put in extra bracing, or to change original design enough to give it the necessary strength."

And on the subject of whether to preserve or to restore, clearly a major issue at Tumacácori and for the National Park Service during this time period, Pinkley noted, and I quote, "The cheerful way in which some of these landmarks of other times have been spoiled makes one pause over just how much restoration should be done. Protection against time and the elements we all grant must be given. Although it sometimes takes away the beauty of the ruin."

Upon his return and with new funds in hand, Pinkley set to reinstate Tumacácori's missing roof. Thus stabilizing the knave walls and protecting the precious painted interior plaster. This was really done almost as an in-kind shelter and also structurally to laterally brace the walls.

Based on his Sonoran and Californian experiences, he designed a replacement roof. Part traditional, part modern as you can see in the left hand ... lower left hand, detail. He replaced and repaired the drainage canales as well. In addition he reconstructed the collapsed façade pediment based on an 1889 photograph which you can see on the right hand. This is our photomontage and drawing of all the campaigns of change to structure over time.

Later work moved site interpretation closer to the restoration as additional façade elements were restored for fear of destabilization. In other words, after 1940, park service started to drift away from this notion of stabilized ruin and moved more to completing the picture. Something that was definitely not in the agenda earlier.

By 1933, the approximately 80 historical and archeological areas that had been acquired and developed under 3 separate federal departments and bureaus, all came under the stewardship of the National Park Service.

We heard this yesterday.

In order to guide this new responsibility, the Historic Sites Act of 1935 was passed. Making the service the federal agency now solely responsible for the protection and management of all federally recognized historic sites and placed the responsibility of defining historic preservation for the entire country.

The diverse array of sites opened up the debate for the most appropriate approach to take in their interpretation and display. Wishing to avoid further debacles of reconstruction, such as Washington's birthplace, the service vowed to stress preservation over restoration with Jamestown as the federal response to Williamsburg.

Stating, quote,

"The historic structures to be placed on display when preservation techniques are perfected, are expected to be unalloyed, authentic originals."

Use that next time in a meeting with a superintendent, that'll be really effective.

With these new responsibilities in place and the funding available through New Deal Public Works projects, the service was poised to expand its mission to include education. Also part of the 35 Act. While natural parks were first appreciated for their scenic values, later, it was their importance as wildlife refuge and ecological preserves, as was argued by natural scientists. Which demanded greater understanding and management after 1916. Hence the first museums are natural museums. Because of the shift in the value of these natural resources. Most historical and archeological sites lack the high scenic, and hence recreational value, so interpretation was critical to best introduce the public to the importance of these sites.

By 1918, trail museums became official policy and in 1922, the first official museum opened in Yosemite National Park. Dedicated to natural history and its knowledge. I think Ethan mentioned this yesterday.

This was followed by Maier’s now famous rustic designs. The one I show you here is for Fishing Bridge Museum. Which is a real tour de force of rustic contextualism.

But, at the same time in 1921, planning began for a new museum at Mesa Verde, dedicated to the parks prehistory. With Jesse Nusbaums elegant design, derived from Zuni and Hopi buildings, which were displayed in the Bureau of American Ethnography's books.

In 1929, Harold Bryant was appointed head of the new Division of Education and with New Deal funding, he constructed museums and new museum exhibits with the Division of Education, had a wide and powerful reach. So it’s against this background that the Tumacácori Mission and study trip developed.

Now, let's turn to the Tumacácori Museum. From the start, the service employed historians and archeologists as well as architects, landscape architects and engineers to insist in the interpretation and development of the parks. By the early 1930's, late 20's actually, the service institutionalized its approach through guiding principles embodied in the park master plans. Which combined historical research, archeology, infrastructure and architecture to direct all future work.

Until the advent of Mission 66 and its embrace of modernist principles of design, all site museums loosely followed some form of regional contextualism. Defined as fitting into the natural or cultural setting of a place. Often context was equated with rustic design employing local materials and or vernacular uses of those materials. However, occasionally, more ambitious efforts were employed to design a facility to educate the public by displaying the very cultural traditions of the monument it served.

This was by no means relegated to park museums only, as seen in the countless examples across the country, and here in the Southwest the Spanish pueblo revival. So here's a really good example close by of a literal copy of an existing church at Acoma, to the Museum of Fine Arts.

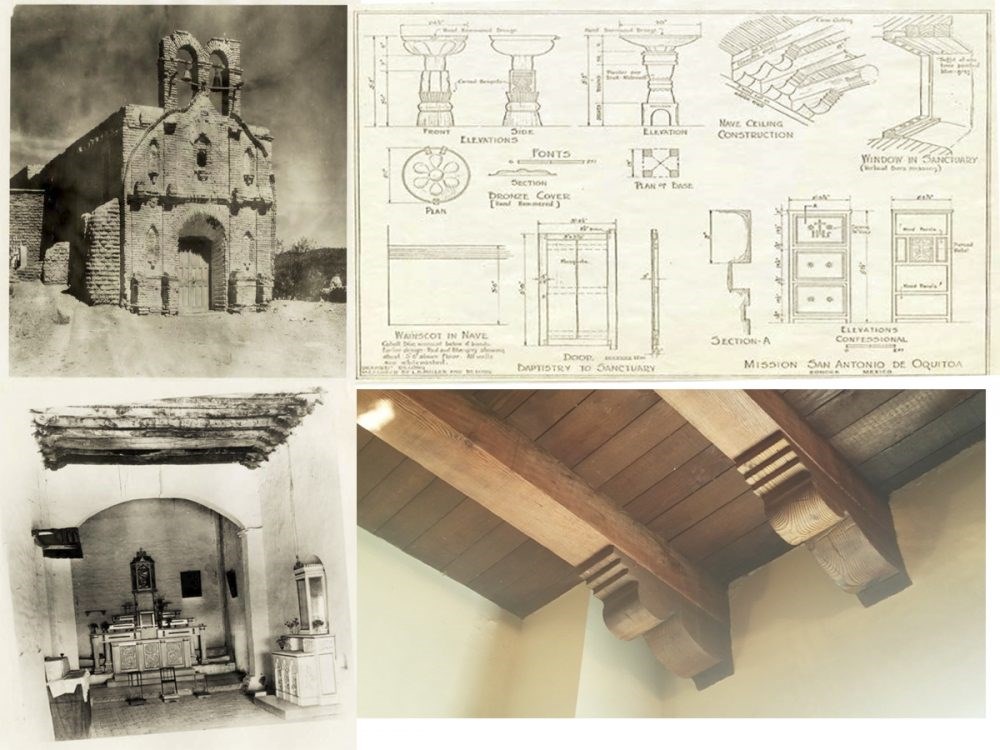

Tumacácori's museum was different. Whereas reconstruction had been advocated for public buildings at San Jose missions, seen here on the left in San Antonio, Pinkley and his team had a different and specific idea about a museum from the start, seen here on the left. In '36 he wanted a building that would complement the mission’s architecture. Low and subordinate to the ruins. Be situated close to the parking lot, the latter increasingly critical for the new order bound visitor.

The façade was to be simple, the plan to accommodate easy circulation. And 2 of his most important requests were to incorporate accurate architectural elements copied from other Sonoran missions as exhibits to display Spanish colonial architecture of the region. And then to design an open viewing room with scenographic effects so visitors could gaze upon the church in advance of their site visit while still in the museum.

And I'm just going to quickly go through and add some details. Always on the left are the Sonoran mission photos and drawings from the expedition notebook and on the right, Tumacácori's Museum.

So the piers and arcada, the museum portales were copied from Caborca while painted the dado, lobby ceiling windows, rejas canales, they were all based on a combination of mission building since they were very common elements. The great shell motif of the main entrance of the Tumacácori mission was copied from the entrance at Cocóspera, while the wooden doors were based on those at San Ignacio.

The entrance lobby ... the view room framing the church itself, a largely decorated, painted groin vault seen on the right, celebrated the forms as found in San Ignacio, and Xavier, and Tubutama. The entrance lobby ceiling was carved with corbels and vigas similar to those at Oquitoa. These are all Sonoran missions.

The high walls of the compound contained and defined the frontage of the property without blocking the view of the church. You can see it on the left here on the left image and the mountains beyond. They also kept the parking lot from intruding into vista once in the park. The main arch entrance within the blank walls reinforced the fortified design of mission complex. But never literally.

The opening of the complete museum in 1940 with scenographic views, exhibits, dioramas, patio garden and comfort station - yes indeed it had one of the earliest designed comfort stations - signaled the beginning of a new era for site interpretation of a national park. It also marked the end of Pinkley's long effort to promote display and education at national monuments. For on February 14, 1940, the boss died.

Pinkley was the chief author of Tumacácori's early preservation plan and its unusual museum culminated his efforts in appreciation of site values through innovative interpretation and display. What is clear is that his insights were almost always correct and his ability to realize them highly effective. No small achievement in an agency that was still experimental in development and largely under-funded.

Today Tumacácori remains a case study of complementary methods of site design, room stabilization and interpretation. With the National Park Service realized its evolving commitment to education and I end by quoting, from 1935,

"Contact with real things, with unusual things, awakens a desire for explanation for an increase of knowledge."

Thank you.

Last updated: April 7, 2025