Last updated: December 23, 2023

Article

HBCU Grant Recipients in the National Register of Historic Places

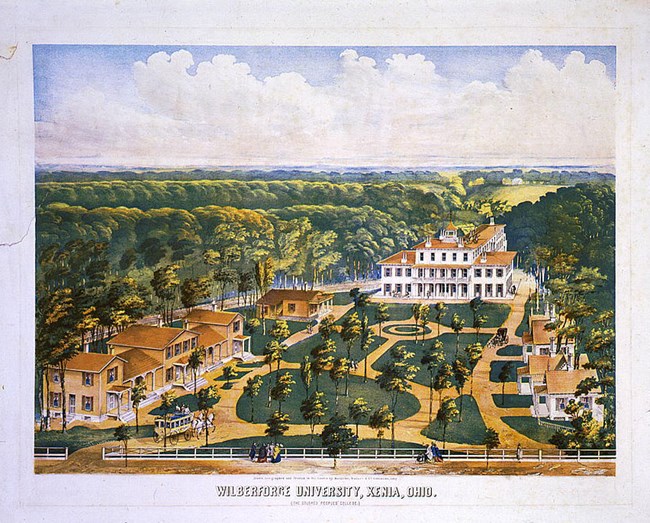

Lithograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

Facing enslavement, poverty, and discrimination, higher education was almost entirely unavailable for Black Americans in the early 19th century. As abolitionist sentiment began to build in the lead-up to the Civil War, many Black and white Americans alike believed that education was necessary to prepare the formerly enslaved for citizenship. The first HBCU was established in 1837 as the Institute for Colored Youth (later Cheyney University) in Cheyney, Pennsylvania, by a Quaker philanthropist. While a few more schools for Black students were established before the end of the Civil War, often by white Northern evangelicals, the majority of HBCUs were founded by both Black and white educators during the Reconstruction era.

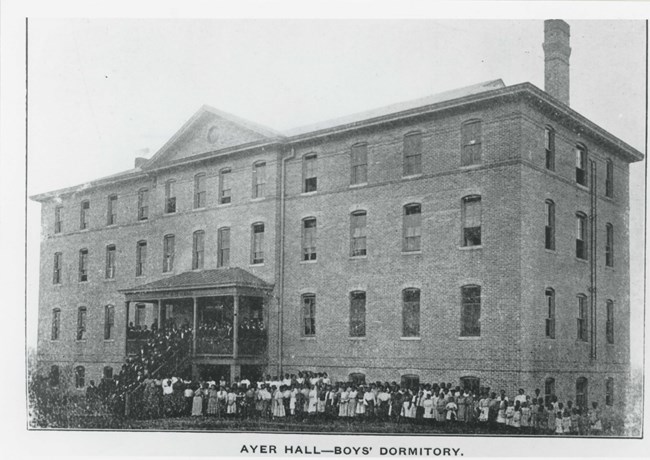

Photograph courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Despite additional support from the federal government and increasing state involvement in the schools, HBCUs frequently struggled with funding and facilities. In some cases, the schools relied on the manual labor of their students to build campus facilities, which were often constructed of cheaper, flimsier materials like wood. These buildings were at higher risk of destruction during natural disasters or fires, and many were lost to history. The remaining historic buildings on these campuses are often sources of great pride, and serve as reminders of the immense barriers that these institutions have faced to fulfill their missions.

Because of their historical significance, many of these campus buildings have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The properties featured below reflect the rich, varied history of these insitutions, and have each received rehabilitation grants through the National Park Service's HBCU Grants program. Through this grant program, any accredited HBCU is able to apply for funding to support preservation projects for properties listed in or eligible for the National Register, including architectural plans, historic structure reports, and the physical rehabilitation of historic buildings. Since the 1990s, the National Park Service has awarded nearly $100 million in grants to help preserve the places, resources, and stories of HBCUs.

Grant Project Highlight: Lyttle Hall

Additional Resources

Historically Black Colleges & Universities Grant Projects (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)HBCU Application Resources - Historic Preservation Fund (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

What is an HBCU? | White House Initiative on Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence, and Economic Opportunity through Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

Bibliography

Green, Hilary and Keith Hébert. "Historic Resource Study of African American Schools in the South, 1865-1900." National Park Service, 2022. DataStore - Historic Resource Study of African American Schools in the South, 1865–1900 (nps.gov)Koch, James V., and Omari H. Swinton. Vital and Valuable: The Relevance of HBCUs to American Life and Education. Columbia University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.7312/koch20898.

National Center for Education Statistics. "Fast Facts: Historically Black Colleges and Universities." Institute of Education Sciences, 2023. Fast Facts: Historically Black Colleges and Universities (667) (ed.gov).

Sanders, Crystal R. "Wilberforce University: a pioneering institution in African American education." OUPblog, February 25, 2015. Wilberforce University: a pioneering institution in African American education | OUPblog.

Thurgood Marshall College Fund. "History of HBCUs." TMCF, 2019. History of HBCUs | Thurgood Marshall College Fund (tmcf.org)

Veney, Cassandra R. “The Ties That Bind: The Historic African Diaspora and Africa.” African Issues 30, no. 1 (2002): 3–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167082.

The content for this article was researched and written by Emma Trone, an intern with the National Register of Historic Places.