NPS Photo Dallas, Lowndes, and Montgomery Counties in the Early 1900sIn the years of post-reconstruction Jim Crow laws, suppression of African American citizens' right to vote through the use of targeted voter registration restrictions and intimidation was widespread in the American South. Because of this, 0% of the African American population in Lowndes County was able to vote, and only 2% percent in Dallas County. The Murder of Jimmie Lee JacksonOn the evening of February 18th, 1965, a night protest took place to free Southern Christian Leadership Conference supporter, Rev. James Orange, from the Perry County Jail, in Marion, AL. Alabama state troopers violently broke up the demonstration, resulting in the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a civil rights activist and Perry County native. Jackson was shot in the abdomen while protecting his mother and grandfather, he died from his wounds on February 26th, 1965. In response to Jackson's death, a march to the Alabama Capitol in Montgomery was planned — Sunday, March 7th, was the chosen day for the first march attempt. First March AttemptOn March 7th, approximately 600 non-violent protestors, the vast majority being African-American, departed from Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma intent on marching 54 miles to Montgomery, as a memorial to Jimmie Lee Jackson and to protest for voter's rights. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were met by state troopers and local volunteer officers of the sheriff's department who blocked their path. Second March AttemptIn response to the attack, Dr. King called for another march on Tuesday, March 9th. Known as the Ministers March, Dr. King led a second march of approximately 2,000 protestors to the site of the Bloody Sunday attack where state troopers blocked the path of the march again. Dr. King and other clergy led the group in prayer, turned them around, and led them back to Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church. Because of this, March 9th is also known as "Turnaround Tuesday".

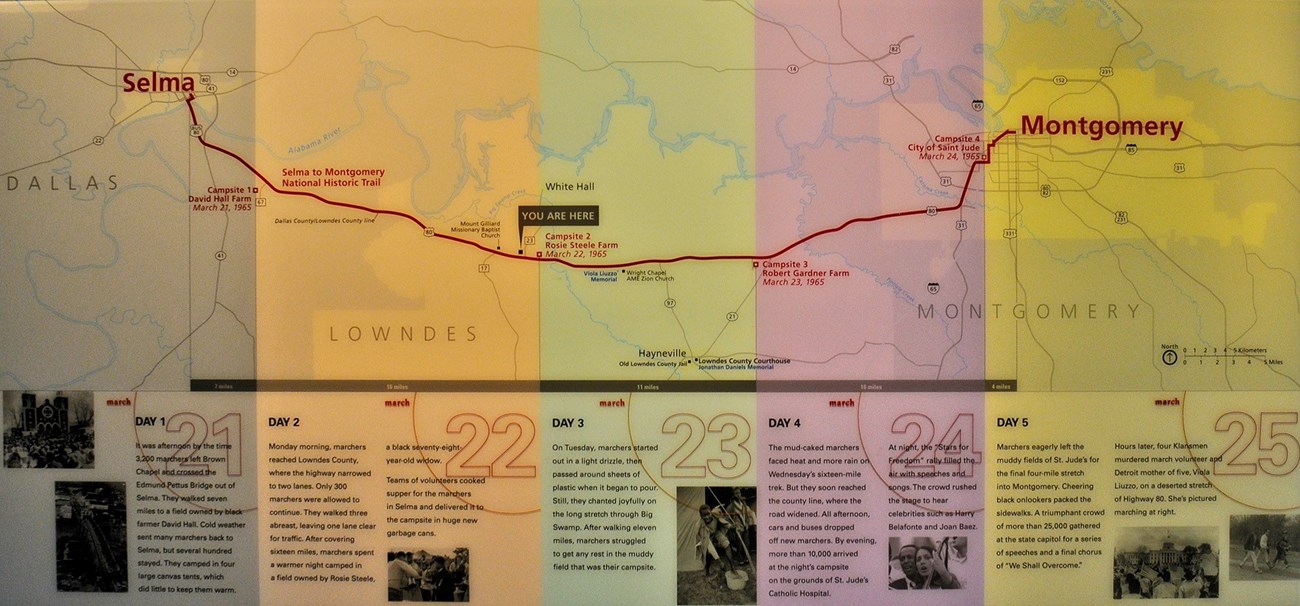

Photo courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History Third and Final March AttemptOn March 17th, Federal Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. ruled that the march could go on to Montgomery and provided federal and state protection for the marchers. Alabama State Troopers and Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies were ordered not to impede the marchers in any way. On March 21st, the final Selma to Montgomery March began, with more than 8,000 protestors departing from the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church to begin the five-day march. Marchers spent nights at four campsites along the trail — the final campsite at the City of St. Jude, on the outskirts of Montgomery, had thousands more protestors waiting to join the marchers on the last leg of their journey. Passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965The march brought national attention to the voting rights struggle faced by African Americans, and the media coverage of the march and the violent protests leading up to it put pressure on Congress and the Johnson administration to take action on the issue. On August 6th, five months after the marches, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law, making it possible for African Americans in the South to register to vote. After the passage of the Voting Rights Act, registration of African American voters in Central Alabama increased dramatically. |

Last updated: October 24, 2023