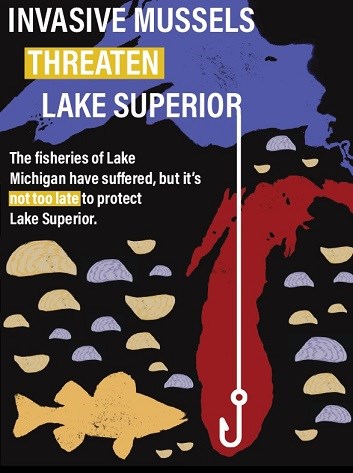

graphic by Leah Carter

The Story of the Yellow Perch

Before the mussel invasion in Lake Michigan, Yellow Perch were an abundant, culturally important fish that supported profitable commercial and recreational fisheries. Yellow Perch was so famously abundant that in lakeside cities such as Milwaukee, WI, office workers could often be found catching perch during their lunch breaks.

However, this abundance didn’t last forever. Beginning in 1996, commercial fishing in Wisconsin Lake Michigan waters was closed and the sport bag limit, a limit on how many fish an individual can catch per day in order to maintain the population, was cut. Historically, it was around fifty, but today, it’s only five. In 1992, Wisconsin sport anglers recorded harvesting 886,496 perch in Lake Michigan waters, according to DNR records. By 2016, the count had dwindled to just 2,132.

What Happened to the Fisheries?

Ben Turschak, a fisheries research biologist working with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, is concerned, along with many other people, about the changes that the Great Lakes have gone through since the introduction of invasive mussel species. Turschak shared much of the information in this article with the article’s author, Leah Carter.

The invasion of the zebra and quagga mussels, which are native to Eurasia and were carried to the Great Lakes by international boat traffic, have led to major changes in the health of the Great Lakes and the population of their fish species. While both quagga and zebra mussels cause significant problems, quagga mussels (which proliferated throughout most of the Great Lakes in the early 2000s) are prolific breeders and far outnumber zebra mussels. A female quagga mussel is capable of producing up to one million eggs per year.

Historically, Lake Michigan supported an abundant variety of plankton, an important keystone food source which supports the entire food web. Despite their tiny size (they are only about as large as a fingernail), a single quagga mussel is capable of filtering up to a liter of water per day. This means they can consume plankton at a very rapid rate. Since the widespread mussel colonization of the early and mid 2000s, plankton levels in the Great Lakes have declined, including the loss of the spring phytoplankton bloom. When mussels filter plankton from the water, it becomes clearer, enabling sunlight to penetrate deeper and allowing more algae to grow than under normal circumstances. While we have lost much of the phytoplankton from the water column, algae growing on the lake bottom have flourished since the mussel invasion. It is common for large amounts of this algae to become detached and wash ashore, littering our otherwise pristine beaches. If you have seen this nuisance algae, it is likely that invasive mussels are to blame.

In the early 2000s, many sportfish populations were healthy and increasing. Unfortunately, since their arrival, the invasive mussels have consumed so much of the plankton and nutrients that the food web relies on that important prey fish populations have struggled to maintain high numbers. This has lead to the decline of predator populations such as whitefish, yellow perch, and salmon. Today, it is estimated that for every pound of prey fish swimming in Lake Michigan, an estimated three to four pounds of quaggas live on the lake bed. In some lakes, including Lake Michigan and Lake Ontario, management agencies have had to reduce the number of salmon and other predator species they stock in order to avoid a collapse of the food web and to maintain popular and valuable recreational fisheries. In Lake Huron, that food web has already collapsed. Not only have the population numbers of these fish declined, but the health of the fish is in trouble too. A higher energy density being found in fish means a fatter, healthier fish. However, the energy density of whitefish tissue has been found to have decreased significantly since the mussel colonization. This is possibly due to a population decrease in the invertebrate prey upon which the whitefish rely.

In the face of invasion, not all species have suffered. Some have managed to adapt to their changed food web. Round gobies, an invasive fish species, are well adapted to feed on the pesky mollusks. After the mussel invasion, the gobies flourished thanks to their nearly unlimited food supply. In turn, fish that prey upon the round gobies such as walleye and lake trout are thriving. But despite these positives, the overall fishing industry of Lake Michigan has severely declined.

Invader Warning

It was previously thought that Lake Superior’s waters, which are frigid and low in the calcium mussels need for shell development, were inhospitable to quagga and zebra mussels. Recent investigations have found that these invaders have indeed found their way into Lake Superior. As recently as 2020, invasive mussel colonies have been detected (and manually removed) in Lake Superior waters at multiple National Park locations, including Apostle Islands National Lakeshore and Isle Royale National Park. Fortunately, the lake boasts relatively few numbers of invasive mussels compared to Lake Michigan.

It is more important than ever to take action to prevent the spread of these tiny invaders now, while those numbers in Lake Superior are still low. If the spread is not stopped, this Great Lake could find itself having the same fate as Lake Michigan, with its reduced biodiversity and struggling fishing industry. Since the fingernail sized mollusks easily attach themselves to hard surfaces, and they can survive for up to 5 days without water, it’s easy for them to be spread by human activities. Scientists and resource managers believe the number one vector for the spread of invasive mussels is by hitching a ride on boats, paddles, and other recreational equipment.

What Can You Do?

Boat owners, fisherman, and other water-based recreationists can help curb the spread of invasive mussels and other aquatic invasive species by following a few simple rules:

1. Make sure to drain all bilge water at least 100 ft away from bodies of water.

2. Thoroughly wash all boats, paddles, kayaks, canoes, jet skis, and any other equipment with high pressure hot water (140 °) when moving between bodies of water or let your equipment dry for at least 5 days before moving to a new water body.

3. Don’t wash or dump bait, mud, plants, or bilge water into another body of water.

4. Learn to identify invasive mussels, and educate others.

Keep an eye out for the new boat cleaning stations coming to areas in or near our Lake Superior national parks. Together, we can all protect the biodiversity, beauty, and industry of Lake Superior.

Last updated: May 19, 2021