Season 1

2. Stewardship Savvy 02: Bob Cook

Transcript

TBD

This second episode of Stewardship Savvy takes us on a wade through the salt ponds of Cape Cod National Seashore with herpetologist Bob Cook.

Podcast

Stewardship Savvy gathers voices and stories from people within our parks. Created and hosted by the Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network, a part of the Inventory and Monitoring Division, join us as we hear from GIS specialists and park scientists about why they do what they do at the National Park Service.

TBD

This second episode of Stewardship Savvy takes us on a wade through the salt ponds of Cape Cod National Seashore with herpetologist Bob Cook.

Mark Adams: It's great, right?

Narrator: Yeah.

Mark: It tells a story, if you know how to read it.

Narrator: This is a story about the memories encapsulated in the natural landscape and the generations of people who’ve stood on the shore and tracked the ceaselessly encroaching sea. This is also Stewardship Savvy, a show from the National Park Service highlighting the individuals who use their unique skills and perspectives to make the park service’s mission possible: to preserve America’s cultural and natural resources. I’m Colleen Keenan. In this first episode, we’re talking with Mark Adams, a GIS specialist for Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts. To begin, Mark shares with us about how he uses mapping software to visualize and describe the natural landscape for scientists and park managers alike. We met in the town of Truro on Cape Cod, which was once known as Tashmuit, homeland of the native Wampanoag people who originally settled there. The national park operates out of the Highlands Center. It’s a complex of buildings and old roads that was once an air force base. Plants poke up through the cracks in the pavement and some of the abandoned buildings sport broken windows and salt-sprayed exteriors. Nature infiltrates this space as the workers inside look outward to answer questions about our unavoidable entanglements. Mark has been working here for most of the past 30 years.

Mark: I came to the park in 1991 to be a research assistant for a part-time project. And that was the dawn of GIS in the park service.

Narrator: If you didn’t know, GIS stands for “geographic information system.” Basically, GIS software allows the user to find patterns in all sorts of spatial data. For Mark, GIS is a tool to generate accurate 3D models of Cape Cod’s landscape and then to visualize its changes over time. In the part-time project he was working on, he became really familiar with Cape Cod by comparing historical photos, documents, and surveys to modern ones. These comparisons painted a picture of how the peninsula has transformed over the past few hundred years.

Mark: So, I had this great opportunity to visit archives, and then roam around in the woods and find locations shown in old photographs and see what the story was about how they changed.

Narrator: Mark has continued to reveal stories of change through his work with GIS. This technology allows him to take historical and modern landscape data sources and put them together accurately in the same reference frame. As a result, Mark and the scientists he collaborates with can make measurable observations about processes of change in the real world.

Mark: Well, fortunately as a GIS person, in a sense I'm a technician, not a scientist. You could debate that, but there are experts in every scientific discipline. And my job is to integrate all that scientific information, and maybe do some analysis on it, and visualize the scientific information in a way that applies to the concerns of the moment.

Narrator: Although its basic function has remained the same, GIS technology has evolved dramatically since when Mark started working for the park service in the nineties.

Mark: Back then, GIS was a very hefty affair running off workstation computers that cost $25,000 and required really elaborate logins and scripting language.

Narrator: Over the years, he’s converted analog materials, like paper maps and photos, into digital versions for use within the GIS environment.

Mark: GIS started out to be just trying to create digital copies of these analog maps that people have made through photogrammetry.

Narrator: What's that?

Mark: Well, photogrammetry is basically turning photographs into maps.

Narrator: Now there are less intermediate steps but GIS is still reliant on information from the physical world to make a digital representation of it. Satellites and advanced equipment for measuring geographical features have made it much easier to collect accurate geographical data. And modern computers and GIS software are way more efficient than those chunky $25,000 ones. But, according to Mark, that doesn’t mean that paper maps and field surveys are obsolete.

Mark: You know, we're in this digital age, but paper's still useful.

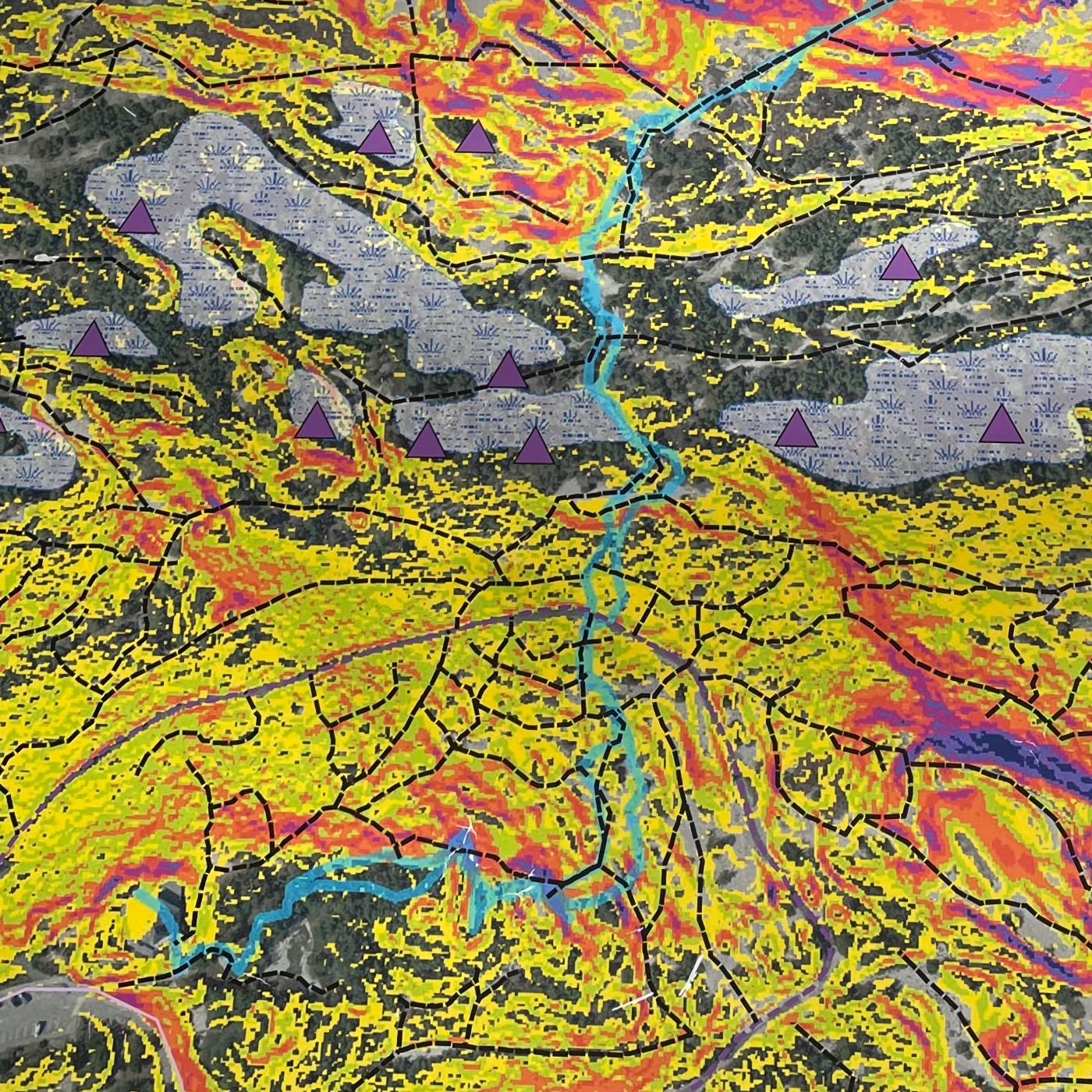

Narrator: When I walked into his office, I saw Mark’s multi-monitor computer workstation, nuzzled among rolls of historical and computer-generated maps. Vibrant multi-colored maps of Cape Cod are taped on the wall behind him like an unconventional stained glass window, one depicting the local geology of where we sit. Mark gestured at one of these maps and explained how these compelling visuals are more than just pretty pictures.

Mark: This is from the early coastal survey maps and let's see. Yeah, this is actually regenerating forest and pasture land, and all of this was deforested. And then— but the colors now show the current forest. So this pea-soup green is the pine oak forest that we have today. And this kind of blue-green is the mostly oak forest.

Narrator: It's pretty beautiful.

Mark: It's great, right?

Narrator: Yeah.

Mark: It tells a story. If you know how to read it.

Narrator: Equipped with an excess of information and data, Mark is tasked with the job of synthesizing and simplifying.

Mark: And I have this whole just mountain of paper maps that have been printed over the years. And I don't throw them away, because someone will walk in and say, “Hey kid, do you have a map of the forest? Can you make me a map of the forest?” And then I’ll be like, “Well, yeah, I've done that about ten times in the last 30 years.” So here's just a map that’s laying around that shows, you know, this is the extent of forest in 1848.

Narrator: By layering different data sets on a 3D map in GIS, it’s possible to identify patterns and give multi-dimensional answers to questions about our physical world.

Mark: So what GIS does, is it enables you to put those locations into the real world precisely. But the real power of GIS, then, is that you can overlay other data with it.

Narrator: GIS can put information like forest density from 1848 on the same page as current measurements. It allows us to extend the timeline of our knowledge farther back into history and to make more accurate predictions.

Mark: So, you can make these really eye-popping comparisons. None of this is meaningful unless we can put everything into the same reference frame.

Narrator: Each map produced depends very much on the question it’s designed to answer. The Cape Cod seashore is characterized by rapid coastal change, so Mark’s work offers useful perspective to the past and future of the landscape. For example, in 2007, a new inlet was forming around Chatham in Cape Cod. Personal property as well as park land was threatened, and locals called for the new waterway to be artificially filled with sand. So, how can we know what the right thing to do is? Well, analysis with GIS can help suggest a course of action by revealing the longer-term geologic patterns of this dynamic barrier island system. A GIS technician interprets and communicates these lessons in a map.

Mark: It's a skill to take information and turn it into a map. And another thing that people don't understand enough is that there should be an idea behind each map.

Narrator: It takes scientific judgment to eliminate distractions and focus on the necessary information to craft an effective map. To respond to the inlet formation question, Mark told me, GIS analysis would reveal that this coastal area was previously an inlet over 150 years ago. Because of the dynamic nature of this barrier island system, it would likely return to that state again even if people tried to build on it or artificially fill it in. Understanding these natural cycles of change is critical in advising science and land management decisions. It helps park managers make informed decisions that will protect our people and places.

Mark: And it's like mining for gold, you know. You don’t want to know where all the other stuff is. You just want to know where the gold is.

Narrator: For practical questions like the possibility of erosion and sea level rise on the coast, GIS analysis could be the difference between a water view property and a waterlogged one. Mark uses GIS to strip away extraneous information, find the gold, and contextualize it in the proper frame of reference. To answer real-world questions, Mark sometimes needs to focus on minute details and sometimes needs to see the big picture.

Mark: You're constantly alternating back and forth between drilling down to detail and zooming out to kind of a global scale. That's another really powerful thing is to be able to zoom seamlessly from a bird's eye view down to a point location.

Narrator: Some environmental changes on Cape Cod can be observed on that small scale, year to year, like the erosion of its coasts. Sand moves northward along the coast of Cape Cod, pushed by the forces of waves and wind. The deposition of this sediment reshapes the coastline and forms beaches. Mark told me, if you were sitting at the beach, the flux is equivalent to a dump truck of sand passing by every ten minutes. And at the seaside cliffs at Truro, the coastline retreats about three feet every year. Mark and I walked on a dirt path overlooking the shore to see this transformation in action.

Mark: And you know, a lot of that information is surveyed based on these ancient techniques of optical surveying. Basically stakes in the ground and observations and, you know. The Egyptians did it to do the pyramids and—we almost never overlaid all these timescales together. So, you know, monitoring timescale is like, you know, twenty, forty years. If we're good. And then historical timescale is like, okay, 400 years. And then native timescale lays on top of that. Let's just take—I mean, basically, yeah, the glaciers retreated, first evidence of humans here. It's like 11 to 12,000 years ago. Marindin was here in 1890. Graham Giese came here in 1955 and he did surveys through the eighties. And then I started working with him in 2005. And I don't know. Who's next?

Narrator: So, it’s all a part of this longer story. Some changes must be observed over longer time scales—over decades, centuries, or millennia. For example, Cape Cod’s characteristic shape, like that of a flexed arm, was carved over the past 5,000 years by the constant battering of wind and water. Mark works in the footsteps of generations of coastal observers. As we walked, he spoke fondly of a surveyor who laid the groundwork for our current understanding of coastline change in Cape Cod. Henry Marindin spent the years of 1887 to ‘89 traversing the long eastern coast of Cape Cod, now the Cape Cod National Seashore. He recorded accurate topographic profiles and erosion rates of the beach for use in future comparisons.

Mark: You know with Marindin, he didn't know a lot of what we know now about how the ocean works and the trends and sea level and stuff. But he knew that if he had good measurements, that somebody else could measure them again and use it. It was really—it gives you a lot of faith in that culture of science.

Narrator: Marindin’s painstaking work, performed without modern equipment and technology, continues to provide critical insights into the rates and processes of change on Cape Cod’s shoreline. We inhabit a world of constant flux, and historical fingerprints provide the clues to decoding the nature of these changes. The Cape Cod of several thousand years ago would have been entirely unrecognizable to us now.

Mark: You know, Georges Bank was an island. Nantucket and the Vineyard were bumps on a vast coastal plain—

Narrator: Oh! Just then, a snake surprised me and interrupted Mark’s meditation on millennia of geologic change. It stopped us short and crossed the dirt path that we were walking on.

Mark: Oh, hi!

Narrator: Wow.

Mark: Beautiful milk snake.

Narrator: Wow. I don't know that I've seen that type of snake.

Mark: Gosh, that’s beautiful.

Narrator: Yeah, that was a beautiful snake. Even though Mark and Henry Marindin walk these paths more than a century apart, Mark speaks of his predecessor like a colleague or a friend. His eyes scan the greenery as we approach the cliffside and I try to see what he sees: all the stories and layers that are held in this landscape. We walk not only with the milk snake that crosses our path, but also with the memories of all these people who’ve observed the same scene. These figures of the past hold the key to interpreting what is to come. Marindin and the colonists were preceded by the people of the Wampanoag Nation, who inhabited Cape Cod for more than 12,000 years. Much of the knowledge these people held has been lost to the sands of time.

Mark: Let's think about the indigenous people. It's kind of phenomenal. You know, here we are, we're so proud of ourselves, we have a hundred years of observations. But—and then we use these maps, we have 400 years of maps. But, you know, when did the first people come here?

Narrator: We still don't know everything. But we do know that Cape Cod has not been stagnant since its creation 15,000 years ago in the aftermath of the last glacial period. So, we’re not going to make another Cape Cod, at least not in our lifetimes. Mark’s maps tell stories, but they aren’t tall tales. These stories contain lessons and messages for the current inhabitants of Cape Cod and all of those yet to come. There are physical consequences for the changes captured and foretold by GIS analysis. I stood with Mark on the edge of a 30-foot cliff, overlooking the blue watery horizon while he described the power and duration of these grand forces of nature. Behind us, an old shed labelled “Wave Observation Lab” is a lesson in adaptation.

Mark: So, the shed was originally there.

Narrator: Right. In the water.

Mark: And we just jacked it up and put rollers under it and just pulled it back.

Narrator: Mark was saying that the wave observation shed has been relocated several times since its creation in 2005 to accommodate the rapid rate of erosion. In order to continue to enjoy the natural spaces we love and to live in a warming world, we have to adapt to changes, such as sea level rise and erosion. If we heed the stories, we can become better stewards of the land and respect and protect our neighbors in the process. Mark’s work has already informed strategic park management decisions and improved understanding of coastal change. Beyond his lifetime, Mark might inspire a future technician, scientist, or artist to look at the landscape and see a collage of historical and scientific portraits, all depicting the same vista. Like him, they might see all its beauty, its evolution, and its delicate but hopeful future. Do you think about the legacy of what you're doing now? Or do you think about that often?

Mark: No, I don't, but that would be a dream. That'd be the dream—that there is a legacy.

Narrator: Thanks for listening to Stewardship Savvy. This special episode was written and produced by me, Colleen Keenan. If you want to learn more about the Cape Cod National Seashore, or how the park service is studying and protecting public lands, there’ll be resources linked in the show notes.

Our first episode of Stewardship Savvy features Mark Adams, a GIS specialist at Cape Cod National Seashore who has been with the National Park Service since 1991. In this episode, we follow Mark into the history of coastal change at Cape Cod, and the history of GIS (geographic information system) technology, as he's seen it.