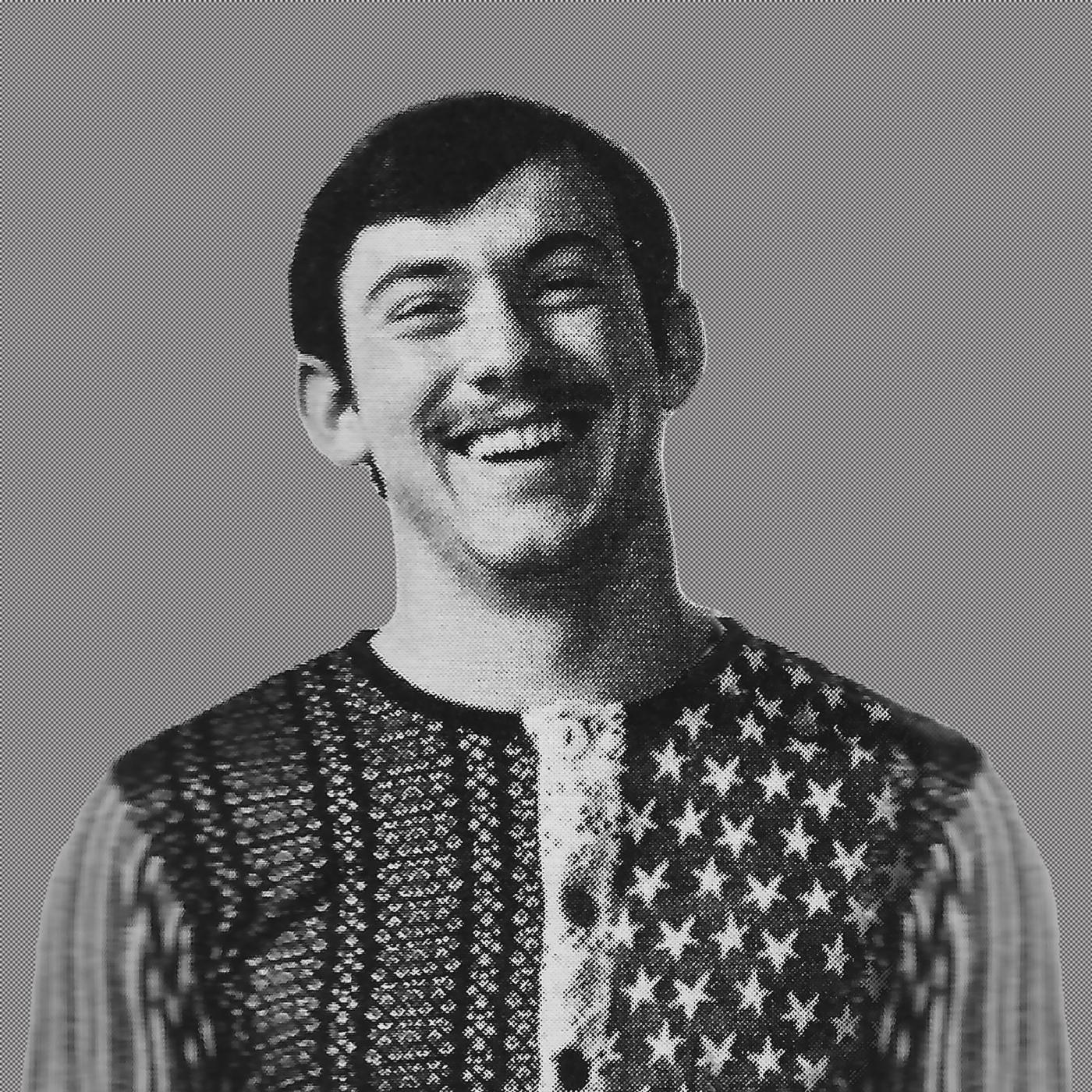

11. C.E. Dugdale

Transcript

David: Good morning Dr. Dugdale, good to have you here with us. Why don't you start us off today by telling us a little bit about yourself, your background. C.E. Dugdale: Thank you very much, David. Well, I'm a native of Louisiana. I was born and reared in a little village of Sibley, north of Choudrant, Louisiana and I don't know whether people know where Choudrant is. And I was born in 1897 on a farm near Camp Alabama. My father was English from sunny Devon. He came to this place over there. He had a brother and two uncles in this country and he bought some land there in the, on a hill farm. He paid $2 and 50 cents an acre for it. About 10 years ago, a sister of mine sold some of that land for $250 an acre. And I thought she didn't get enough at that time. We were on a small farm ,north Louisiana farm, hill farm, and the going was a little rough in those days. My memories of course are school and church primarily. They were the centers of our life. And I started a school when I was five years old. At the end of that year, the teacher very unadvisedly promoted me to the third grade. The next year, there was a new teacher there who demoted me to the second grade, very much to my disappointment. I attended this rural school, it was a two room school until the high school was established in Choudrant. And I was in the second graduating class of the Choudrant High School, 1916. And at that time, since the school here, the state normal [inaudible 00:02:03] was considered the teacher training institution in the state. I enrolled here because I intended to become a teacher. I remember I had a cousin, Velma O'Neal who was here at the same time. And on Friday evening, we had a picture show in the auditorium on the second floor of Caldwell hall. Well, Velma and I went together to this picture show and I sat with Velma. There was some 50, a hundred girls. I mean, men and the rest were girls. And I was there talking with Velma and somebody tapped on the shoulder. It was the Dean of Women informing me that men and women did not sit together at the picture shows at the normal school. And I had to get up and move down with the 20 or 30 men who were there at this show. Oh, this was in 1916 that I came to the state normal. And after I graduated, of course, it became a college very shortly thereafter. I was in about the second graduating class with a degree here from this school. And then I became a high school principal and was served in that capacity for several years. And every time, every summer during that period, I was given a position at the normal college. Mr. Royal was a good friend of mine, a very dear friend whom I remember with a great deal of pleasure and joy. He gave me a position every summer and I taught here and it was during the summer of 1926 I was teaching here that I became ill and had surgery. And of course there's a rather sad story. After that surgery, I was ill for a number of years and I was in the veteran's hospital. And of course I, that means that I had spent some time in the service during World War One. I would never have been drafted because I was a little too young to be drafted at that time, but I did volunteer and got in just for a little while. And the federal government of course had veterans hospitals for people in my situation. And it was my misfortune to be at a veterans hospital for some time. But I am very thankful that there was initiatives of that kind to take care of such people. David: That's true. C.E. Dugdale: Well after I got out of the hospital, was discharged in 1930, I decided that graduate work was in store for me. It was the best course I could follow. And I went to the University of Texas and registered at the Stephen F. Austin Hotel. And about one o'clock that night, I was seriously ill, called for a doctor. And the result was that I never got to register. I had to come home and lost a whole semester and went back at midyear. Well, I intended to register in Mathematics to do graduate work in Mathematics. It happens that at midyear, there was not a single graduate course available for me. And there I was, had already lost a semester and now could not get graduate Mathematics that I needed for the second semester and you could imagine how disappointed I was. And there I was talking about my disappointments, not being able to get the Mathematics and a Dean who was listening nearby said, by the way, I noticed that you were qualified in English. What about studying English? And I said, "am I"? I had no idea I was. And he talked me into that. And he said, you can get back into Mathematics if you don't find this interesting. But I got some of the best men that I've ever met in my life as teachers, Dr. Calloway, Dr. Law, Dr. Griffith. And I continued in English until I got my Master's. And then I was asked whether I would continue for my Doctorate. And I said, yes. And I was given a position as teacher there while I got my Doctorate and incidentally, I took Mathematics as a minor. And one of the finest men in Mathematics with international reputation, Professor Van Den Bergh was talking to me. I'd had courses with him ever since I had been there, and he asked me whether I would continue for my Doctorate. And I told him yes. And he volunteered to give me a position in Mathematics if I wished to continue my doctorate. Well, I had just accepted one in English. And though mathematics was my first love, I have never regretted getting into English and I have thoroughly enjoyed teaching it ever since I talked there for 10 years while I was getting my Doctorate. And incidentally, when my father, when I graduated, got my doctorate, he came down to Austin and my mother and father and a friend of his was talking with him, Mr. Lindsay and father said "well, I'm going to Austin, Texas. My son is graduating". Mr. Lindsay said, "my heaven is that boy still going to school"? So I could understand that I went to school much of the time until I was about 40 years old, you see. David: How did you come about coming back to [inaudible 00:07:52] C.E. Dugdale: I came to Southwestern in Lafayette and taught there for a year and the Principle here, I mean, the President here at the college, a good friend of mine, Joe Farah came down and asked our President whether he would release me to take the headship of the department of languages up here. I didn't see Joe Farah on his visit down, I didn't know he had come, but our President down there called me in shortly after and assured me that he would release me if I cared to go. And after all the transactions I finally got here, mainly because I know the people here, I had many friends in this area and I knew that I would enjoy living in [inaudible 00:08:35] and I certainly have enjoyed it. David: What are some of the things that you did, say, you said you were growing up around Sibley. I'm a little bit familiar with that area around camp Alabama it means a lot, especially, I guess, us Presbyterians. C.E. Dugdale: Yes. David: But what are some of the things you did around there growing up? Did you, were you able to fish or hunt or- C.E. Dugdale: oh yes. David: Were you much taken up with farm duties? C.E. Dugdale: Well, I certainly did that. It was a very busy time. We were all very busy, but my mother and father enjoyed fishing, though he was an Englishman. My mother was reared and her father enjoyed fishing. I used to go fishing with my granddad a great deal. Of course it was on a local stream and we fished with cane poles and caught Catfish and Brim mainly, sometimes Bass, but principally Brim and Catfish. And we thoroughly enjoyed those fish fries that we would have, community would join very frequently in fish fries. And we always were confident enough to be dependent. We depend upon catching the fish. And as I recall, we always did. David: Still doing that to an extent [crosstalk 00:09:49] C.E. Dugdale: Oh, yes I am. But we have a camp out on Celine. It really belongs to my sister and brother-in-law, but we use it 10 times more than they do and we thoroughly enjoy it. David: Well Dr. Doug, we really want to thank you for joining us on memories today. C.E. Dugdale: It's a very great pleasure to meet you, David.

Dr. C.E. Dugdale: Born in 1897 on a farm. His father was English and brought some land. He primarily remembers school and church as the main focus of his life. He intended to become a teacher, worked at Normal College every summer. Earned his doctorate in English.