Last updated: September 26, 2023

Place

Wilmington, North Carolina

East Carolina Digital Collections

In the first half of the twentieth century commerce expanded in Wilmington, North Carolina. However, the Great Depression ravaged the regional economy and placed many people out of work. The Wilmington Relief Association, formed by local citizens in the direct aftermath of the stock market crash, addressed the issue of unemployment by subsidizing the cost of public works projects. The opening of the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company in 1941 is what ultimately revived the region’s economy during the Second World War, transforming Wilmington into the “The Defense Capital of the State.” Residents from around North Carolina migrated to Wilmington to seek employment at the shipyard or with other defense industries located in or near the city.

By January of 1941, Great Britain was in desperate need of supplies, but the U.S. lacked the number of merchant vessels needed to transport cargo overseas. At the behest of President Roosevelt, the U.S. Maritime Commission ordered the construction of two hundred new ships. The country lacked the infrastructure to support this demand, so the Maritime Commission developed a cash program to construct new shipyards along the nation’s coasts. The agency awarded contracts to shipbuilding companies in the South to stimulate the region’s economy and take advantage of the abundance of natural resources, large labor force, and warm climate.

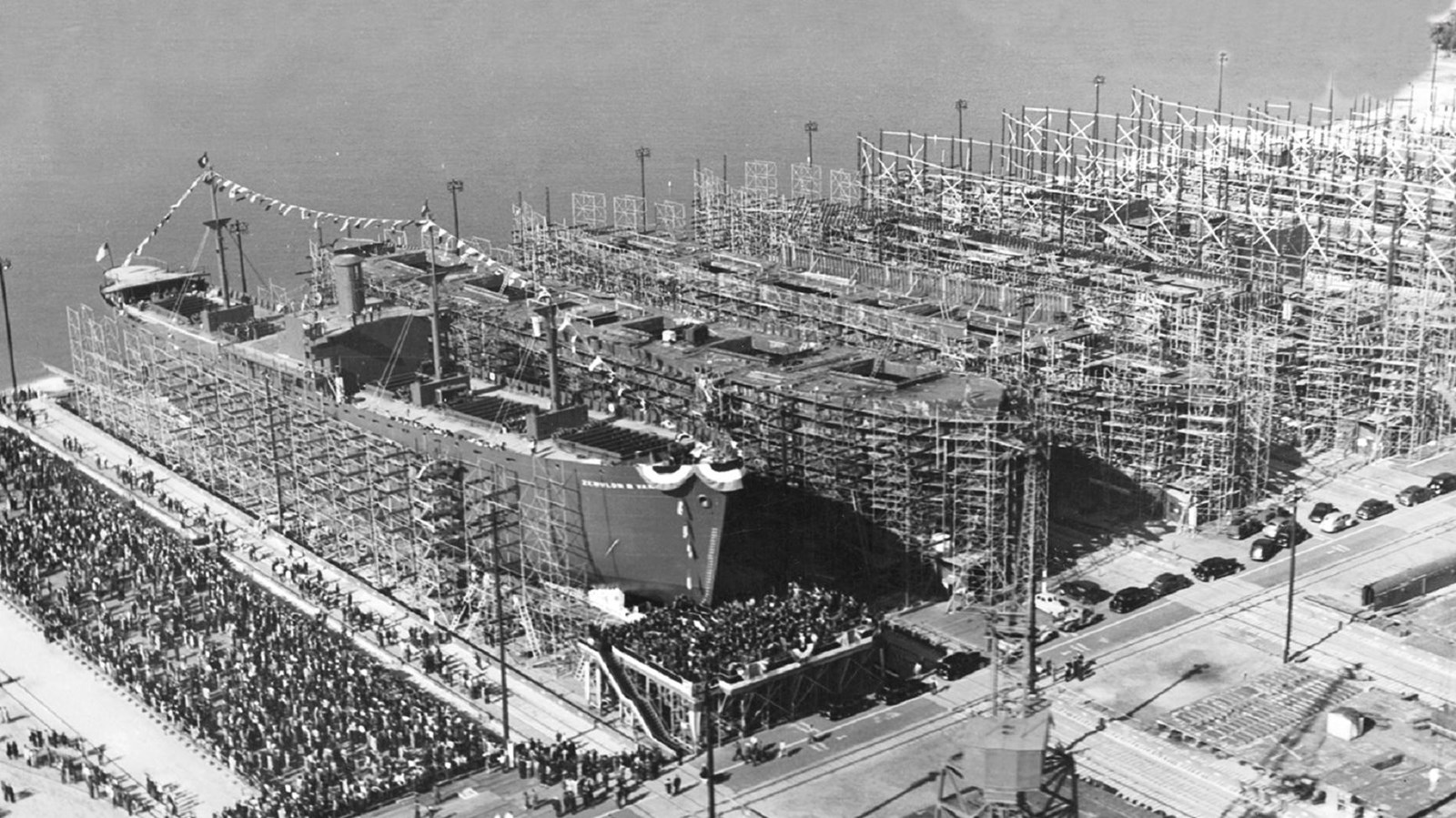

After receiving approval from the Maritime Commission, the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company commenced construction on a new shipyard along the east bank of the Cape Fear River on February 3, 1941. Executives of the company established a subsidiary, the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company, to operate the plant. The plant transformed Wilmington into an industrial hub and spurred internal migration that resulted in the city’s population increasing from 33,000 to 50,000. By 1943, the apex of national home front mobilization efforts, the shipyard employed approximately 20,000 people. Of those 20,000 employees, 1,628 were women and 6,000 were African Americans.

The company’s first female workers served as tool checkers, but eventually many were able to ascend to more skilled jobs, such as welding, operating woodworking machines and drill presses. African Americans employees worked as riveters, riggers, drillers, and shipwrights, amongst many other skilled positions. A shipyard hiring this number of African Americans was unparalleled in the South. While integrated crews existed in the plant the company mandated the segregation of employee facilities, such as the cafeteria and lockers. Shipyard employees, who received national recognition for their efficiency and advanced techniques, built 234 ships between 1941 and 1946. The Carolina Shipbuilding Company was one of ten shipyards in the country that specialized in the construction of Liberty cargo vessels. These ships transported ammunition, tanks, vehicles and other military supplies during the war.

While thousands of citizens secured jobs in Wilmington at the shipyard and other industrial sites, the increase in population stressed the city’s infrastructure and produced a housing and food shortage. The federal government intervened to alleviate the issue by constructing 1,700 housing units. A lot adjacent to the shipyard was converted into a trailer camp for employees. Families and individual employees unable to secure housing were forced to construct makeshift shelters using tents and old railroad cards.

The USO club in downtown Wilmington at Second and Orange became a popular off-duty site for hundreds of thousands of white service people stationed at bases in neighboring cities, such as Camp Davis, Camp Lejeune, and Fort Bragg. When it opened in 1941, volunteers at the club organized radio broadcasts, dances, theatre, childcare, and art exhibits for approximately 35,000 servicepeople per week. The basement was converted into a dormitory that could accommodate up to 600 men. Jim Crow laws in the South restricted these facilities to only white servicemen and women. A club for African American service people was constructed fifteen blocks north on Nixon Street. The USO club at Second and Orange still stands and is now the Hannah Block Historic USO/Community Arts Center. Unfortunately, the club for African American servicemen was demolished after the war. It was sold to the Boys Club in 1947, and the construction of a new building on the site occurred sometime around 1978.

After the war, local preservation efforts encouraged by the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 led to the listing of most of downtown Wilmington in the National Register of Historic Places by 1974. The USS North Carolina, which currently rests in the Cape Fear River, received a National Historic Landmark designation on January 14, 1986.

In September 2020, Wilmington, North Carolina was designated an American World War II Heritage City.

The American World War II Heritage City program recognizes the war time contributions and current efforts to preserve and memorialize the home front in cities across the country. Created by the John Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act of 2019, and coordinated by the National Park Service, the program tells the home front stories of cities that best reflect one of the most transformative eras of our nation’s history.