Last updated: September 23, 2021

Place

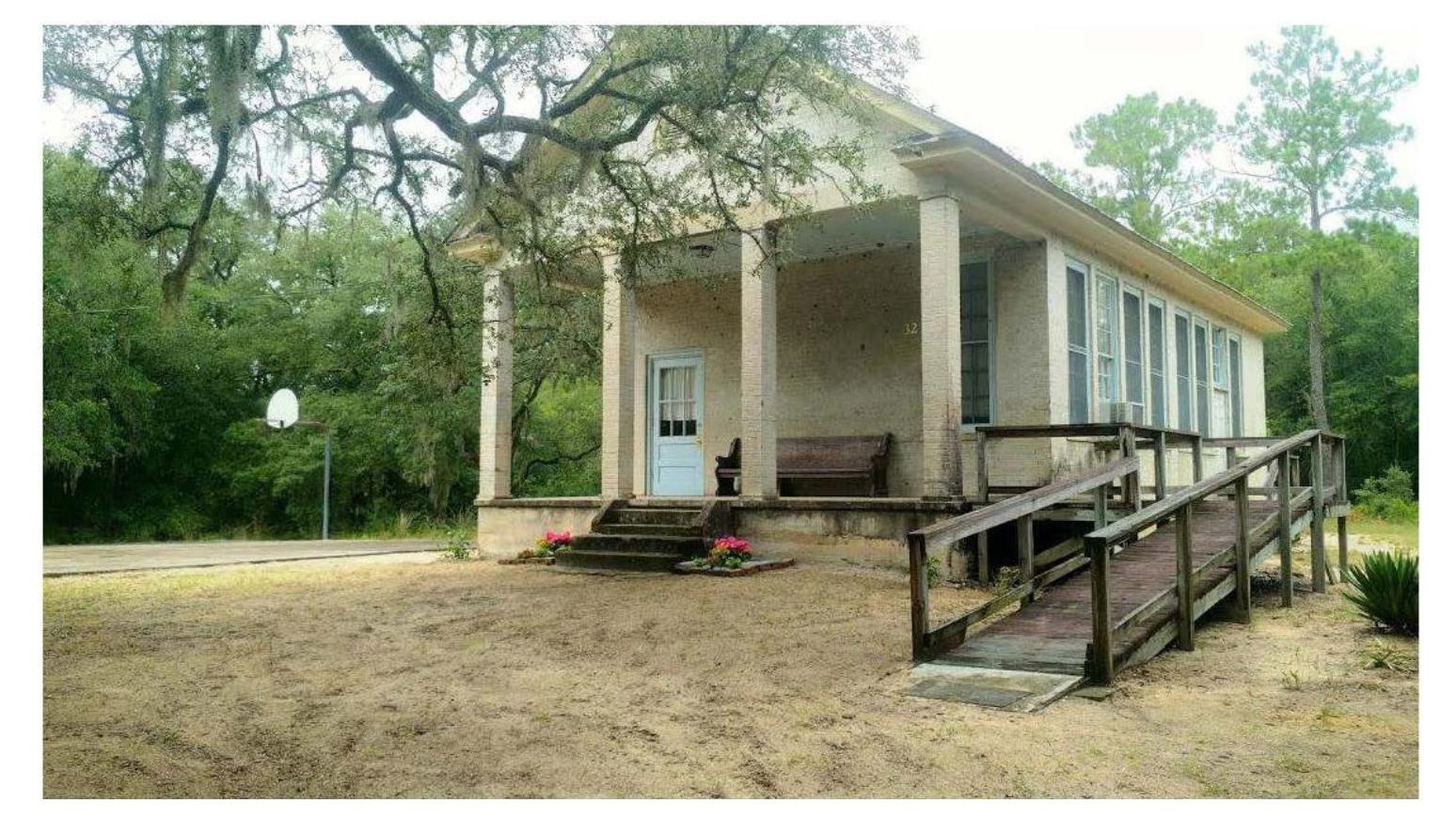

South Carolina| Sandy Island School

Photograph by Haley Yarborough, courtesy of the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office

The Sandy Island School on Sandy Island, South Carolina is significant to the story of African American civil rights in South Carolina because it served as the central location for the islander community’s activism for political representation and cultural preservation. The school embodies the self-sufficiency of the Sandy Island community in the face of unequal and scarce educational resources for African Americans throughout the twentieth century. Through the islanders’ collective determination and action, students received a quality education in the face of meager resources, enabling them to flourish in their chosen careers off the island.

The construction of Sandy Island School, the salaries of its teachers, and even living quarters for the faculty were financed entirely by a wealthy northern couple, Archer and Anna Hyatt Huntington. In 1929, the Huntington’s purchased four former plantations and additional acreage on Sandy Island. Archer Milton Huntington (1870-1955) was a poet, scholar, and avid supporter of the arts. Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973) was an award-winning sculptor who came from a family that valued higher education and the arts. The Huntington’s acquisition of land along the Waccamaw Neck was part of a wider trend of wealthy families purchasing abandoned or financially strapped former plantations in the coastal south after the collapse of the plantation rice economy. On Sandy Island, the Huntington’s built the school, as well as an identical (now demolished) school near Brookgreen Plantation, in addition to a medical clinic, and a still-extant church, Brown Chapel.

Prior to the building of Sandy Island School, education on the island took place in residents’ homes or in churches, with the islanders paying the teachers’ salaries. Students only attended school for four or five months out of the year because families needed their children during the planting and harvesting season, and the community could only afford the teachers’ wages for a portion of the year. Over time, the teachers who taught on Sandy Island became an important part of the community, including a man who would become the last African American member in the South Carolina House of Representatives until 1970, John William Bolts. In fact, Sandy Island served as one of the largest African American voting blocks in Georgetown and unanimously elected Black representatives to the national and state legislators until Jim Crow voting officials removed it as a voting precinct in 1902.

Once the school was constructed, Sandy Island’s children went to school for a full nine-month term. One of the first teachers and first principal of the new school was Doland Bland, a graduate of Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina. According to employment records, another early teacher was S.W. Tucker, who lived in the teacher’s cottage from September 1938 to May 1942. To staff the school, the island’s leaders often called upon college-educated community members like Emily Collins Pyatt, a graduate of Benedict College, who taught on the island for eleven years. Education at the school reflected the religious values of the community, and many former students and Sandy Island residents, such as Laura Herriot, recall teachers beginning each school day with a prayer and religious song.

While Sandy Island was and remains an island community, the educators on Sandy Island were far from isolated. The principal and teachers of the Sandy Island School were heavily involved in the organization and execution of the Brookgreen Welfare Conference throughout the 1930s and 1940s, which was founded by Seymour Carroll, chairman of the South Carolina Natural Resources Commission. The Brookgreen Welfare Conference was a statewide and regional conference that brought together volunteer health practitioners, who provided care for residents, and African American political leaders from across the state. Bland or Miles Bogan, principal of Brookgreen School, often chaired the organizational committee for the conference. The Sandy Island School children performed for the conference attendees, and the Brookgreen and Sandy Island schools hosted several of the conference’s sessions. Horry and Georgetown County schools both offered holidays to their employees and students to attend the conference.In what Andrew Young has asserted was the very foundation of the Civil Rights Movement, African American political leaders throughout South Carolina began organizing adult education schools called Citizenship Schools to overcome the literacy test hurdle.

In the late 1950s, Sandy Island School served as a host site for the Georgetown County Adult Negro School Program, a Citizenship School with close ties to the adult educational efforts on Johns Island. As such, Sandy Island has historic significance for its association with this movement of literacy and political empowerment among local African Americans within the region. The existence of such adult schools within Georgetown County, and the rest of South Carolina, has previously been undocumented. The Georgetown County Negro Adult School’s program was organized in a similar manner to the Citizenship Schools on Johns, Edisto, and Wadmalaw Island, which were also all active PDP precincts.In the late 1950s, Beatrice Funnye, current resident of Plantersville, SC, was a student in the Georgetown County Negro Adult School program in Plantersville, and her teacher was former Sandy Island School teacher and principal Emily Collins Pyatt. She remembers learning the South Carolina Constitution and the election process during the evening classes. However, there were also basic concepts such as general math taught.

During this same period, Sandy Islander Yvonne Tucker-Harris recalls helping her grandmother complete math assignments for the Sandy Island’s adult classes. Central to the mission of the adult school, however, was voter registration. According to Funnye, Plantersville’s civic leaders told the community to attend the adult school to “learn how to read so you know how to vote.”

Through the efforts of the NAACP, Progressive Democratic Party, and the Georgetown County Negro Adult School program, the total number of registered voters in Georgetown County increased from 5,608 to 10,366 (85%) between 1958-1962. Through these adult education courses, Sandy Island rekindled its political power hard-won during Reconstruction. Sandy Island’s seniors, who were past school age when the Sandy Island school was built, passed the challenging literacy tests each year to cast their vote—a practice continued until this day. Sandy Island and Waccamaw Neck activist and voting precinct volunteer Genevieve Peterkin described them as the most “civic-minded people” with a nearly 100% turnout in every election, and potential candidates would noticeably appeal to island community leaders, such as Prince Washington, for the islanders’ vote.

The Sandy Island School was added to the African American Civil Rights Network (AACRN) in September 2021.

The African American Civil Rights Network recognizes the civil rights movement in the United States and the sacrifices made by those who fought against discrimination and segregation. Created by the African American Civil Rights Act of 2017, and coordinated by the National Park Service, the Network tells the stories of the people, places, and events of the U.S. civil rights movement through a collection of public and private resources.