Last updated: February 23, 2023

Place

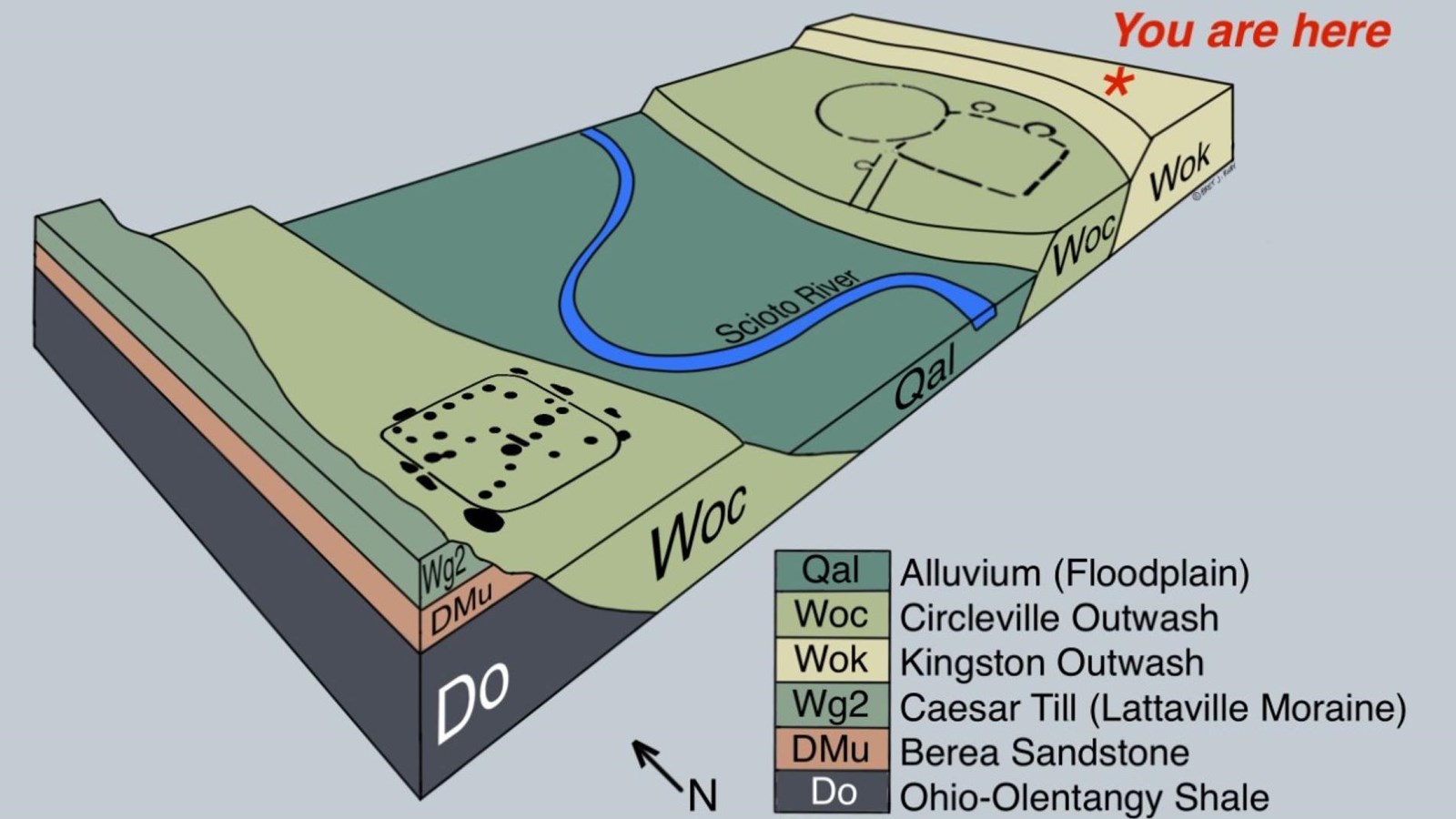

Scioto Valley Geology

NPS Illustration/Bret J. Ruby

The hills you see in the distance are the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. The hills are made of sedimentary sandstones and shales laid down more than 325 million years ago during the Devonian and Mississippian geologic periods when this part of the Earth was covered by shallow seas (DMu: Berea Sandstone; Do: Ohio-Olentangy Shale). Later, the hills were pushed up when the tectonic plates underlying the African and North American continents collided (the Alleghanian orogeny, 325-260 million years ago). Those mountain-building events took place long before humans walked the earth.

18,000 years ago, the spot where you are standing here at Stop 3 would have been covered by glacial ice. The ice even covered some of the hills on the western horizon. A warming trend caused the glacier to retreat northward leaving behind loamy soils on the distant hilltops (Wg2: Caesar Till/Lattaville Moraine). The meltwaters also carried sands and gravels here to form the landform you are standing on (Wok: Kingston Outwash terrace). After a brief re-advance about 17,200 years ago, the glaciers resumed their retreat and the meltwaters cut down into the Kingston Outwash and formed the wide, flat terrace below you (Woc: Circleville Outwash terrace). The Scioto River has been meandering across the modern floodplain since the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,600 years ago (Qal: Alluvium). We know American Indians were here at least 10,000 years ago because archeologists found flint knives and dart points of that age in the fields below you.

2,000 years ago, American Indians chose these glacial outwash terraces to build their largest geometric earthworks. Just below you are the conjoined circle, square, and parallel walls of the Hopeton Earthworks. Just across the river to the west, on the same terrace, is the Mound City Group earthworks with at least 25 mounds surrounded by an earthen wall and eight dug holes. Other large earthworks are found on outwash terraces both upstream and downstream from here. The ancient architects chose these broad, flat, well-drained and flood-free landforms as building sites for their greatest monuments.

Today, these glacial outwash terraces are valuable sources of sand and gravel for the construction industry. Ohio ranks among the top ten producers in the country. You can see an active mine in the distance just beyond the Hopeton Earthworks. When that mine opened in the 1970s it threatened to destroy the earthworks. Local people started a movement to protect the earthworks, and Congress designated Hopeton Earthworks as a national park in 1980.

18,000 years ago, the spot where you are standing here at Stop 3 would have been covered by glacial ice. The ice even covered some of the hills on the western horizon. A warming trend caused the glacier to retreat northward leaving behind loamy soils on the distant hilltops (Wg2: Caesar Till/Lattaville Moraine). The meltwaters also carried sands and gravels here to form the landform you are standing on (Wok: Kingston Outwash terrace). After a brief re-advance about 17,200 years ago, the glaciers resumed their retreat and the meltwaters cut down into the Kingston Outwash and formed the wide, flat terrace below you (Woc: Circleville Outwash terrace). The Scioto River has been meandering across the modern floodplain since the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,600 years ago (Qal: Alluvium). We know American Indians were here at least 10,000 years ago because archeologists found flint knives and dart points of that age in the fields below you.

2,000 years ago, American Indians chose these glacial outwash terraces to build their largest geometric earthworks. Just below you are the conjoined circle, square, and parallel walls of the Hopeton Earthworks. Just across the river to the west, on the same terrace, is the Mound City Group earthworks with at least 25 mounds surrounded by an earthen wall and eight dug holes. Other large earthworks are found on outwash terraces both upstream and downstream from here. The ancient architects chose these broad, flat, well-drained and flood-free landforms as building sites for their greatest monuments.

Today, these glacial outwash terraces are valuable sources of sand and gravel for the construction industry. Ohio ranks among the top ten producers in the country. You can see an active mine in the distance just beyond the Hopeton Earthworks. When that mine opened in the 1970s it threatened to destroy the earthworks. Local people started a movement to protect the earthworks, and Congress designated Hopeton Earthworks as a national park in 1980.