Last updated: September 20, 2024

Place

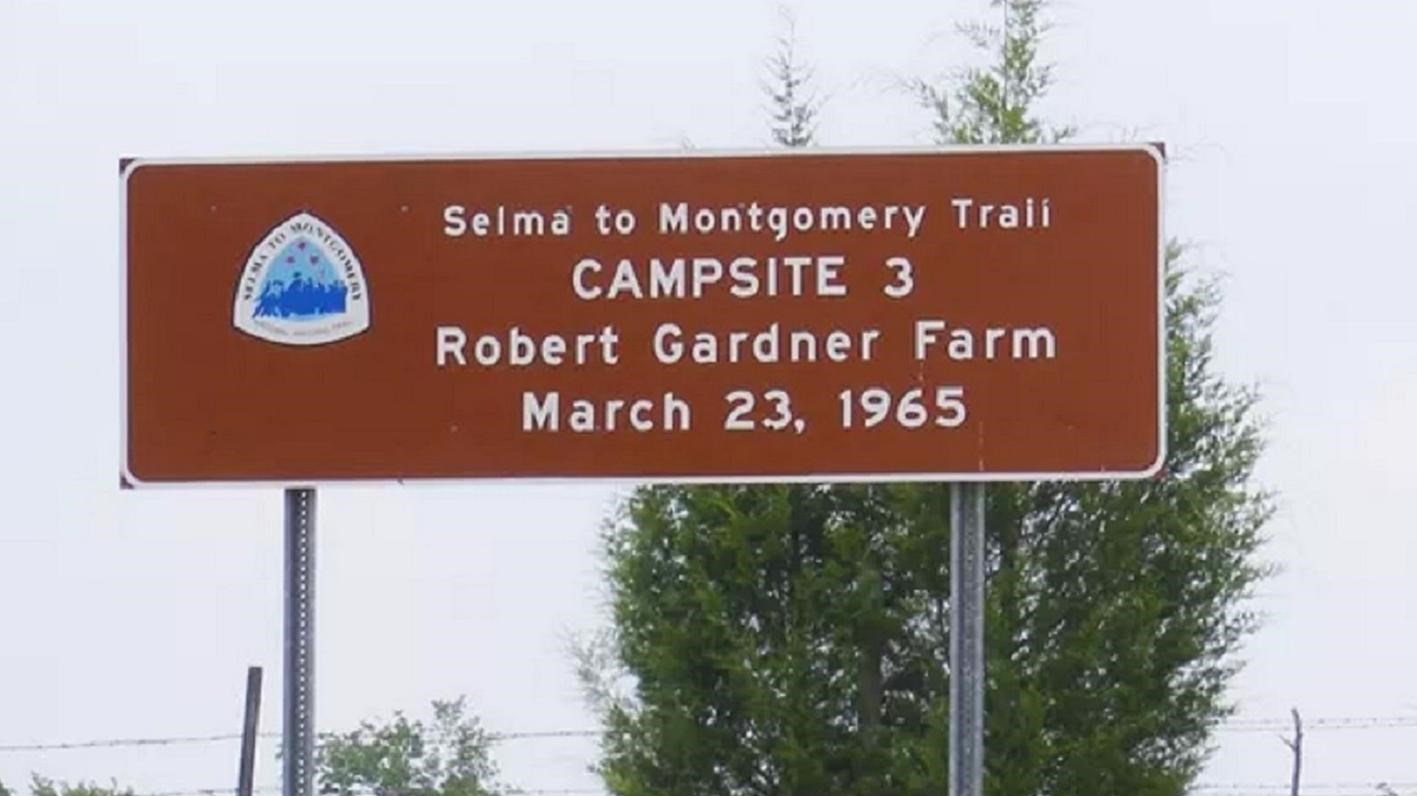

Robert Gardner Farm (Campsite 3)

NPS Photo

Quick Facts

Significance:

Third campsite along the historic Selma to Montgomery voting rights march in 1965.

On the evening of March 23rd, 1965, the farm of Black farmer Robert Gardner became the third campsite for the Selma to Montgomery March. Located along U.S. Highway 80, this site provided a temporary refuge for the activists enduring their five-day, 54-mile trek to the Alabama State Capitol. After a day of relentless rain and drizzle, the marchers were soaked and exhausted, sought shelter at the farm of Robert Gardner, a Black farmer and resident of Lowndes County.

The marchers found the ground muddy and difficult to traverse. Gardner and other local volunteers put hay down to try and cover the mud. Tents were pitched for the marchers but provided limited protection from the elements. After dinner, which was generously provided by students from the Tuskegee Institute, some of the marchers attempted to rest on donated air mattresses, though many awoke the next morning to find them deflated. Others found shelter on the farmhouse porch, seeking relief from the unforgiving weather.

Despite the harsh conditions and the ever-present threat of violence, nightly rallies featured songs, speeches, and prayers, fueling the determination of the participants to continue their journey toward justice. Local residents, at great personal risk, contributed food and assistance, reinforcing the deep sense of solidarity that sustained the movement.

Robert Gardner was married to Mary, an educated schoolteacher in Lowndes County. The family lived off their land and raised their own food, but their support of the march did not come without consequences. Before the marchers arrived, local disgruntled White residents who were against the Selma to Montgomery March had attempted to bribe the family. When the attempted bribery failed, the local White neighbors threatened the family with violence, and phone and power lines to the property were cut. Shortly after the marchers had left the property, a National Guardsman was patrolling the area and found a White neighbor with a scoped rifle pointed at the family farm. The neighbor was informed by the soldier if anything happened to the Gardner family, he would be held as the prime suspect.

The marchers found the ground muddy and difficult to traverse. Gardner and other local volunteers put hay down to try and cover the mud. Tents were pitched for the marchers but provided limited protection from the elements. After dinner, which was generously provided by students from the Tuskegee Institute, some of the marchers attempted to rest on donated air mattresses, though many awoke the next morning to find them deflated. Others found shelter on the farmhouse porch, seeking relief from the unforgiving weather.

Despite the harsh conditions and the ever-present threat of violence, nightly rallies featured songs, speeches, and prayers, fueling the determination of the participants to continue their journey toward justice. Local residents, at great personal risk, contributed food and assistance, reinforcing the deep sense of solidarity that sustained the movement.

Robert Gardner was married to Mary, an educated schoolteacher in Lowndes County. The family lived off their land and raised their own food, but their support of the march did not come without consequences. Before the marchers arrived, local disgruntled White residents who were against the Selma to Montgomery March had attempted to bribe the family. When the attempted bribery failed, the local White neighbors threatened the family with violence, and phone and power lines to the property were cut. Shortly after the marchers had left the property, a National Guardsman was patrolling the area and found a White neighbor with a scoped rifle pointed at the family farm. The neighbor was informed by the soldier if anything happened to the Gardner family, he would be held as the prime suspect.