Last updated: June 11, 2024

Place

Parade Ground Tour Stop 8: World War I

National Archives and Records Administration

Quick Facts

Amenities

1 listed

Wheelchair Accessible

Built at the same time as the double infantry barracks, this building served as the post’s administrative headquarters beginning at the turn of the century. As the United States entered World War I in 1917, Vancouver Barracks became an important regional headquarters, training and outfitting soldiers for operations both abroad and on the home front. This administrative building managed the operations of the more than 1,500 soldiers who lived at the post, while the barracks around it housed local volunteers and draftees before they were assigned to permanent units.

For new inductees like Martin Luther Kimmel, Vancouver Barracks was their first experience of active military life. As they completed their physical examinations and received vaccinations, Kimmel and other newcomers would have stayed in barracks like these, sharing the post with engineers from the three engineer training camps hosted during the war and the four permanent companies of infantry. Kimmel later remembered that seeing infantry drills on this Parade Ground was his “first real thrill of soldier life.”

This thrill, like the excitement of other new recruits, most likely faded as Kimmel experienced the harsh realities of the front. Wounded in France in August 1918, Kimmel spent the end of the war in overseas convalescent hospitals before returning to the United States in 1919. Others who began their journey at Vancouver Barracks would not return. Vancouver brothers Robert and Fred McEnany enlisted in the Oregon Third Infantry and spent several months here in 1917 before their mobilization to France as part of the 127th Infantry. The following summer, their parents received notification that both their sons had perished, two of the 50,000 US troops to die in the battles of World War I.

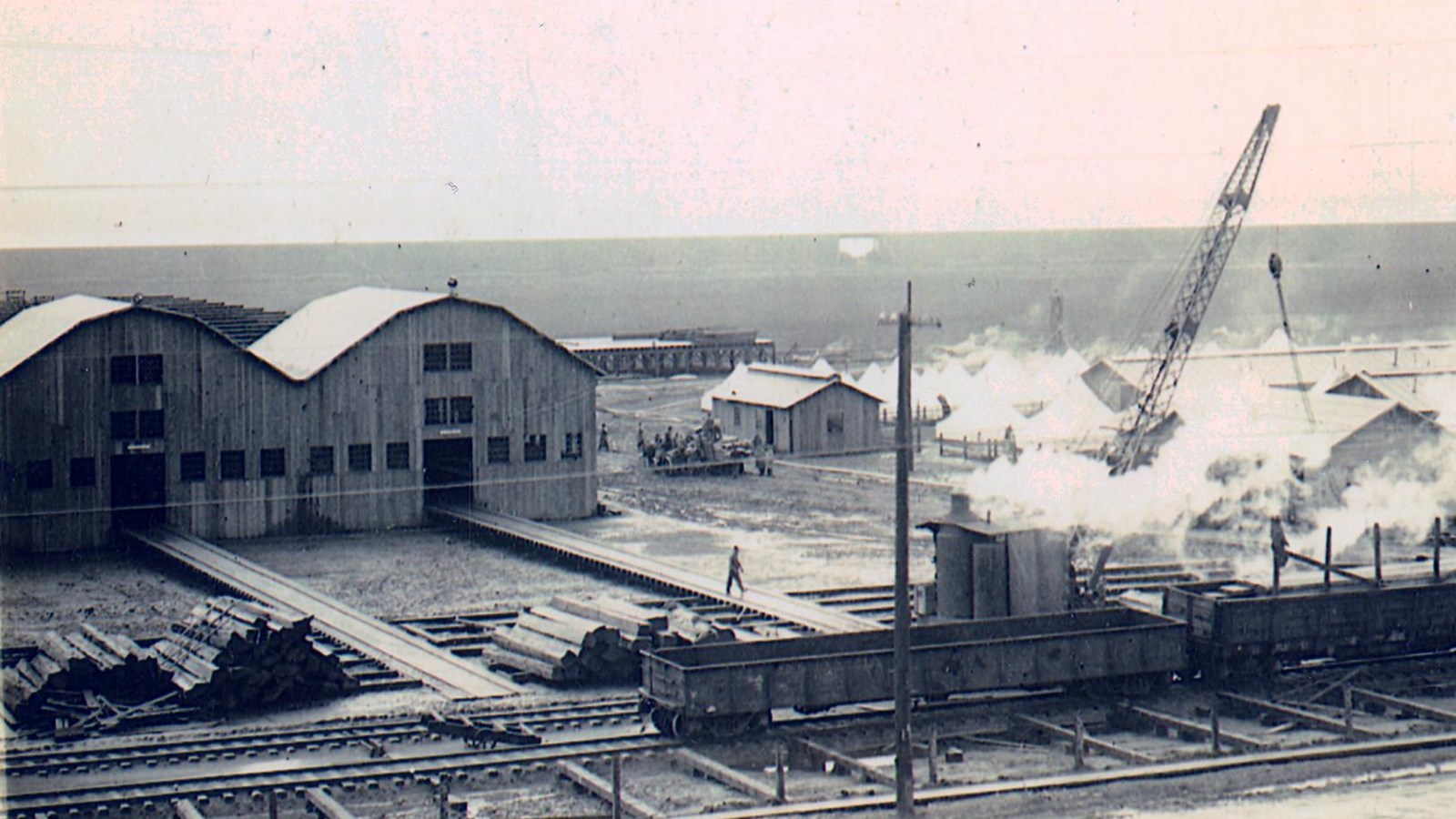

As some soldiers at the barracks prepared to go overseas, others aided the war effort from the Pacific Northwest. From 1917 to 1918, the Army’s Spruce Production Division (SPD) controlled the Northwest logging industry, employing over 30,000 soldiers to produce lumber for Allied ships and aircraft. In addition to operating logging camps throughout the Northwest, the SPD had its headquarters and main mill at Vancouver Barracks, located on the plain just south of here.

Beyond providing material, the creation of the SPD also lessened the influence of labor unions on the logging industry. Groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had organized for better working conditions in logging camps through labor strikes. Fearing a disruption to lumber production during wartime, the Army replaced most civilian employees with soldiers and required that both military and civilian workers sign a pledge to ensure continuous operations. However, new Army regulations also provided some of the improvements fought for by labor unions, such as an 8-hour workday and minimum sanitation standards.

In service from February to November of 1918, the mill alone was an enormous operation, employing over 5,000 soldiers and producing over 1 million board feet of lumber per day at its peak. Existing barracks like these were unable to accommodate this population surge, so most SPD soldiers lived in “tent neighborhoods” that were built just west of the main mill building.

If you would like to learn more about the SPD at Vancouver Barracks, Pearson Air Museum features exhibits on this chapter in barracks' history, including a scale model of the mill complex and a full-size replica of the tents where many workers lived.

When have you had to collaborate with others to achieve a larger goal? What was that experience like? How was it different than working alone?

For new inductees like Martin Luther Kimmel, Vancouver Barracks was their first experience of active military life. As they completed their physical examinations and received vaccinations, Kimmel and other newcomers would have stayed in barracks like these, sharing the post with engineers from the three engineer training camps hosted during the war and the four permanent companies of infantry. Kimmel later remembered that seeing infantry drills on this Parade Ground was his “first real thrill of soldier life.”

This thrill, like the excitement of other new recruits, most likely faded as Kimmel experienced the harsh realities of the front. Wounded in France in August 1918, Kimmel spent the end of the war in overseas convalescent hospitals before returning to the United States in 1919. Others who began their journey at Vancouver Barracks would not return. Vancouver brothers Robert and Fred McEnany enlisted in the Oregon Third Infantry and spent several months here in 1917 before their mobilization to France as part of the 127th Infantry. The following summer, their parents received notification that both their sons had perished, two of the 50,000 US troops to die in the battles of World War I.

As some soldiers at the barracks prepared to go overseas, others aided the war effort from the Pacific Northwest. From 1917 to 1918, the Army’s Spruce Production Division (SPD) controlled the Northwest logging industry, employing over 30,000 soldiers to produce lumber for Allied ships and aircraft. In addition to operating logging camps throughout the Northwest, the SPD had its headquarters and main mill at Vancouver Barracks, located on the plain just south of here.

Beyond providing material, the creation of the SPD also lessened the influence of labor unions on the logging industry. Groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) had organized for better working conditions in logging camps through labor strikes. Fearing a disruption to lumber production during wartime, the Army replaced most civilian employees with soldiers and required that both military and civilian workers sign a pledge to ensure continuous operations. However, new Army regulations also provided some of the improvements fought for by labor unions, such as an 8-hour workday and minimum sanitation standards.

In service from February to November of 1918, the mill alone was an enormous operation, employing over 5,000 soldiers and producing over 1 million board feet of lumber per day at its peak. Existing barracks like these were unable to accommodate this population surge, so most SPD soldiers lived in “tent neighborhoods” that were built just west of the main mill building.

If you would like to learn more about the SPD at Vancouver Barracks, Pearson Air Museum features exhibits on this chapter in barracks' history, including a scale model of the mill complex and a full-size replica of the tents where many workers lived.

When have you had to collaborate with others to achieve a larger goal? What was that experience like? How was it different than working alone?