Last updated: July 8, 2020

Place

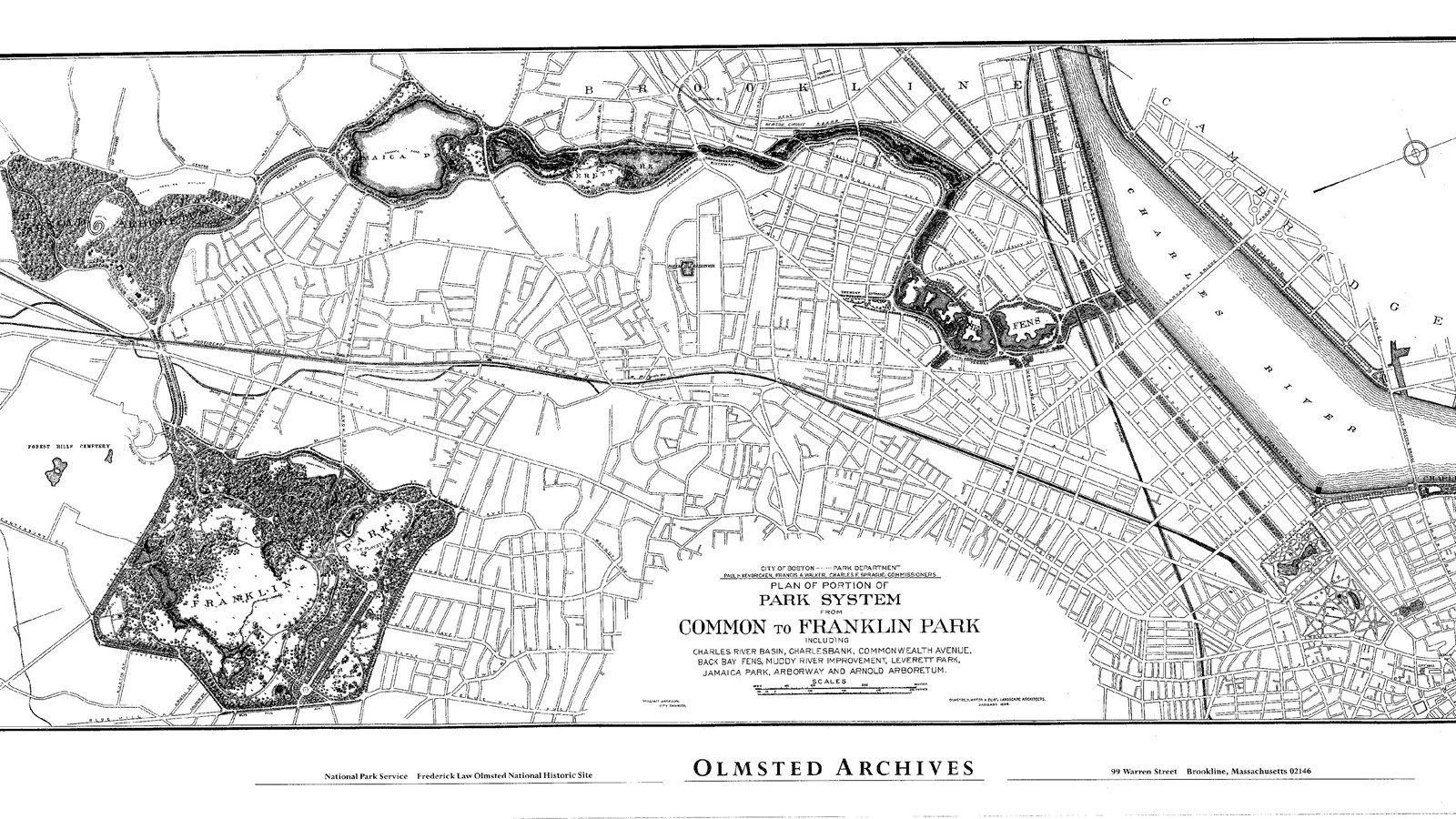

Olmsted Park System

By Boston Parks Department & Olmsted Architects, NPS Olmsted Archives, Public Domain.

As one of the first park systems created in the United States, Boston’s Olmsted Park System served as a model for metropolitan open space planning initiatives elsewhere. The nine distinct parks, later coined the “Emerald Necklace,” span seven miles from the historic center of Boston through various neighborhoods, connecting the city with nature and offering a wide range of experiences from sports areas to a zoo to garden walks. Not only does the Olmsted Park System provide various recreational outlets, but it also stands as a physical example of 19th century ideals on nature and conservation. Boston Common, Boston Public Garden, and Arnold Arboretum, all parks within the Olmsted Park System, are also included in this travel itinerary for their own contribution to Massachusetts conservation.

After the Civil War, communities inspired by the creation of Central Park spearheaded initiatives to create their own large, country parks for city dwellers. In Boston, the 50-acre Boston Common and the 24-acre Public Garden provided some parkland for the city, but these small areas of open space were clearly inadequate for the growing metropolitan area. Boston already had grown so much that a single large park in the center of the city proved impossible. Rural communities surrounding Boston encountered rapid development as well, making it increasingly difficult for urban residents to reach pastoral, wooded countryside outside the city.

By the late 1870s, several Boston area landscape designers had proposed versions of a Boston metropolitan park system, but ultimately Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.’s design was chosen. Instead of a single large park, Olmsted envisioned a series of smaller parks connected by parkways extending from Boston through its suburbs. The proposed park system created municipal open space by linking existing parks like Boston Common and Public Garden via Commonwealth Avenue with a variety of large and medium parks in the suburbs. Olmsted’s plan for the park system accomplished three purposes: it created a much needed and desired municipal open space in spite of land limitations; it connected newly annexed neighborhoods with Boston’s historic center; and it provided a variety of park types, each serving different recreational needs.

The first portions of the park system planned, Back Bay Fens and the Fenway, proved the most troublesome for the Boston Park Commission. Once a tidal swamp, the Fens served as a repository for sewage and was often violently flooded. Asked to solve the problems, Olmsted created informal parkland using swamp-like vegetation that could withstand the flooding. His solution to the Back Bay Fens stands as a great achievement in engineering and landscape design.

Anticipating the expansion of south Boston into more rural areas, Olmsted designed Franklin Park as a retreat for working class city dwellers who needed open park space. One of Olmsted’s masterpieces, Franklin Park is also the largest park and considered the “crowning jewel” of the park system. Even though work did not begin on Franklin Park until 1885, the space had held a place in park system designs ever since Benjamin Franklin generously bequeathed the funds to the city of Boston.

The final Olmsted designed parks in the system include Back Bay Fens (1879); Muddy River (1881); Olmsted Park (1881); Jamaica Park (1892); Franklin Park (1885); and the Arnold Arboretum (1872) for which Charles Sprague Sargent collaborated in the design. These parks, along with the others in the Olmsted Park System, stand as an outstanding example of multi-use open space and one of Olmsted’s finest projects. Users of the nine parks of the Olmsted Park System can play sports, visit a zoo, ice skate, hike, and just enjoy nature and admire the views. The parks offer a wide variety of natural and recreational activities year-round. Today, visitors can still enjoy the park system as Olmsted intended when he set out his designs over 100 years ago.

The Olmsted Park System is located in Boston and Brookline, MA extending from the mouth of the Muddy River south to Franklin Park. The parks are accessible by foot, car, or public transportation. For more information, visit the City of Boston’s Parks & Recreation Department website or visit the Emerald Necklace Conservancy website.

To discover more Massachusetts history and culture, visit the Massachusetts Conservation Travel Itinerary website.