Last updated: July 28, 2025

Place

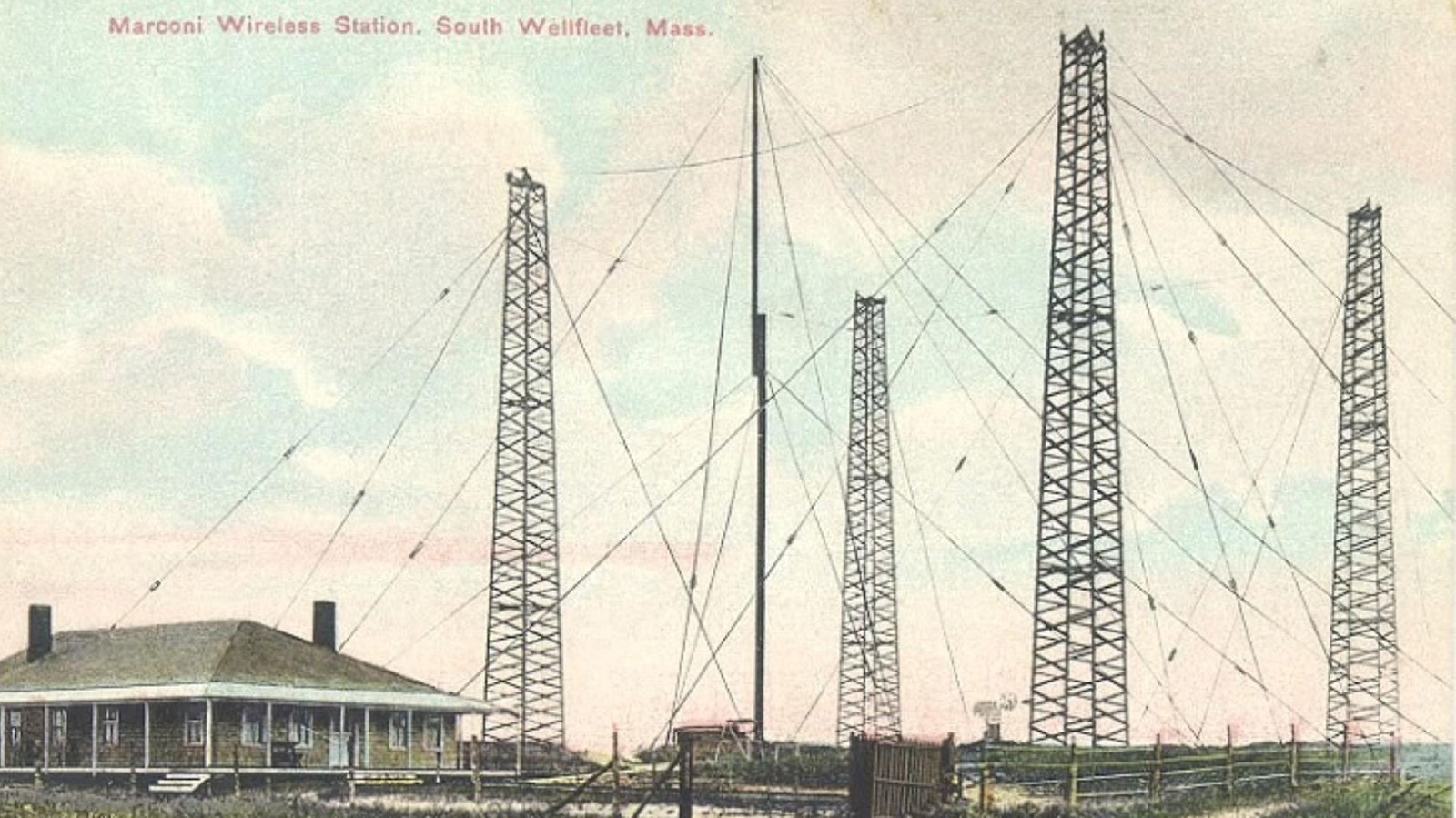

Marconi Station Site

NPS Photo

Benches/Seating, Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Information Kiosk/Bulletin Board, Parking - Auto, Picnic Table, Restroom - Seasonal, Scenic View/Photo Spot, Toilet - Vault/Composting, Wheelchair Accessible

The Birth of an Idea

The experiments of Heinrich Hertz inspired the idea. This German physicist first demonstrated the existence of electric and magnetic waves, and with this revelation young Guglielmo Marconi began dreaming of a way to send messages from transmitter to receiver without the aid of wires. In 1894 Marconi retreated to a top floor laboratory of his family’s Villa Grifone near Bologna, Italy, and at the age of twenty began his experiments in earnest. At first, Marconi used homemade equipment, testing and repeatedly modifying it, each time stretching to greater limits the distance that signals could be received from a transmitter. First it was 30 feet. Then it was one mile. Then it was twenty and fifty miles. By 1901, Marconi achieved a range of 200 miles. Wireless telegraphy was suddenly the rage of Europe – and then of America.

On December 12, 1901 in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Marconi raised a kite with an antenna dangling from it. He sought to prove that radio waves could cross the Atlantic. Through that hanging wire he heard the anticipated signal from across the ocean. The first transatlantic signal from England had been detected.

Spanning the Ocean

For Marconi the ‘great thing’ was to transmit wireless signals across the Atlantic. He built stations at Poldhu, England, Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, and South Wellfleet, Massachusetts. At this stage of wireless technology relatively long electromagnetic waves were used as signals. Transmitting great distances, therefore, required great sensitivity of receivers and tremendous power. Originally, huge rings of masts were installed to support the needed antennas. When storms destroyed them, they were replaced by sets of four wooden towers, 210 feet in height. Power requirements were tremendous. Keroseneburning engines produced 2,200 volts. When fed to a Tesla transformer, the voltage was stepped up to 25,000 volts – the energy needed to transmit longwave signals so far. It was from the Glace Bay station that the first successful two-way transatlantic wireless test message was sent on December 17, 1902.

Impacting Lives

January 18, 1903 the first public two-way wireless communication between Europe and America occurred. With elation, communiques from President Theodore Roosevelt and King Edward VII were translated into international Morse code at the South Wellfleet and English stations, respectively, and were broadcast.

Ocean-going vessels quickly adopted Marconi apparatus to receive news broadcasts, and soon ship-to-shore transmittals were a major operation. Business and social messages could be sent for fifty cents a word. The South Wellfleet station became the lead North American facility for this function. The station’s effectiveness was limited however, so broadcasts were made between 10 pm and 2 am when atmospheric conditions were best.

This brought little enthusiasm from local residents, who endured the sounds of the crashing spark from the great three-foot rotor supplied with 30,000 watts. The sound of the spark could be heard four miles downwind from the station. Eventually, the novelty of wireless telegraphy waned. However, the need for communication at sea remained high. Effective communication resulted in numerous sea rescues, culminating in the Carpathia&#’;s Wellfleet transmitter continued in commercial use. Skilled telegraphers sent out messages at the rate of 17 words a minute, and station CC (Cape Cod) served in effect as the first “Voice of America.”

The End of an Era

The demise of the South sparkgap station was inevitable. The sea cliff was eroding three feet each year, threatening the eastern-most towers with collapse. The station was closed in 1917 by the Navy to ensure security and news censorship during World War I. New inventions were making spark-gap transmission obsolete. The station was never reopened and in 1920 it was scrapped. The barn-red towers were dismantled, useful equipment was salvaged, and the buildings, once filled with the excitement and sounds of communication, were abandoned. Old CC was replaced by Wellfleet in Chatham, and it served as the most heavily used ship-to-shore radio station on the East Coast until its closure in 1993.

A Changed World

The early 20th century was an era of new achievements and new horizons. Wireless communication affected the world in many ways. It heightened interest in events beyond the bounds of daily contact. It affected national unity. It raised new possibilities of what could be accomplished. It brought new efficiency to business — and to warfare. WCC spent his life researching communications electronics, and his work yielded many improvements in wireless. Most significant, however, was the foundation he created for developments in radio, radar, microwaves and cellular communication. Upon his death, all wireless around the world was temporarily silenced in his honor. No one had ever received such recognition, and no one has received it since.

A Century Later

In the early 21st century we look back at a remarkable sequence of events. Communications have evolved from the speed of horse and rail to the speed of light and electricity. Most of the former South Marconi site is gone now, eroded by the relentless pounding of the Atlantic Ocean. The surrounding area is preserved as part of Cape Cod National Seashore. Though few reminders of the site remain, one can still stand on an Atlantic cliff on a winter day in South Wellfleet, Massachusetts and reflect on the event that sparked the birth of global wireless communication.