Last updated: August 6, 2022

Place

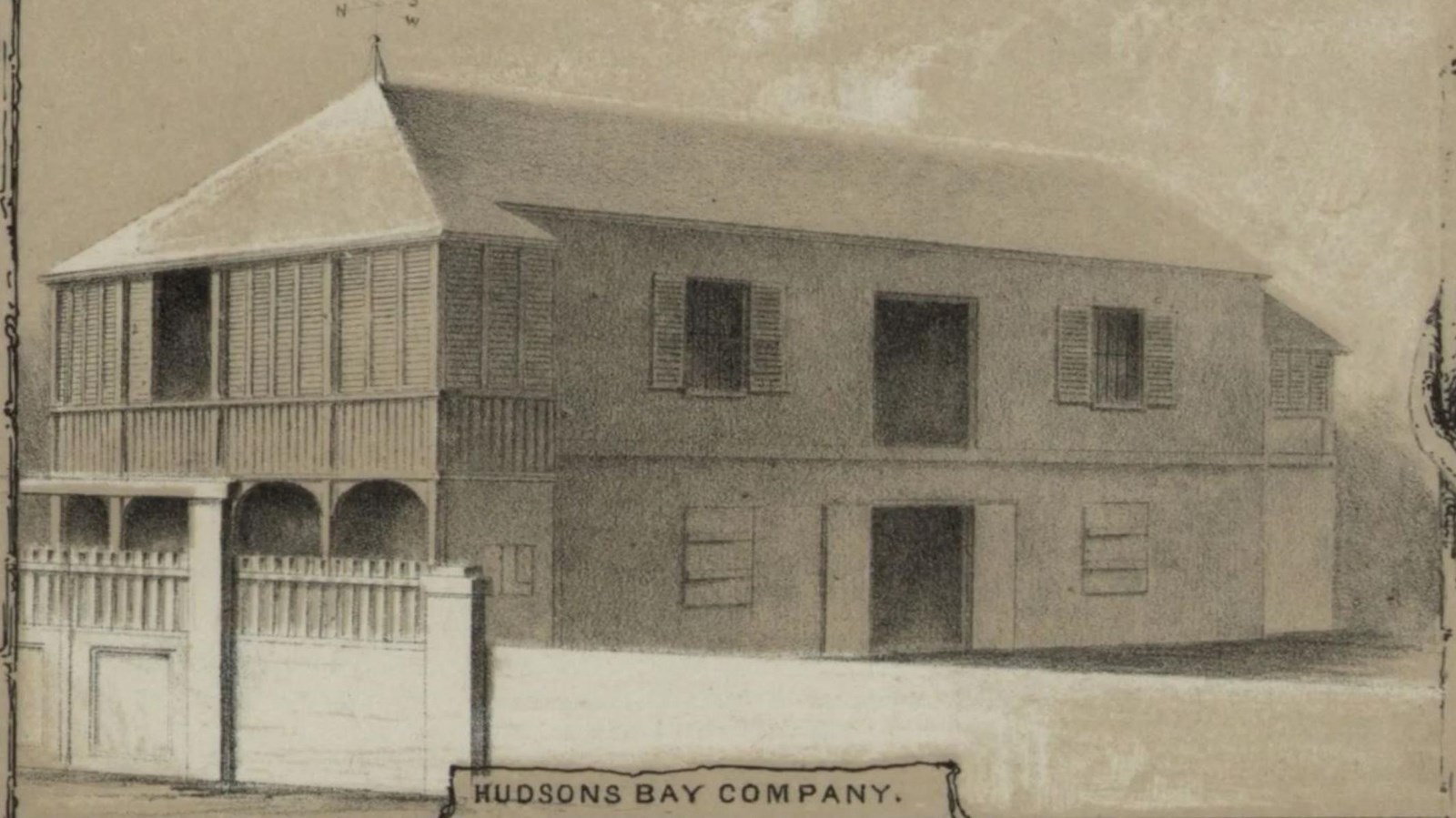

Hudson's Bay Company's Honolulu Agency

Quick Facts

Location:

Honolulu, Hawaii

The Hudson’s Bay Company's (HBC) established their Honolulu agency offices in 1829. Hawaiians had been working in the Pacific Northwest since 1787 and over time became an increasingly pivotal part of the fur trading workforce. At this office, the HBC recruited Hawaiian workers, sold British goods and Pacific Northwest agricultural products, and resupplied its ships headed from Hawaii to China and American whaling ships which regularly stopped in Honolulu. By the mid 19th Century, the Honolulu Agency was a vital part of a global trading empire that encompassed London, North America, and Asia.

Hawaiians’ importance to the HBC can be seen in the writings of Chief Factor John McLoughlin who in 1830 asked the Honolulu agency to “Sen[d] us as many of them [Hawaiians[ as possible.” These workers filled numerous vital positions for the HBC; many worked on its ships as sailors. Others, like the sixteen Hawaiians who landed on San Juan Island in 1853, were agricultural workers who grew crops and herded sheep. Still others served as construction workers whose labor helped establish fur trade outposts or as teamsters, carrying goods hundreds and sometimes thousands of miles to trade with Native Americans in the extensive network of fur trade forts that the HBC operated throughout the Pacific Northwest. It is estimated that by the mid-1800s, approximately 1/3 of the HBC’s Pacific Northwest labor force were Hawaiians.

Hawaiians were hired on time-limited contracts that specified their pay and term of service. In 1844, a Honolulu newspaper claimed that “they are generally engaged for a period of three years and gain $10 per month.” Though little documentation exists, it is likely that many of these migrant workers sent wages home to their families in Hawaii. Many Hawaiians regularly renewed their labor contracts and worked for decades in the Pacific Northwest either with the HBC or as independent settlers who homesteaded after leaving HBC employment. Hawaiian migrants also worked at other National Park Service sites that were once HBC establishments, such as Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Fort Vancouver National Historical Site, and Whitman Mission National Historic Site. On San Juan Island place names like Kanaka Bay and Friday Harbor (named after a Hawaiian man who settled there whose English name was Peter Friday) and Eastern Oregon place names like Kanaka Creek, Kanaka Bar, Kanaka Glen, and the Owyhee River demonstrate the longstanding impact of Hawaiians in the Pacific Northwest.

Hawaiians’ importance to the HBC can be seen in the writings of Chief Factor John McLoughlin who in 1830 asked the Honolulu agency to “Sen[d] us as many of them [Hawaiians[ as possible.” These workers filled numerous vital positions for the HBC; many worked on its ships as sailors. Others, like the sixteen Hawaiians who landed on San Juan Island in 1853, were agricultural workers who grew crops and herded sheep. Still others served as construction workers whose labor helped establish fur trade outposts or as teamsters, carrying goods hundreds and sometimes thousands of miles to trade with Native Americans in the extensive network of fur trade forts that the HBC operated throughout the Pacific Northwest. It is estimated that by the mid-1800s, approximately 1/3 of the HBC’s Pacific Northwest labor force were Hawaiians.

Hawaiians were hired on time-limited contracts that specified their pay and term of service. In 1844, a Honolulu newspaper claimed that “they are generally engaged for a period of three years and gain $10 per month.” Though little documentation exists, it is likely that many of these migrant workers sent wages home to their families in Hawaii. Many Hawaiians regularly renewed their labor contracts and worked for decades in the Pacific Northwest either with the HBC or as independent settlers who homesteaded after leaving HBC employment. Hawaiian migrants also worked at other National Park Service sites that were once HBC establishments, such as Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Fort Vancouver National Historical Site, and Whitman Mission National Historic Site. On San Juan Island place names like Kanaka Bay and Friday Harbor (named after a Hawaiian man who settled there whose English name was Peter Friday) and Eastern Oregon place names like Kanaka Creek, Kanaka Bar, Kanaka Glen, and the Owyhee River demonstrate the longstanding impact of Hawaiians in the Pacific Northwest.