Last updated: December 5, 2023

Place

Decision Point, Montana

Library of Congress

Benches/Seating, Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Parking - Auto, Scenic View/Photo Spot, Trailhead

Picture this: you’re traveling up a river. It’s one long, winding stream of water, and your boat makes its way through thickets of willows, shrubs, and bushes. You see beaver swimming in the stream. You occasionally stop to talk with people living in communities along side of the river.

Then you come to a point where the river diverges and becomes two streams. A few hundred miles later, one of those streams splits yet again. That third stream seems small, not the main stream of the river. But the other two are sizable—which is the way to go?

This is what the Lewis and Clark Expedition faced when they reached the confluence of the Missouri and Marias Rivers—the place later called “Decision Point.”

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wanted to end up where Shoshone people lived. Lewis and Clark knew from their Mandan and Hidatsa hosts that Shoshone people knew an overland route across the Rocky Mountains. Lewis and Clark hoped that Shoshone people might be willing to sell them horses and guide them across the route.

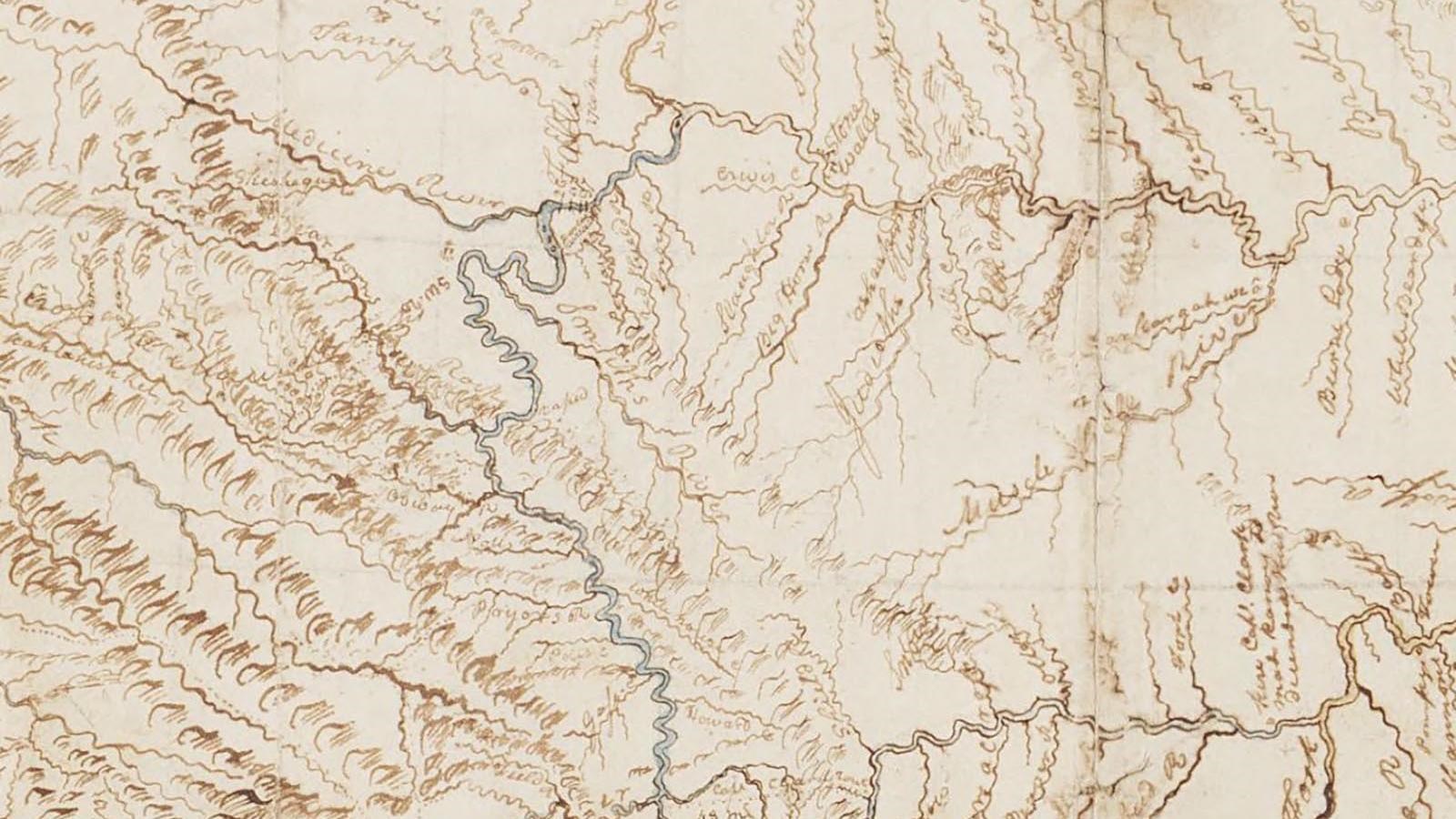

Lewis had survey instruments and a British-made map, which the author had drawn from knowledge he learned from Blackfeet people. Several men in the Lewis and Clark Expedition had spent their lives on river boats and knew how water behaved. They could try to determine which stream was easier to boat on, or which stream went farther up the mountains. And Sacagawea had been here before and knew this river.

Lewis led a party up one stream, and Clark led a party up the other. Did the clear waters of the stream on the left indicate that it came from the mountains? Or did the muddy waters of the stream on the right that resembled those they had been traveling on mean that it was the way to go?

Members of the expedition disagreed on which was the correct fork. Although most believed the right-hand fork was the more significant stream, the group ultimately decided to trust what Mandan and Hidatsa people and Sacagawea had told them, and they took the stream on their left-hand side.

With the decision made, everyone celebrated: Pierre Cruzatte played the fiddle and the captains doled out some grog.

About this article: This article is part of a series called “Pivotal Places: Stories from the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.”

Lewis and Clark NHT Visitor Centers and Museums

This map shows a range of features associated with the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which commemorates the 1803-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition. The trail spans a large portion of the North American continent, from the Ohio River in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon and Washington. The trail is comprised of the historic route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, an auto tour route, high potential historic sites (shown in black), visitor centers (shown in orange), and pivotal places (shown in green). These features can be selected on the map to reveal additional information. Also shown is a base map displaying state boundaries, cities, rivers, and highways. The map conveys how a significant area of the North American continent was traversed by the Lewis and Clark Expedition and indicates the many places where visitors can learn about their journey and experience the landscape through which they traveled.