Last updated: October 10, 2024

Place

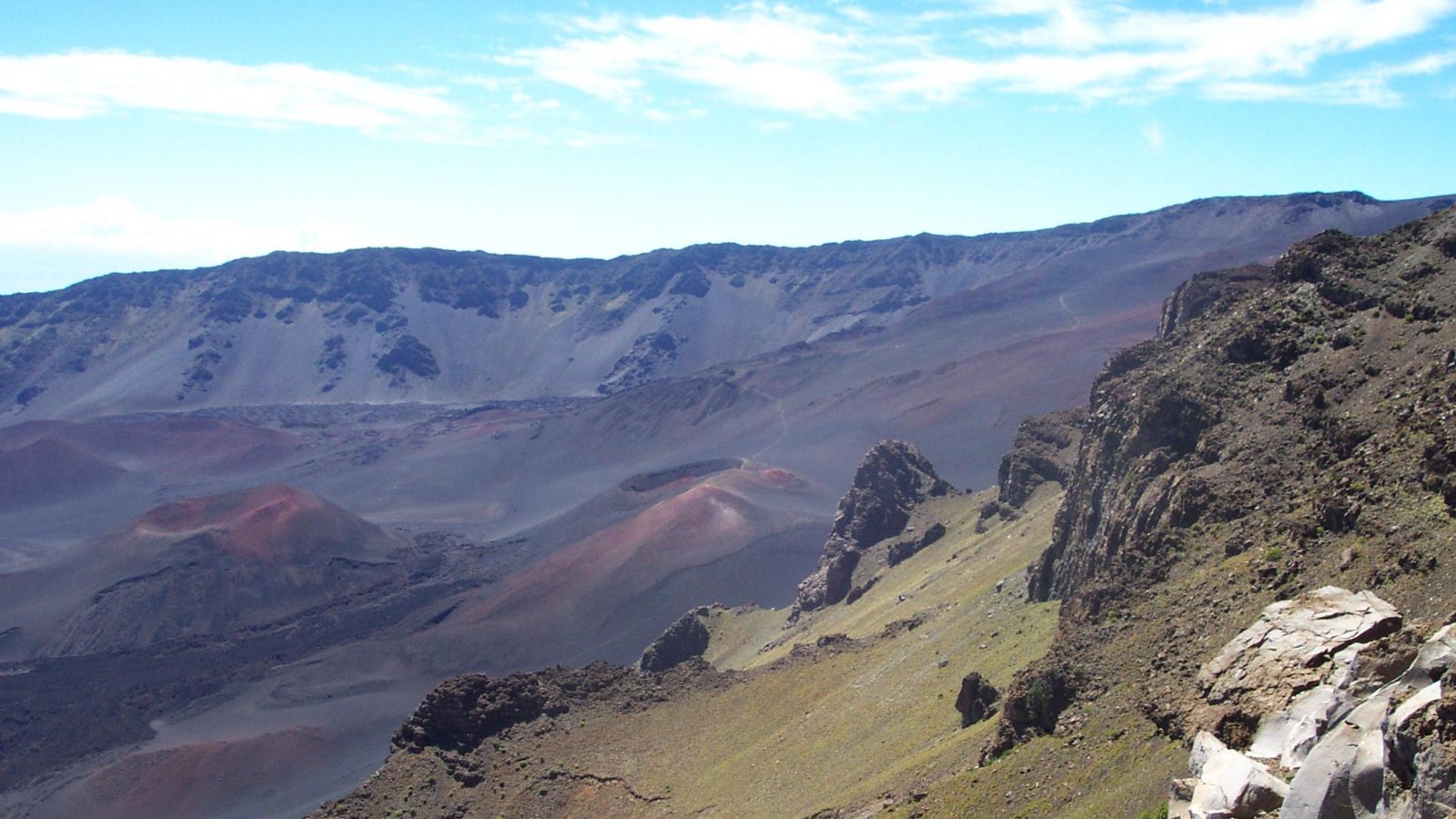

Crater View at Kalahaku

NPS Photo

Quick Facts

Location:

Summit District

Significance:

Stop 6 on the Geology Road Tour

Amenities

2 listed

Scenic View/Photo Spot, Toilet - Vault/Composting

It took two million years for this landscape to take shape, molded by the countless layers of lava beneath, the relentless heat of the mantle plume below Hawai‘i, and the slow erosion of rain against the mountainside. Through the windows of the shelter, you can reflect on a storied landscape carved by creation and destruction – eruption and erosion.

How many eruption features can you see “crater” valley floor? What about erosion features? On a clear day, there are 13 puʻu visible on the valley floor. They may look small, but some are nearly 1,000 feet tall! These cone-shaped eruption features formed during the eruption of “fire fountains.” When very runny and extremely hot basaltic material gets pushed out of a fissure in the volcano by gas pressure, jets of that molten lava can shoot thousands of feet up in the air. That projectile lava cools as it falls to the ground, piling up around the base of the fire fountain and welding together into the cinder or scoria cones you see today. Fire fountains look very dramatic but are only mildly explosive.

These eruption events are part of the process of creating new land. The longer a Hawaiian volcano remains near a heat source, the more rock it spills out, and the larger the island becomes. This volcano is moving away from its heat source – not a convergent tectonic plate boundary like what fuels the volcanoes along the “Ring of Fire”, or a divergent plate boundary like what fuels volcanism in the East African Rift. Instead, this volcano’s activity is driven by a hotspot or mantle plume, a current of heat rising from a deeper layer of the planet which melts the crust above in just one area at a time. There are dozens of mantle plumes on the planet, but some are more famous than others – Yellowstone, Galapagos, and Iceland (also on a divergent plate boundary) are a few examples.

As the moving Pacific Plate slowly drags Maui westward, away from the mantle plume that’s now centered underneath Hawai‘i Island, the eruptions from this volcano have become less productive, and the forces of weathering and erosion now dominate the landscape. The deep valleys leading to the ocean, tall pali (cliffs) towering on each side of the crater, and the roaring waterfalls of the Kīpahulu District are the signifiers of this erosion.

How many eruption features can you see “crater” valley floor? What about erosion features? On a clear day, there are 13 puʻu visible on the valley floor. They may look small, but some are nearly 1,000 feet tall! These cone-shaped eruption features formed during the eruption of “fire fountains.” When very runny and extremely hot basaltic material gets pushed out of a fissure in the volcano by gas pressure, jets of that molten lava can shoot thousands of feet up in the air. That projectile lava cools as it falls to the ground, piling up around the base of the fire fountain and welding together into the cinder or scoria cones you see today. Fire fountains look very dramatic but are only mildly explosive.

These eruption events are part of the process of creating new land. The longer a Hawaiian volcano remains near a heat source, the more rock it spills out, and the larger the island becomes. This volcano is moving away from its heat source – not a convergent tectonic plate boundary like what fuels the volcanoes along the “Ring of Fire”, or a divergent plate boundary like what fuels volcanism in the East African Rift. Instead, this volcano’s activity is driven by a hotspot or mantle plume, a current of heat rising from a deeper layer of the planet which melts the crust above in just one area at a time. There are dozens of mantle plumes on the planet, but some are more famous than others – Yellowstone, Galapagos, and Iceland (also on a divergent plate boundary) are a few examples.

As the moving Pacific Plate slowly drags Maui westward, away from the mantle plume that’s now centered underneath Hawai‘i Island, the eruptions from this volcano have become less productive, and the forces of weathering and erosion now dominate the landscape. The deep valleys leading to the ocean, tall pali (cliffs) towering on each side of the crater, and the roaring waterfalls of the Kīpahulu District are the signifiers of this erosion.