Last updated: August 14, 2023

Place

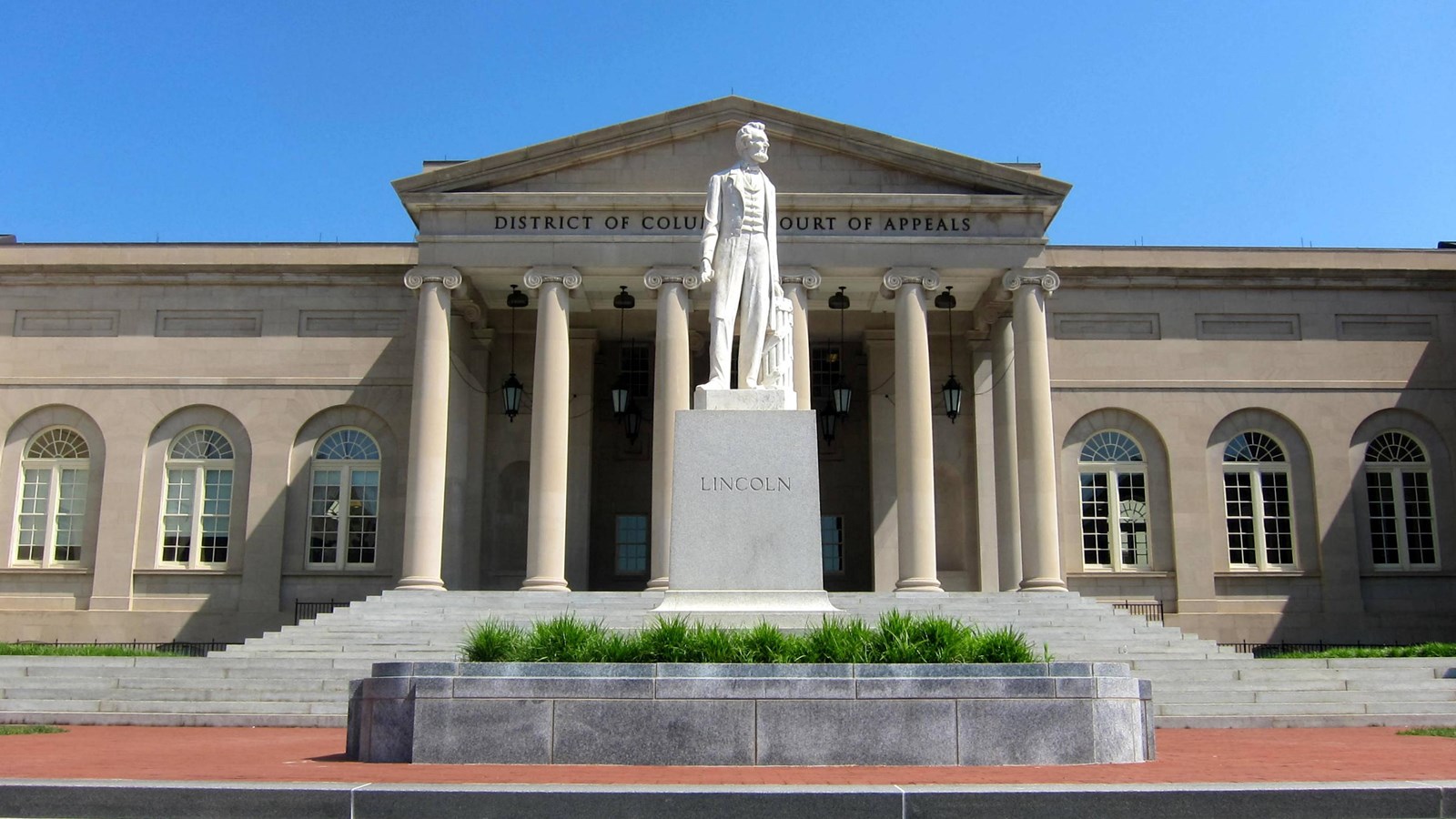

City Hall/District of Columbia Courthouse

By AgnosticPreachersKid, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10501078

Mismanagement and insufficient funding from the local government delayed the completion of the District of Columbia City Hall/Courthouse for over thirty years. The original stucco-covered brick structure was finally completed in 1849.

Over the decades-long construction period, tenants leased parts of the building to provide funding. These tenants included the U.S. Circuit Court and Recorder of Deeds office. Before the Civil War, the trials of abolitionists and Underground Railroad conductors charged with aiding freedom seekers were held here. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 mandated the capture and return of self-liberated people, even in the free states, and imposed harsh penalties for those who helped people avoid capture.

In 1863, the federal government formally purchased the City Hall/Courthouse to house the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. Major renovations occurred between 1916 and 1918. Only 25% of the original structure was retained. Renovators completely redid the interior and reconstructed the exterior in stone. The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

On April 14, 1871, Mary Ann attempted to register to vote in Washington, D.C.’s second delegate district. She went before a seven-member Board of Registration in the City Hall/Courthouse building to provide proof of residency. Mary Ann knew two African American members of the Board, John F. Cook and John S. Crocker. Despite their acquaintance, the Board turned Mary Ann's registration down. She documented the events before a notary five days later. She claimed the Board wrongfully denied her legal right to vote “pursuant to the act of Congress.” This likely referred to the Fifteenth Amendment. Ratified in 1870, this Amendment stated that voting rights could not be denied based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Mary Ann criticized the Fifteenth Amendment because it did not extend voting rights for African American women.

Two years later, Mary Ann joined 599 other citizens who signed a petition advocating for women’s legal voting rights. She passed away from stomach cancer in 1893, almost thirty years before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. The Amendment prohibited the obstruction of voting rights on the basis of sex. Even after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, many African American women were denied access to the ballot by violence, poll taxes, literacy tests, and other means. These barriers were outlawed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Bibliography:

Cary, Mary Ann Shadd. Oath of Residence. April 19, 1871. Certificates and Statements, Folder 6. Mary Ann Shadd Cary Collection. Digital Howard @ Howard University, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C. Accessed June 5, 2020, https://dh.howard.edu/mscary_certs/6.

DC Historic Sites. “Old City Hall (District of Columbia Court of Appeals.)” Sites. Access June 5, 2020. https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/437.

Rhodes, Jane. Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Washington, DC NHL City Hall/DC Courthouse; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: Washington, D.C; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013-2017; Records of the National Park Service, 1785-2006, Record Group 79; Washington, D.C. Accessed June 4, 2020. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/117691801.