Last updated: April 4, 2021

Place

Preserving the Past (Arch Point Tour)

Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Stop 2: Arch Point Tour

An island ranch is a study in self-reliance. With no stores, phones...everything has to be fashioned from whatever is on hand; it's the art of making do.

-Gretel Ehrlich, Cowboy Island: Farewell to a Ranching Legacy

While the isolated island offered ranchers several advantages over the mainland, including no predators and the world's best fence (the ocean), it created special challenges as well. Supplying such a remote outpost was probably the most considerable of these. The transportation of supplies and stock on and off the island was always an adventure-the distance to the mainland, rough seas, and high expense made it very difficult. However, ranchers adapted to the challenges of island life through self-reliance and, as one ranch foreman wrote, "learning to make do with what [they] had."

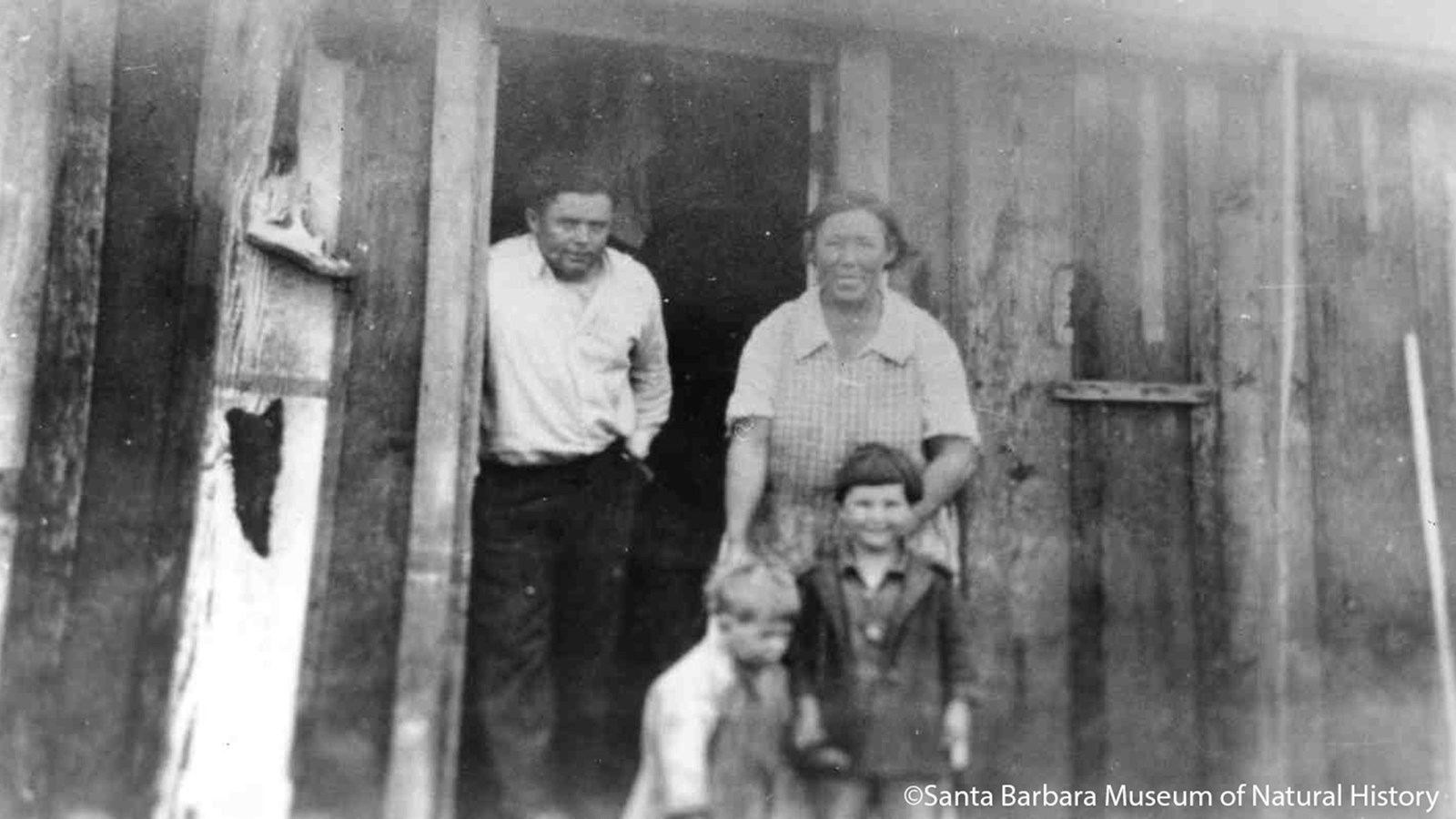

No one was better suited to this island life than Alvin Hyder, who lived on Santa Barbara Island along with his extended family from 1914 to 1922. According to Alvin's son, Buster, "The ol' man got up with a lantern and went to bed with a lantern. Eight hours was just getting' started. He worked all the time. He was a hard-working man who never knew when to stop."

In order to produce income and be as self-sufficient as possible, the Hyders developed a diverse operation: they raised various crops (barley, corn, and potatoes), maintained a vegetable garden, and imported different animals, including sheep from Santa Cruz Island, horses, mules, pigs, goats, rabbits, chickens, ducks, geese and turkeys.

Not all of these enterprises succeeded. "Too much guano in the ground...burned [the potatoes]." High winds wreaked havoc on the chickens and geese: "We watched more gosh darn chickens and turkeys and our stuff blow out in that ocean--blow 'em clear out." One terrible year, the Hyders even lost their entire hay harvest: "We sold our hay to this guy [in San Pedro], and he went bankrupt. We lost all of our feed and all our work...we got skunked."

Raising sheep for wool and meat eventually became the mainstay of the Hyder operations. But even this had its challenges. One of the biggest was transporting the sheep and supplies to the top of the island. To accomplish this difficult task, the Hyders constructed a wooden track with a sled that ran between the Landing Cove and the house. A horse pulled the sled up the track, and people lowered it by hand. The horse, named Dan, listened for a signal from below to start hauling, and stopped when the load was exactly at the barn.

To supplement the family income, Alvin ran rum during Prohibition along the Southern California coast and transported animals and supplies to and from other islands aboard his boat, Nora. The family also fished and collected sea gull eggs which were boiled because they were so oily. Occasionally, hunger and lack of supplies would drive family members to eating mice and brushing their teeth with green coreopsis branches, a practice Buster describes: "When [the coreopsis] were green I used to break them off and scrub my teeth with them. No kiddin'. We had no toothbrushes...and no toothpaste. So I used to clean my teeth with the things. It's just like eatin' an apple, and it keeps your teeth slick and clean. Maybe that's why I got all my teeth still."

The lack of fresh water also posed a challenge. Since the island had no springs or flowing water, the Hyders constructed a system of reservoirs. They built two large concrete cisterns at the house and brought water from the mainland on Nora II in twenty-five 50-gallon barrels. This water was then pumped to the house reservoir. They also collected water from the building roofs and constructed two water catchment basins on the island for the livestock and crops. To ensure water quality, Buster had the job of removing dead mice from the drinking water supply every day.

Despite these actions, water remained a precious resource as Buster recalled, "You had to limit your drinking water. It had to last a year. Then it got stagnant. Many times when it was raining I'd drink water out of horse tracks. No kiddin'. Boy, it was hard to drink it. But when you don't have anything else, you have to drink it."

Besides the lack of fresh water, the Hyders also lacked natural resources for construction materials. With no trees on the island, all supplies for facilities had to be brought from the mainland. The Hyders built a two-room wooden ranch house above the Landing Cove for the families of both Alvin and his brother, Clarence, to share. A barn, stable, and a chicken coop were located nearby. Alvin's other brother, Cleve, and his wife built their own small house half way up from the Landing Cove. At one time around 1915 some 15 people lived on this little island.

With all of these difficulties and setbacks, it may come as no surprise that the Hyders finally decided to leave the island in 1922, after years of hard work and frustration. They tore down the buildings for lumber and removed their animals with the exception of the rabbits and a mule. The Hyders were the only family to permanently reside on this isolated island.

After the Hyders, only government activity occurred on the island. From 1942 through 1946, the island served as a military coastal lookout station, which consisted of a lookout tower, radio antenna, roads, boat landing with tramway, and barracks. A staff of seven men on 24-hour duty kept a lookout for all passing vessels and submarines. Two unmanned navigational light towers were also constructed, one of which is still operational and can be seen near Arch Point.

As you might expect, military life was a little different on an isolated island. Cal Reynolds remembered his 1942 duty time at the station as "very hang loose . . . not a lot of regimentation, we stood our four on and eight off . . . it was a small island, there wasn't a lot to do on it." The men worked two weeks on the island and then received one week of leave. They kept chickens and rabbits in pens, and fished and tended lobster pots: "[we] always had hot buttered lobster." Even though the Navy had constructed a water storage tank and pumped water up from the dock, water was still scarce and the men were unable to keep a garden. A weekly boat brought supplies and transferred men on and off the island. "It was a good life," Reynolds recalled, "an enjoyable experience."

Even today, the isolation of this island still affects visitors and the National Park Service. Public boat trips for park visitors are limited to only a few days each month during the summer and visitors must bring (and carry up to the top of the island) all their own food and water. Park staff must import food and water as well, and have established a solar power system for energy. Like so many who visited and resided here before, we must learn to make do with what we have.

Visit the Hyder Ranch site pin for more information.