Last updated: May 21, 2024

Place

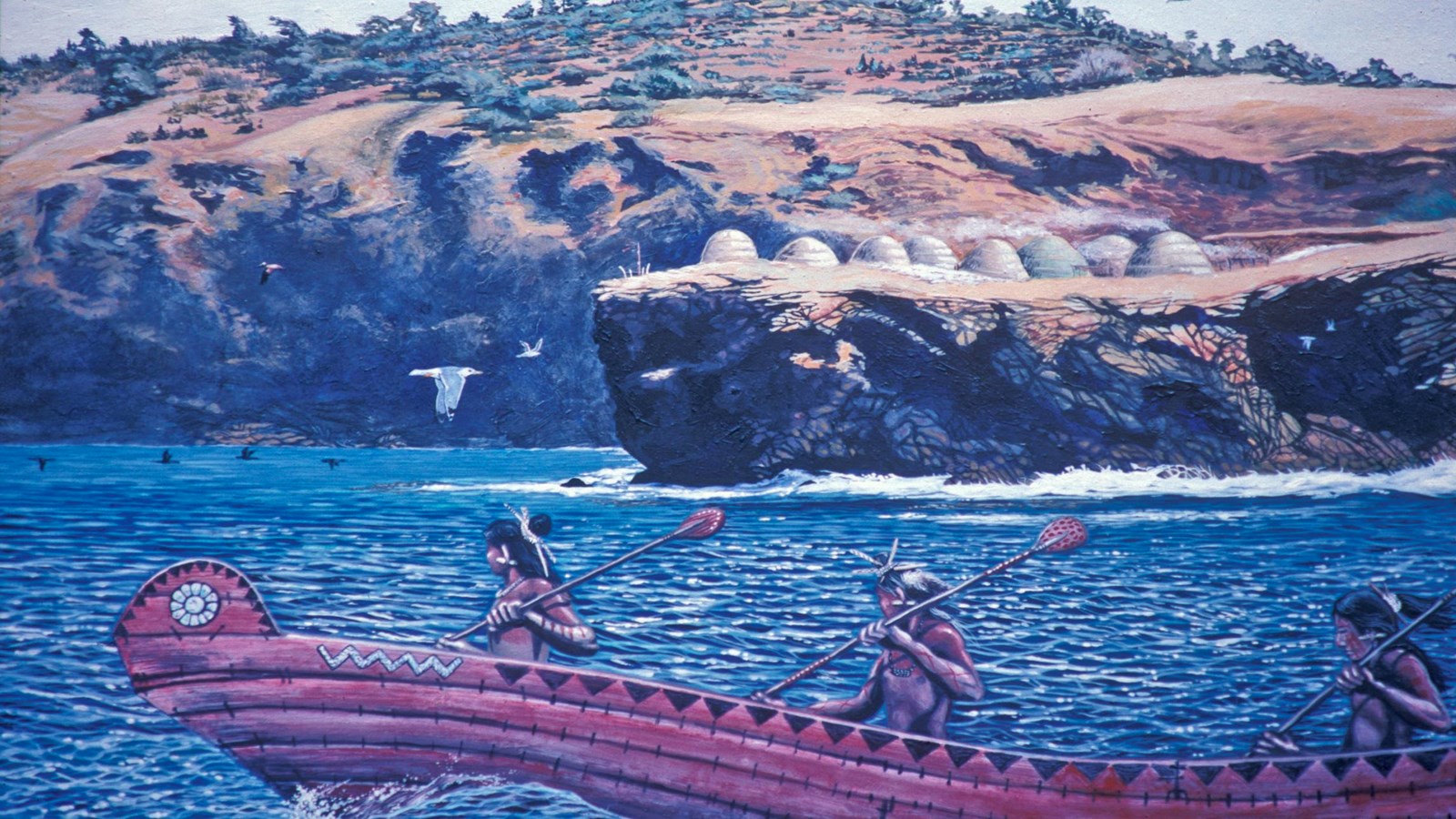

hichimin Chumash Village

Michael Ward

The second largest historic Chumash village on Santa Rosa Island, hichimin (or hitšǝwǝn), was located within Becher's Bay. Current research and radiocarbon dating suggests that this site was first occupied 650 years ago. At the time of European contact (Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo's voyage in 1542) the village was home to approximately 75 Chumash, including many high-ranking families, a powerful chief, and tomol (plank canoe) owners.

Although Chumash occupation of Santa Rosa Island ended in the early 19th century, many individuals today can trace their ancestry to specific villages on the island and retain a lively interest in the preservation and management of their heritage. Between three and ten thousand Chumash live in California today.

Taking from or disturbing archeological sites or artifacts is a violation of state and federal law. The archeological sites around the Channel Islands are a testament to the importance of the Chumash and other American Indians. Archeological sites are sacred to Chumash peoples today, are protected by federal law, and are a vital nonrenewable scientific resource. Please help us in protecting and preserving this rich part of California's heritage.

More Chumash History

Chumash on Santa Rosa Island

Archaeologist Phil Orr's discovery of human bones in 1959 at Arlington Springs provided evidence of the oldest known habitation of the island. Recently radio-carbon dated to 13,000 years before present, these are among the oldest securely-dated human remains in North America. The age of the Arlington remains and a host of archeological sites on the Channel Islands that date to the late Holocene (10,000-6,500 years before present) indicate an early migration route from the Old World into North America along the West Coast.

Santa Rosa Island and the other Channel Islands provided rich resources for seafaring peoples to thrive by hunting seabirds, sea mammals, fish and shellfish. With extensive trade networks on the mainland, the island Chumash were able to trade marine resources with mainland peoples for goods they could not harvest or produce on the island. With plentiful food and fresh water, the island supported several villages at the time of European contact.

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed up the coast of California in 1542, the first European to visit the Channel Islands, and documented three villages on Santa Rosa Island. A half-century later, Sebastian Rodriguez Cermeño wrote about his interaction with the Chumash on the south side of the island on December 13, 1595, as he sailed southward along the coast: "...and there came alongside a small boat like a canoe, with two Indians in it rowing. And having arrived at the launch, they brought some eighteen fish and a seal and gave them to us, for which we gave them some pieces of taffeta and cotton cloth in order that they should bring more. They went on shore and returned in the same boat with three Indians and brought nothing, At this island we went fishing with lines and caught some thirty fishlike cabrillas sea bass], which we soon ate on account of our great hunger....On both [Santa Rosa Island and Santa Cruz Island] the land is bare and sterile, although inhabited by Indians, there are no ports or coves in them in which to take shelter."

Chumash on the Channel Islands

Archeological evidence indicates that there has been a human presence in the northern Channel Islands for thousands of years. Human remains excavated by archeologist Phil Orr from Arlington Springs on Santa Rosa Island in 1959, recently yielded a radio-carbon date of over 13,000 years of age. Archeological sites on San Miguel Island show continuous occupation from 8,000 - 11,000 years ago.

The native populations of the Channel Islands were primarily Chumash. The word Michumash , from which the name Chumash is derived, means "makers of shell bead money" and is the term mainland Chumash used to refer to those inhabiting the islands. Traditionally the Chumash people lived in an area extending from San Luis Obispo to Malibu, including the four Northern Channel Islands. Today, with the exception of the Islands, Chumash people live in these territories and areas far beyond. Approximately 148 historic village sites have been identified, including 11 on Santa Cruz Island, eight on Santa Rosa Island, and two on San Miguel Island. Due to the lack of a consistent water source, Anacapa Island was likely inhabited on a seasonal basis. A true maritime culture, the Chumash hunted and gathered natural resources from both the ocean and the coastal mountains to maintain a highly developed way of life.

The southernmost park island, Santa Barbara Island, was associated with the Tongva people, also called Gabrieleno, although the Chumash also visited the island. Like the Chumash, they navigated the ocean and traded with their neighbors on the northern islands and the coast. Lacking a steady supply of fresh water, no permanent settlements were ever established on Santa Barbara Island. Tongva/Gabrieleno people lived primarily on the Southern Channel Islands (Santa Barbara, San Nicolas, Santa Catalina and San Clemente islands) and the area in and around Los Angeles.

Navigation, Trade, and the Tomol

These earliest inhabitants exploited the rich marine resources. Isolated from the mainland, they navigated between the islands and back and forth to the mainland using tomols . A plank canoe constructed from redwood logs that floated down the coast and held together by yop , a glue-like substance made from pine pitch and asphaltum, and cords made of plant materials and animal sinews, the tomol ranged from eight to thirty feet in length and held three to ten people. Sharkskin was used for sanding, red ochre for staining, and abalone for inlay and embellishment.

The use of the tomol allowed for an elaborate trade network between the islands and mainland, between natives and non-natives, and amongst the island communities themselves. 'Achum , or shell bead money was "minted" by the island Chumash using small discs shaped from olivella shells and drills manufactured from Santa Cruz Island chert. The shell bead money was exchanged with mainland villages for resources and manufactured goods that were otherwise unavailable on the islands.

Today, the Chumash Maritime Association, in partnership with Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary and Channel Islands National Park, continues the tradition of the tomol by conducting Channel crossings.

Missionization

By the time European explorers arrived in the Santa Barbara Channel, there were some 21 villages on the three largest islands of San Miguel, Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz, with highly developed social hierarchies that featured an upper class of chiefs, shamans, boat builders, and artisans, a middle class of workers, fisherman, and hunters, and a lower class of the poor and outcast. Because of the scarcity of fresh water, Anacapa and Santa Barbara islands did not support permanent habitation.

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo was impressed by the friendliness of the Chumash people he encountered. However, diseases introduced by the European explorers began a decline in the native population. As European colonists began to settle along the coast, introducing new economic enterprises, exploiting the marine resources, and establishing Catholic missions, the native food sources were depleted, native economies were altered, and island populations declined even further. By the 1820s, the last of the island Chumash had moved to the mainland, many of them to the Missions at Santa Ynez, San Buenaventura, and Santa Barbara.

The mission system depended on the use of native labor to propel industry and the economy. The social organization of Chumash society was restructured, leading to the erosion of previous power bases and further assimilation. When California became part of Mexico, the government secularized the missions, and the Chumash sank into the depths of poverty. By the time of the California gold rush, the Chumash had become marginalized, and little was done to understand or help the remaining population.

Contemporary Chumash

Today, Chumash community members continue to move forward in their efforts to revive what was becoming a forgotten way of life. Much has been lost, but Chumash community members take pride in their heritage and culture.

With a current population nearly 5,000 strong, some Chumash people can trace their ancestors to the five islands of Channel Islands National Park. The Chumash reservation in Santa Ynez represents the only federally recognized band, though it is important to note that several other organized Chumash groups exist.

The National Park Service invites you to visit Channel Islands National Park, Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, and other local areas to learn more about the Chumash and other Native American cultures.

More information about Chumash history and culture can be found at the following links:

- Chumash Indian Life at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

- Santa Ynez Chumash History

Limuw: A Story of Place

Hutash , the Earth Mother, created the first Chumash people on the island of Limuw, now known as Santa Cruz Island. They were made from the seeds of a Magic Plant.

Hutash was married to the Alchupo'osh , Sky Snake, the Milky Way, who could make lightning bolts with his tongue. One day he decided to make a gift to the Chumash people. He sent down a bolt of lightning that started a fire. After this, people kept fires burning so that they could keep warm and cook their food.

In those days, the Condor was a white bird. The Condor was very curious about the fire he saw burning in the Chumash village. He wanted to find out what it was. He flew very low over the fire to get a better look, but he flew too close; he got his feathers scorched, and they turned black. Now the Condor is a black bird, with just a little white left under the wings where they did not get burned.

After Alchupo'osh gave them fire, the Chumash people lived more comfortably. More people were born each year and their villages got bigger and bigger. Limuw was getting crowded. And the noise people made was starting to annoy Hutash . It kept her awake at night. So, finally, she decided that some of the Chumash people had to move off the island. They would have to go to the mainland, where there weren't any people living in those days.

But how were the people going to get across the water to the mainland? Finally, Hutash had the idea of making a bridge out of a wishtoyo (rainbow). She made a very long, very high rainbow that stretched from the tallest mountain on Limuw all the way to Tzchimoos , the tall mountain near Mishopshno (Carpinteria).

Hutash told the people to go across the rainbow bridge and to fill the whole world with people. So the Chumash people started to go across the bridge. Some of them got across safely, but some people made the mistake of looking down. It was a long way down to the water, and the fog was swirling around. They became so dizzy that some of them fell off the rainbow bridge, down through the fog, into the ocean. Hutash felt very badly about this because she told them to cross the bridge. She did not want them to drown. To save them, she turned them into dolphins. Now the Chumash call the dolphins their brothers and sisters.

Excerpted from:

The Chumash People: Materials for Teachers and Students . Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, 1991.

Contemporary Chumash Tomol Crossing

Each day, commercial and private boats take visitors across the Santa Barbara Channel to the shores of the Channel Islands. Can you imagine making that same journey in a canoe? It might take an entire day and would require tremendous physical strength to forge through the rough waters.

Hundreds of years ago, the native island Chumash traveled these ancient waters for hunting, fishing, and trading. They built canoes, called tomols , from redwood trees that drifted down the coast, fastening the cut planks together with animal sinews and sealed with a tar-like substance called yop . Yop is a combination of pine pitch and asphaltum which occurs naturally in the Channel and along the coast from oil seeping into the water from below the earth's surface. The tomol remains the oldest example of an ocean-going watercraft in North America.

The tomol is central to the Chumash heritage, constructed and paddled by members of the Brotherhood of the Tomol . The historic Brotherhood disbanded in 1834, but in 1976, a contemporary group built Helek , which means peregrine falcon, based on ethnographic and historic accounts of tomol construction. It was the first tomol built in 142 years and the modern paddlers travelled from San Miguel Island to Santa Rosa Island, and finally to Santa Cruz Island.

Twenty years later, the Chumash Maritime Association completed a 26-foot-long tomol which they named ˜Elye'wun (pronounced "El-E-ah-woon"), the Chumash word for Swordfish.

On September 8, 2001, ˜Elye'wun made the historic crossing from the mainland to Santa Cruz Island. The dangers of the past did not escape the modern crew. During the journey, the tomol began to leak and also encountered a thresher shark and several dolphins. Over 150 Chumash families and friends gathered to greet the tomol and paddlers on the beaches of Santa Cruz.

Three years later, on September 11, 2004, ˜Elye'wun again crossed the Channel to Santa Cruz Island, this time greeted by more than 200 Chumash and American Indians at the historic Chumash village of Swaxil , now known as Scorpion Valley. The 21-mile trip took over ten hours! A crew of Chumash youth aged 14 to 22 joined the paddlers, a significant accomplishment for the next generation of Chumash leaders.

Additional tomol crossings took place in September 2005 and August 2006. Members of the Chumash community continue to celebrate their heritage and culture through this event.

Centuries ago, the tomol was used to connect different island Chumash groups with each other and the mainland. Today, it links past generations of Chumash with the present-day Chumash community.

Ethnographic Island Place Names

Ethnographic island place names aid in native language revitalization, illustrate cultural values, and provide tangible connections to cultural landscapes and seascapes.

Many of these place names were recorded by ethnographers and anthropologists in the late 1800 and early 1900s. J.P. Harrington was an ethnographer who worked for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., from 1915 to 1955. He interviewed American Indian consultants, including Chumash and Gabrielino Tribal members, and recorded information about native languages and culture.

Chumash Indians Fernando Librado (Kitsepawit) and Juan Estevan Pico were the main sources for island place names. They were both born and raised in Ventura. They learned of the island places from Chumash elders, most notably Ursula (of wima) and Martina (of limuw.) Pico's interviews of Martina resulted in a list of island place names given in order from east to west (or vice/versa,) to anthropologist, H.W. Henshaw. Anthropologists have cross-referenced Pico's list with the archeological record, baptismals, and marriage patterns.

Twenty-six new place names were recently identified and mapped by Matthew Vestuto (Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians; Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival) with assistance from Kristin Hoppa (Archeologist, Channel Islands National Park) and the Chumash community. These names reference island peaks, water, landforms, islets, trails, caves, and beaches.

Please note that lowercase is used because capitalization is a convention in English which poses problems in the writing of native languages.