Last updated: March 2, 2021

Place

A Mob of Soldiers: Philippines War Tour

This letter illustrates how regional and racial tensions were running high at this time in the country, and the role that these played in the Tennessee volunteers getting their reputation.

August 15, 1898

Dear Uncle John,

You would certainly laugh were you to visit Frisco about now, and ask a citizen about that Tennessee regiment. He would tell you they are the worst men for fighting you ever saw. The New York boys run from us. We have come out ahead in every scrap so far, but when we first moved to the Presidio where we are now situated some of them made the remark they were going to throw us in the bay when they caught us out, but it is the other way now.

This morning when I got up some one says catch that negro and about four hundred men started after a negro. He had hit one of our men with a pair of brass knuckles and run you might say for his life, for I tell you, the boys who chased him tried to kill him, some one struck him in the head with a rock while others trying to cut him with knives, but Major Cheatham came in time with the guards to keep off the crowd, but if he had been five minutes later the negro would have been cut all to pieces. It looks like this regiment has to have somebody to fight any way, but we still have some hope of going to Manila.

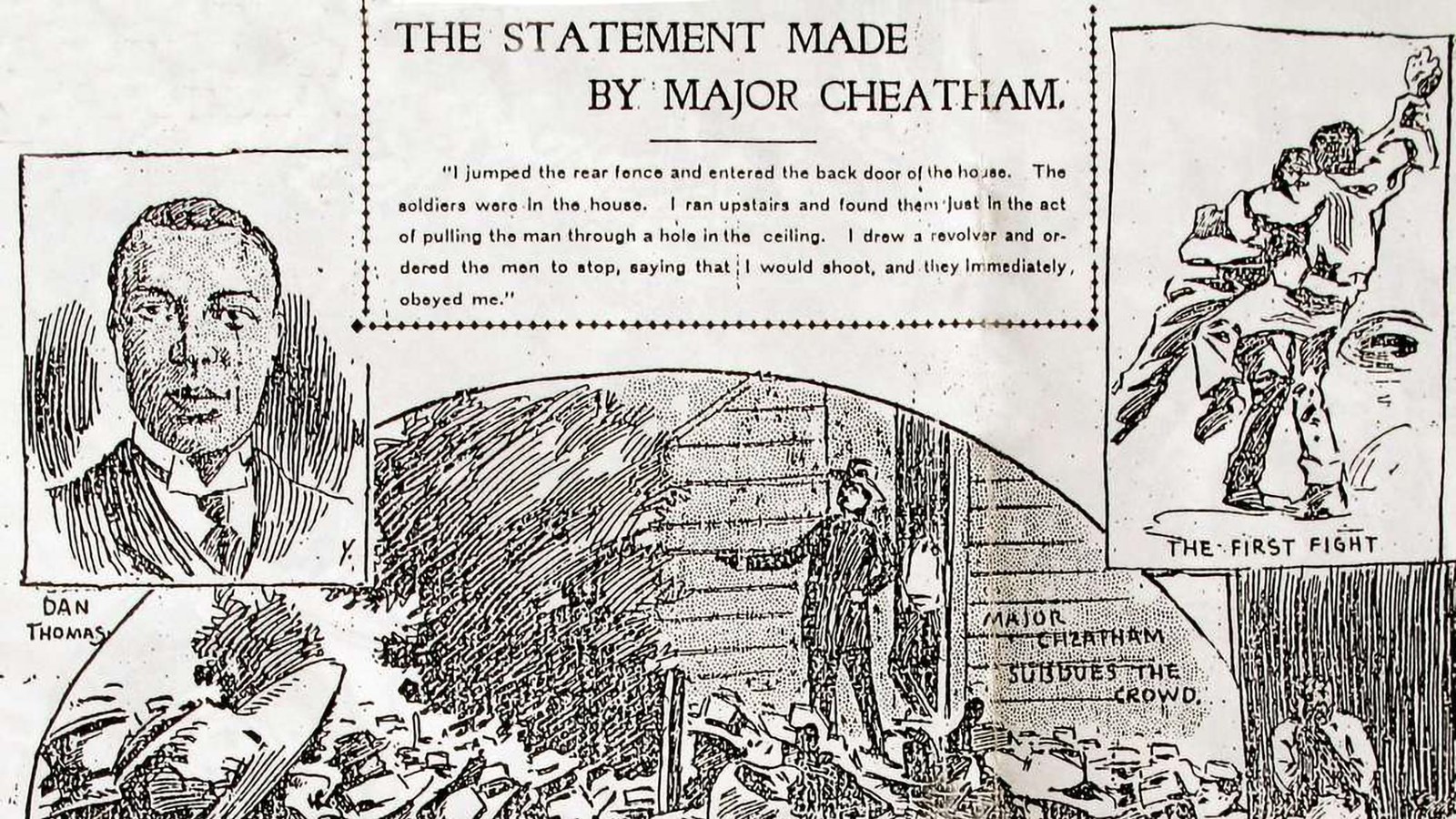

The near-lynching of the African American by the Tennessee regiment warranted a full page spread in the San Francisco Call newspaper on August 16, 1898,

Soldiers of Tennessee Mob a Negro, Drunken Row Almost Results in a Murder

The trouble began on Baker Street, between Filbert and Greenwich. The victim Dan Thomas reported:

"I was on my way back from Dwyer's saloon, on the corner of Filbert and Baker streets, where I had been delivering some crabs, when two soldiers stopped me. One of them asked for a chew of tobacco and the other for a dime. I told them I had no tobacco and no dime, and then one of them hit me. I hit back and then I ran home as fast as I could, a lot of soldiers following me. I told my brother and mother they were after me to kill me, and then I climbed up into the garret. I heard them come into the house, and I stayed where I was until an officer told me it was safe to come down."

Major Cheatham of the Tennessee Volunteers, who took a prominent part in the rescue, and who undoubtedly saved Thomas from death, said:

"I was sitting in the mess tent this morning about 7:30 when I saw a number of men running down the road from our camp. I asked one of our men what the trouble was, and he said that one of our regiment had been killed by a negro and that the crowd was after him. I quickened my pace toward the entrance to the reservation, and just as I arrived I saw a large crowd running down the hill. I ran to the house where the men were gathered. I jumped the fence and entered the back door and ran up the stairs. There I found soldiers pulling a man through a hole in the ceiling. I drew a revolver and ordered the men to stop, saying that I would shoot, and they immediately obeyed me. I took the negro in charge, appointed guards over him, taking the very two men who were closest upon him for this purpose, and we brought him back to camp."

General Miller's indignation at the barbarous treatment of the negro knew no bounds. The general said:

"The negro did not use brass knuckles on the soldier, but he did very good service with his fist-just about what the soldier deserved: and the whole company, or what amounted to a company in numbers of Tennesseans and Iowans who attacked him afterwards. I had him placed in the post guardhouse, and if any attempt had been made to take him back, as I hear was contemplated, the perpetrators would have met with a warm reception from the Washington guard. A soldier on duty can use his gun. I placed the negro this afternoon among his friends, and no one need know where that is."