Last updated: January 29, 2025

Person

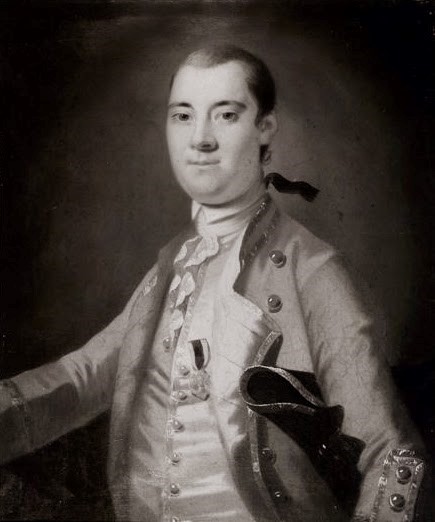

William Tryon

William Tryon, the last civilian royal Governor of New York and North Carolina, was born in Surrey, England on this date in 1729. Coming from a well-off family, it was probably Tryon’s father that purchased him a lieutenant’s commission in the British Army in the 1st Foot Guards in 1751.

He soon after was able to obtain the rank of captain. In 1758, Tryon became lieutenant-colonel of the regiment. He saw action that same year in the Seven Year’s War during raids on the French coast at Cherbourg and St. Malo. In the fighting around St. Malo, Tryon was badly wounded. That same year he married heiress, Margaret Wake.

With the end of the war in 1763, Tryon knew that further advancement in the army would be difficult. Using family connections, he started lobbying parliament for a governorship in the American Colonies. In 1764, he obtained the governorship of North Carolina and arrived there in April with his wife and daughter. Tryon gained a reputation as a fair and able administrator, but while he expanded the Church of England in the colony and created North Carolina’s first postal system in 1769, he is more remembered in the colony for the results of his ruthless ambition. He commissioned the building of a large mansion to act as his home and the center of his administration, raising taxes to fund the project. Many who opposed the large sums of money the mansion was costing sarcastically dubbed it “Tryon Palace” (the original mansion burned in 1798 but was rebuilt per the original plans in the 1950’s and is a historic site today). To protest the rising taxes and the corrupt tax system, the poor farmers on the western edges of North Carolina formed the Regulators, which carried out armed resistance against the government between 1766 and 1771. When negotiations failed, Tryon led the colony’s militia against the Regulators and defeated them in the Battle of Alamance Creek in 1771. Tryon had seven of the ringleaders hanged and raised taxes again to pay for the costs of putting down the rebellion.

In 1771, Tryon secured the governorship of New York. In 1772, William Johnson helped convince the Governor to create a new county that would take in almost the entire Mohawk Valley region up to the Fort Stanwix Treaty line. The new county was named Tryon in the governor’s honor. Tryon again proved an able administrator but found it harder and harder to navigate a middle ground between parliament and the colonists as their resentment with the government grew. Tryon understood that parliament would never be able to successfully tax the colonies and did not even attempt to enforce the 1773 Tea Act, knowing it could only end in violence.

In April of 1774, Tryon departed for England to attend to personal affairs and did not return until June of 1775, after the American Revolution had begun. While the colonies had not yet declared full independence from England, there was little Tryon could do to exert royal authority. After sending his family back to England, he fled in October to a British warship in New York City harbor for his personal safety. He remained there until the British took New York City from the Americans in the late summer of 1776. Tryon was one of the masterminds behind the attempt by turncoat members of Washington’s Life Guard to assassinate him while in New York City. Tryon was also successful early on in convincing large numbers of American soldiers to defect to the British with promises of cash bonuses and land grants.

With New York City under martial law for the duration of the revolution, Tryon had little work as royal governor and he lobbied to return to active military duty. In 1777 he was commissioned a major general in the loyalist forces for the duration of the war. Throughout the war, he would exhibit the same ruthless nature in dealing with the American rebels that he displayed against the Regulators in North Carolina. In 1777, Tryon was given a large force to raid the Continental Army supply depot in Danbury, Connecticut. He was successful, destroying most of the supplies, and in addition, burning the homes of 19 known American rebels. Unlike many English, Tryon fully advocated using Indian allies against the rebels, stating “you have to unleash the savages against the miserable Rebels in order to impose terror on the frontiers.” After the British surrender at Saratoga, he commented that “Much as I abhor every principle of inhumanity . . . I should burn every Committee [of Safety] man’s house.” Tryon also led raids into New Jersey and Westchester Country in the Hudson River Valley.

Tryon continued to advocate for attacks on civilian targets as well as military ones, and in 1779, he was given permission to lead a large land and naval force against several coastal towns in Connecticut. When the attacks were over, Connecticut Governor Johnathan Trumbull estimated that Tryon had destroyed four hundred homes and barns as well as two churches. General Washington sarcastically made note of “the conflagration of Fairfield, Norwalk, & New Haven by the intrepid & Magnanimous Tryon who in defiance of all the opposition that could be given by the Women & Children Inhabitants.” The British had hoped that these raids would force the Continental Army out of their fortifications in the Hudson Highlands, but Washington would not budge. In consequence of this, and the overall brutality of Tryon’s actions, British commander Sir Henry Clinton refused to authorize any further raids.

Tryon was not given any further significant commands and he returned to England in 1780. Suffering from gout, his health prevented him from taking any further service in America. In December 1782, he was promoted to Lieutenant General, and, six years later, he died at his house in Upper Grosvenor Street; ironically, this is very close to the site of the present United States Embassy. He continued in military administration positions and died in 1788.

Image below: A supposed image of Governor William Tryon. There are no confirmed portraits of him from his lifetime.