Last updated: December 27, 2021

Person

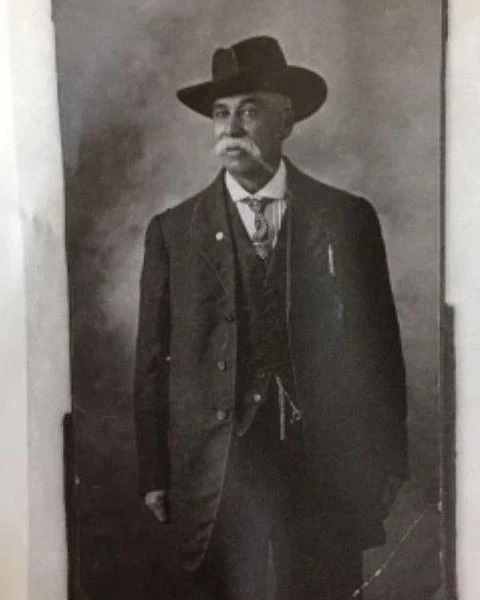

William Parker Walker

Joyceann Gray

William Parker Walker was born in 1831 to George and Margaret Ann who decided to take the last name of their benefactor, Walker, as a symbol of their appreciation for all they have shared with them and the protection they provided. Ohio was not a slave state, but enslavers were allowed to come and reclaim any runaways. Living among the Quakers continued to be a haven for all the Walkers.

Years later, William Parker, at sixteen, had become a sailor on Great Lake Steamers and was known through the underground as one who would help runaway slaves reach Canada. Along the route was a port at Windsor, Canada and it was during a layover there that William learned of the Buxton settlement. He was an educated man in knowing how to read and write and was trained by his father in the Coopers Trade (the making of wooden barrels). A yearning for life on land led William along with his family to relocate to Buxton and safety, as the Ohio Black laws of 1807 became a political issue once again. To stay in Ohio, Blacks had to prove that they were not slaves and to find at least two white people who would guarantee a surety of five hundred dollars for their good behavior. This made the Walkers very nervous.

In Buxton, the Walkers flourished and found a sense of peace. William won the appointment of Postmaster of Buxton-Kent, Ontario, Canada and performed the duties of Superintendent of the Sunday School. He also led many of the prayer meeting services. In 1860, Private Redmon Caddin, in Captain Corries Company, South Carolina Militia during the War of 1812 was awarded a 160-acre tract of land in Johnson County, Nebraska. (Under the March 3, 1855: Scrip Warrant Act of 1855 (10 Stat. 701)). He then sold it to William P. Walker. The reason isn’t clear for the transaction, but this sparked William’s initial decision to return across the border along with Isaac Riley and his son William King Riley, joined with Bill Tann and Joshua Emanuel and about six other families and headed back across the border after the end of the Civil War in search of enough land that would provide them safety and peace.

The Walker group started their homesteading quest in Johnson County, Nebraska in 1880. By this time, Walker was married to Sarah Kersey and their family had grown to include five children. Walker made application for homestead entry on the 26th of March 1880. It was during that spring and summer of 1880, to meet the requirement of improving the land, Walker housed his family with neighbors until he could build a house suitable for his wife and five children.

That first year was the driest year Nebraska had seen in many years. There was no rain in which to help make sod bricks for building, so Walker had to dig a well that reached 68 feet before water began to flow. Walker spent many a night sleeping under the open sky and working during the day. He built a shed for his oxen to protect them during the coming winter months. He built a chicken coop, planted a vegetable garden, and plowed and planted 40 acres of wheat and from 25 to 40 acres of corn. Walker was only able to get the walls of his house built and store up wheat for his oxen before he ran out of time and money.

Winter had set in, so everything had to wait until the first thaw of 1881. May of that year William P. was able to bring his family to the newly built 14 x 30-foot home in Township 9 and Range: 09 North, 19 West, Overton, Dawson County, Nebraska. A flourishing garden and acres of planted wheat and corn were the fruit of his labor along with the help of his friends William King Riley, Elijah Tann, and Joshua Emanuel. These men had known each other for many years in Canada. What they did in Overton was just a repeat of what they did years ago in Buxton, Ontario, Canada.

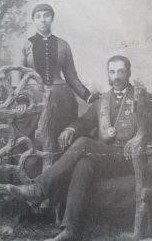

Sarah and William Walker

Photo Credit: Joyceann Gray

Walker’s wife Sarah Catherine worked right alongside of her husband when time permitted. She gave birth to six beautiful strong babies but sadly just after giving birth to her last one she suddenly died January 1891. Per Sarah’s wishes Walker took her home to Canada and buried her next to her parents in North Buxton, Chatham-Kent Municipality, Ontario, Canada. This left William alone with six children and a busy farm. The Walkers were sticklers about education, their oldest Amos was in Normal school and wanted to come home and help his father, but Walker insisted he remain in school and help around the farm on the weekend. Neighbors came to support Corena and Eva Ann the two oldest girls maintain the house and care for the younger children.

Almost to the day a year later William King Riley, one of Walker’s best friends passed away after a fall. William King left a wife, Charlotta Riley and three young boys.

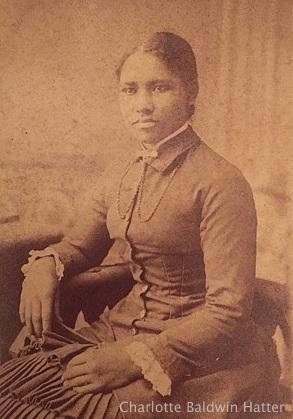

Charlotta Hatter

Photo Credit: Joyceann Gray

Charlotta was a strong woman but understood that she needed help with their land and all. Two years later, William P. Walker and Charlotta Hatter Riley were married on May 12, 1894. With nine children the house was full. Eventually though, they welcomed four more children to their family. Charlotta nourished her family and taught each child to read and write. She was a great storyteller but not quite as exciting as her husband was. Whenever neighbors would stop by or there was a celebration of sorts, Walker would be the one to put the children in a trance with his exciting stories.

By 1914 William P. and Charlotta had purchased a total of 1,920 more acres in Cherry and Dawson Counties with the help of the increase of acreage a person could apply for under the Kincaid Act of 1904.

Early in the 1890’s, The Walkers changed from farming to cattle raising. Walker became the unofficial community veterinarian with a special touch for the horses.

The Walker family and other homesteading neighbors stand in front of the Walker's home after a prayer meeting. The home was built by Walker and his son Elehugh, Ha Shrill, Chris Stith and John Williams.

Photo Credit: J. Gray

Education was a priority in DeWitty, and all the children were taught to reach for more and indeed they did. The Riley boys first choose was to farm and raise cattle. Late in 1938, Albert Riley sold his land and went to work as manager at the Valentine Wildlife Refuge. William Riley, Charlotta’s grandson became the first Black locomotive engineer in Bailey Yard, North Platte, Nebraska. He was honored along with such notables as Buffalo Bill Cody and Ed Bailey in Bailey Yard’s Hall of Fame, on display at the Golden Spike Tower and Visitor’s Center. Amos Walker, in 1899 received his bachelor’s from the University of Nebraska Teachers’ College. He moved to Missouri and enjoyed a very successful teaching career at Lincoln College in Missouri. Baldwin became an engineer at the Dupont plant, Sweet became a nurse in Kansas, Fernnella became a teacher as did Goldie who went on to become a Principal in Norris, S.D. And the list goes on and on.

The land eventually was sold off to the larger ranchers as these first homesteaders aged and moved to be closer to their children. Their children had spread their wings and traveled far and wide from Nebraska to Missouri, Kansas, California and even as far as Paris, France.

~ Contributed: Joyceann Gray

Joyceann Gray

Photo Credit: J. Gray

More about the contributor: Joyceann is the granddaughter of Goldie G. (Walker) Hayes. She is the great granddaughter of William P. and Charlotta Hatter Walker. Once retired from the Army, she has devoted much time researching her family history and authoring two books.

‘Yes, We Remember’ is devoted to the historical accountings of her ancestors, ‘DeWitty and Now We Speak’ is a historical fiction about the women of DeWitty, Nebraska where her maternal family first homestead. Joyceann is a Contributing Writer of many Notable African Americans and Ambassadors on BlackPast.org. She holds memberships in local genealogical societies and the Charles Town, WV Researchers. Joyceann was an integral part of the Descendants of DeWitty who not only helped raised money but facilitate the erecting of the Historical marker along Hwy 83, near Brownlee, Nebraska, April 2015. Of late, Joyceann is busy supporting the historical and genealogical research of The Whitetop Tribe of Native Indians and writing the stories of her ancestors who were homesteaders in Nebraska.

Patent Details - BLM GLO Records

Stith, F. M. (1973). Sunrises and sunsets for freedom. New York: Vantage Press.