Last updated: April 23, 2025

Person

Sgt. William Jones

The Public Archives of Canada

William Jones was born circa 1748 in Hardwick, Sussex County, NJ. He had a fair complexion, stood 5’ 5½”, and had brown hair and blue eyes. He was a “cordwainer” (or shoemaker) by trade and literate. He was a Baptist. His family appears to have direct connections to Abergavenny, Monmouth, England near the border of Wales.

On November 26, 1776, despite his familial links to Britain, he enlisted for three years in Captain Leonard Bleeker’s Company of the 3rd NY Regiment. In spring of 1777, the regiment marched to the border of new nation and garrisoned the new American Fort Schuyler (formerly known as Stanwix).

In summer of 1777, British forces began to bear down on New York and the fort’s soldiers that stood at its edge. Over the course of July, several little girls were scalped and killed within proximity of the garrison, several men and an officer were captured by British-allied Native forces, and half a dozen others were injured, mutilated, or killed by the same. The families of the soldiers were sent away as a precaution. Jones and his now pregnant wife Mercy would’ve had a tearful and uncertain goodbye, not knowing what would become of them as the tide of war shifted against them. In August, all of this came to a head when nearly 3,000 British and British-allied forces surrounded and besieged the fort and its garrison for three weeks before being deterred and fleeing back to Canada. It was a remarkable victory on the part of the 3rd NY Regiment who were later commended by Congress for their efforts in holding the fort and the border.

The regiment and Jones remained stationed at the fort for another year before being relieved of their post in late fall 1778. In 1779, the entire regiment was sent to participate in the brutal Sullivan-Clinton Campaign against the Haudenosaunee people. As well as participating in multiple raids of and the destruction of many Native village, Jones and his fellow soldiers fought in the Battle of Newtown in August of that year, in which the British-allied forces of Walter Butler and Joseph Brant were defeated.

When November 1779 rolled around and Jones’ term was up, he chose not to reenlist. His discharge papers were signed by Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willett himself, with all pay debts to Jones settled. He was 31 years old. It is assumed he returned with his wife and infant son James to New Jersey. It is unknown what he did for the remainder of the war.

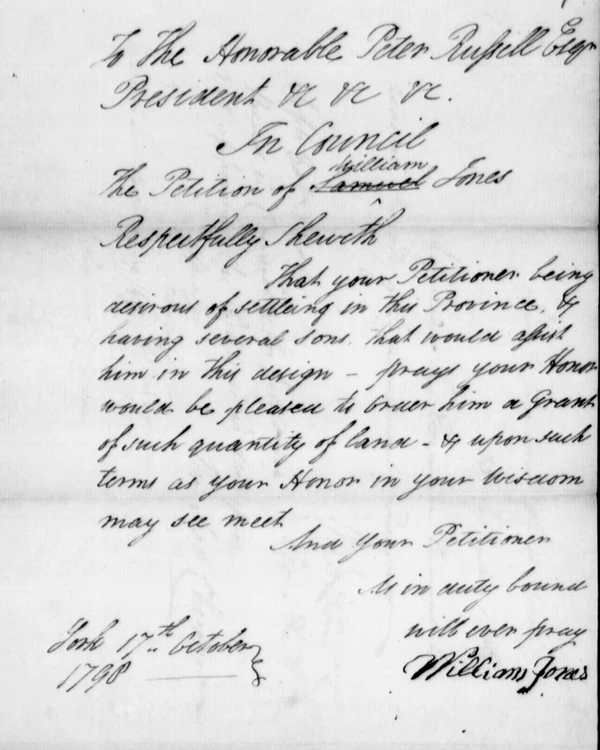

At some point in 1796, now the father of seven children with wife Mercy now living in Owego, PA, Jones chose to petition the Canadian Provincial Government in York for land. That request was denied, but Jones and his family still ended up moving to the north and settling in the British Loyalist village of Scarborough, Ontario, (West) Canada. There the family spent the rest of their lives, Jones’ children establishing new roots in the community; occasionally attending a Presbyterian church despite being a Baptist. In their old age, they lived with their daughter Elizabeth, her husband Jacob Brooks, and an unmarried older woman, Mariah Hamlin, who all took care of them.

Jones passed away at 6 a.m. on January 1, 1833, with his daughter to comfort him in his final hour. Two days later, Elizabeth gave birth to a little girl and buried her father. Several weeks later in March his widow, Mercy, passed as well.

Little more than a decade later, their surviving children (William Jr., James, Mary, and Elizabeth) sent a surrogate to New York State to file for a widow’s/survivor's pension, using Jones’ original discharge papers as proof of his service and multiple depositions proving their relationships. Over the course of the next five years, the surrogate advocated on their behalf. The petition however, was denied, presumably because of Jones’ eventual abandonment of the new nation he had once served.

Jones' story is a curious one. Why would a well-regarded soldier for the Continental Army, fighting for his nation’s independence just up and leave the only home he’d known to go and live with “the enemy”? Perhaps it was his family’s ties to England? Perhaps it was opportunity? What circumstances led his children to try and claim his service to a nation he hadn’t lived in in 30+ years when he passed? James and William Jr. had fought with Canadian militias during the War of 1812 and received Canadian veteran's pensions in their own right. They clearly had no personal attachments to the United States.

The actual reasoning behind these curiosities will likely never be answered. What it comes down to is the fact that human nature is complicated. As was the relationships, alliances, and decisions made by the regular people who lived through the American Revolution.

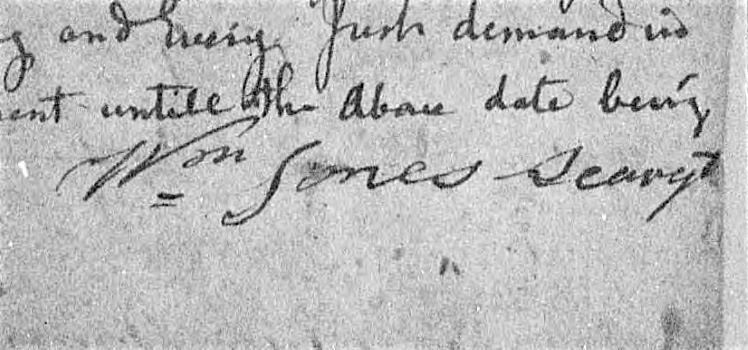

Image below: An up-close cropping of William Jones' signature from his 1779 discharge papers.

Sources

-

Canada Land Petitions, wjw Bundle 7, 1804-1806. Microfilm record C-2109. Canada Public Archives.