Last updated: March 20, 2025

Person

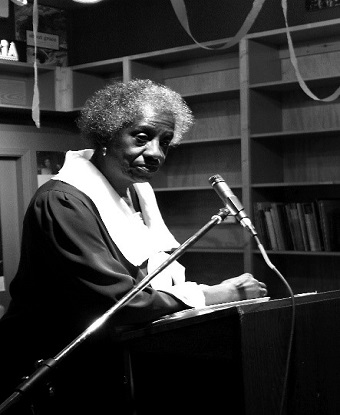

Unita Zelma Blackwell (1933-2019)

Photo by William Patrick Butler.

Born to sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta, Blackwell rose from humble beginnings to become one of many unsung Black female heroines of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Forced to leave school when she was 12 to earn a living, Blackwell would later become an outspoken critic of racial and economic inequality and the first Black female mayor elected in the state of Mississippi. We honor her as an ancestor for reminding us of the power to change the circumstances we were born into.

Blackwell’s entrance into political activism seemingly happened overnight. A few months after starting to work in the cotton fields, picking cotton for $3 a day, activists from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) came to Mayersville, Mississippi in June 1964. The two activists held meetings in the church she belonged to about the rights of Black Americans to vote. They wanted to recruit residents to organize a voter registration campaign. Despite being in one of the South’s most repressive states, the following week Blackwell and seven others went to the courthouse to take a voter registration test. In Mississippi, registering to vote could result in death for Black people. While outside waiting, a group of white farmers attempted to intimidate them into leaving. Only two of them could enter the courthouse and neither was told whether they passed the test or not. Blackwell and her husband, Jeremiah, lost their jobs the following day after their employer found out that they attempted to register to vote. As a result, Blackwell and her family were left without a steady income and were denied welfare payments. SNCC sent them $11 every two weeks and members of the community would give the family food. Later writing about the incident, Blackwell stated, “…what happened outside the courthouse that day was the turning point in my life.”[i] Over the next few months, Blackwell attempted to pass the discriminatory test three times. In the fall of 1964, she passed and became a registered voter. The following January, she testified in front of the United States Commission on Civil Rights about her experiences.

Committing herself to social change, Blackwell joined SNCC after meeting Fannie Lou Hamer in summer 1964. Hamer would become lifelong friends with Blackwell and serve as her mentor for community organizing and freedom fighting. Working alongside Hamer, Blackwell founded the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party in 1964. Founded as a challenge to the whites-only Democratic Party, it had two goals: first, to establish laws preventing Black children’s employment as sharecroppers; second, to establish black schools that would teach mathematics and science. Though they failed in unseating the Democratic Party at the national convention, they gave Black Americans the first ever opportunity to participate in political action.

In 1964, Blackwell co-founded the Mississippi Action Community Education, a community organization which helped districts incorporate as towns. By setting geographical boundaries, this legal identity aided districts in securing government funding. In 1976, Blackwell was elected mayor of Mayersville. She was the first Black woman elected as a mayor in the state of Mississippi. Through her incorporation of the town, Blackwell was able to initiate programs to assist the poor, as she had while working with the National Council of Negro Women. Before being elected as mayor, Blackwell worked with the NCMW in the early 1970s to provide food and housing for rural families through programs like the Pig and Garden campaign. These efforts led to home ownership and improved social services for residents. Through her efforts, she was able to obtain federal grant money to get Mayersville a police and fire department, a public water system, paved streets, housing for the elderly and disabled, and other infrastructure. Blackwell served as mayor from 1976-2001. She was elected to chair the National Conference of Black Mayors in 1989 and as president from 1990-1992.

Blackwell continued to be a voice for working rural families. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter selected her to participate in the national Energy Summit held at Camp David, Maryland. Recognizing the need to have educational credentials to continue her rural community development work, she applied for the National Rural Fellows Program. She was selected out of 100 applications, and at 50 years old Blackwell began studies at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1982. She graduated the following year with a master’s degree in regional planning. In 1992, Blackwell was awarded a $350,000 MacArthur fellowship for her efforts to create the Deer River housing development.

As a result of her participation in the Civil Rights Movement, Blackwell was arrested over 70 times. Yet, her commitment to racial uplift remained unwavering. Reflecting on her own humble beginnings and activism, she stated, “I’m proof that things can change.”[ii] Unita Blackwell epitomizes the power of community-based efforts and of Black women in the Civil Rights Movement to enact change at the local and regional level. This essay on Unita Blackwell is the fifth installment of the “Exploring the Meaning of Black Womanhood in America: Hidden Figures in NPS Places” series. She is associated with the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site in Washington, D.C.

This article is part of the "Exploring the Meaning of Black Womanhood Series: Hidden Figures in NPS Places" written by Dr. Mia L. Carey.

LEARN MORE:

Blackwell, Unita and JoAnne Prichard Morris. 2006. Barefootin’: Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom. New York City: Crown Publishers.

Hine, Darlene Clark. 2005. Unita Blackwell. Black Women in America: Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. P. 145-146.

Kilburn, Peter T. 1992. A Mayor and Town Rise Jointly. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/17/us/a-mayor-and-town-rise-jointly.html, accessed July 12, 2020.

[i] Blackwell and Morris 2006: 7

[ii] Hine 2005: 146