Last updated: June 20, 2024

Person

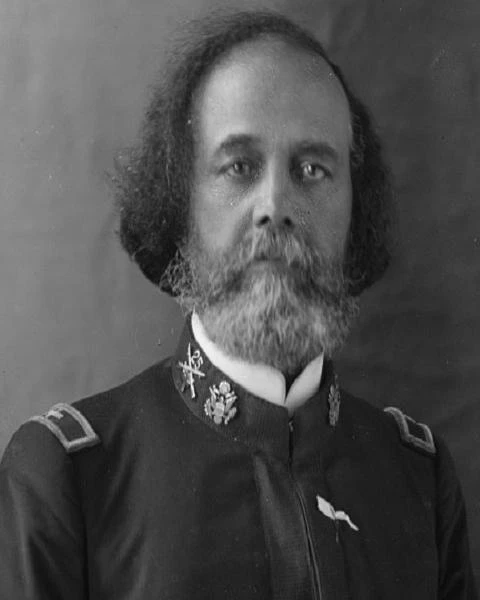

Theophilus Gould Steward

courtesy of the Library of Congress

Theophilus Gould Steward was born on April 17, 1843, in Gouldtown, New Jersey. His family belonged to the Gouldtown African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. His mother, Rebecca, read the Bible to him and his siblings to supplement their education. She also read them the local newspaper to keep them informed of local and global events. Steward enjoyed the stories from the West, including updates from the Mexican-American War. Those stories sparked his interest in travel.

Steward attended the Bridgeton School in Gouldtown during winter months and worked the rest of the year to help his family. He also attended lectures at the Gouldtown Literary and Moral Improvement Society. There he learned more about literature, politics, and philosophy. He wanted to serve others and decided to pursue a career as a pastor. The Reverend Joseph H. Smith, pastor of the Gouldtown AME Church, mentored him in this pursuit.

On September 26, 1863, Steward was ordained as a minister and served in his hometown. On June 4, 1864, he attended the AME Church’s Philadelphia Annual Conference. He expressed a desire to serve in the South but was advised against it because of the ongoing Civil War. Instead, he was appointed as pastor of the Macedonia AME Church in South Camden, New Jersey. After the Civil War, Steward was one of the first AME pastors selected to serve in the South.

On May 13, 1865, he arrived in Charleston, South Carolina. He worked with the U.S. Army and the Freedman’s Bureau to set up schools and religious programs. On June 27, 1867, he left Charleston for Macon, Georgia, to continue this work. On route, he befriended Civil War veteran and future U.S. Representative Robert Smalls. Smalls was born enslaved and during the Civil War, he was forced to work for the Confederate military. He used this knowledge to commandeer the CSS Planter and escape to federal lines. His daring efforts helped persuade President Abraham Lincoln to accept African Americans into the Federal Army.

Steward served at the first AME Church in Macon and established a school for the children there. In 1872, Steward's oversaw the rebuilding of the church, which had been desteroyed by a fire several years earlier. The congregation renamed it “Steward Chapel AME Church” in honor of the man who led its reconstruction.

Between 1872 and 1881, Steward worked to expand the AME Church in South Carolina, Georgia, Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, and Haiti. In 1881, he earned his Doctor of Divinity degree from Wilberforce University in Wilberforce, Ohio. Through his work, Steward gained support from prominent African American leaders including Frederick Douglass, Representative Robert Smalls, and the Reverend Francis J. Grimké.

In February 1891, the chaplaincy of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry was vacant. Former Congressman John R. Lynch of Mississippi recommended the Reverend Grimké for the position. Grimké declined the post and recommended Steward. Pursuing the position, Steward received recommendations from Frederick Douglass, Congressman Blanche K. Bruce, and Postmaster General John Wanamaker. On July 25, 1891, Steward was appointed the first African American chaplain of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry by President Benjamin Harrison.

On August 24, Steward arrived at Fort Missoula, Montana. He was in charge of the school, the library, and the soldiers’ religious and education services. Shortly after his arrival, he wrote “I became possessed of the army spirit and identified myself with its discipline and training as well as its outdoor life.”

Chaplain Allen Allensworth of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry praised Steward's work. Chaplain Allensworth stated, “your church needed just such a man to represent it in the army [for] … you have but little idea how much good for the race and cause of Christ, he can and is doing where he is, as chaplain.” Colonel George Leonard Andrews of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry praised Steward as well. Colonel Andrews wrote that Steward was “well educated, gentlemanly, refined and respected by all. He has assumed his duties with zeal and prosecuted them with intelligence and the results will be satisfactory.”

Chaplain Steward advocated for racial equality through his sermons and writings. In 1895, he wrote an essay titled “The Colored American as a Soldier,” in which he argued for racial equality in the Army. In the essay, Steward quoted Brigadier General Wesley Merritt who stated, “the day will come when there will be no more colored soldiers in the army … but the special defenders of the flag shall simply be Americans-all.”

Steward praised the Army for the educational and career opportunities it afforded to young people. He urged young African American men to become commissioned officers. He cited Henry Ossain Flipper, John Hanks Alexander, and Charles Young – all graudates of the United States Military Academy at West Point who became U.S. Army officers – as examples of what they might accomplish.

On March 9, 1896, Steward applied for the vacant chaplain position at West Point. He stated “owing to my color, I believe my presence … would tend to promote a breadth of character, and develop a truly American spirit” as the reason he sought the post. However, his commanding officer Colonel A. S. Burt, declined to endorse his application, preventing him from achieving his goal.

On March 29, 1898, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry received orders to report to Chickamauga, Georgia, for training. On April 10, as the Twenty-Fifth Infantry departed Fort Missoula, they were celebrated by Missoula’s citizens. The Daily Missoulian reported, “the fortunes of the [men] will be followed with intense interest by the people of Missoula.” On April 14, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry arrived at Chickamauga, but their stay was brief.

On April 21, 1898, the United States declared war against Spain. The Ninth Cavalry joined the Twenty-Fifth Infantry at Chickamauga in preparation for the fight. On April 24, Steward and Chaplain George W. Prioleau of the Ninth Cavalry led religious services for both Buffalo Soldier regiments. They calmed the nerves of the soldiers by reading Bible verses.

In May, Steward was assigned to Dayton, Ohio to help recruit volunteers for the various all-Black volunteer regiments. This included the Ninth Ohio Battalion, Eighth Illinois Infantry, and the Ninth and Tenth U.S. Volunteer Infantries. While in Dayton, Steward learned of Lieutenant Charles Young’s appointment as Major of the Ninth Ohio Battalion. Steward reflected on Young’s promotion as a symbol of future opportunities for African Americans. He took leave to attend Major Young’s appointment celebration in Xenia, Ohio.

On July 5, Steward wrote to the War Department about his desire to return to his regiment and assist in the war effort. He requested to “be placed on duty at … one of the hospitals where our wounded men are, until … I can get to my regiment.” On August 2, he received orders to rejoin the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Regiment in Cuba. However, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry departed Cuba and were on their way to Camp Wikoff in Montauk Point, New York. On August 13, Steward received updated orders to proceed to Camp Wikoff.

On September 18, Steward was invited by the Montauk Soldiers’ Relief Association to speak at the Bridge Street AME Church in Brooklyn, New York. Inspired by the soldiers who served in Cuba, Steward advocated for more African American officers in the Army. He stated, “we will need an army of 100,000 for Cuba… Cuba will afford a field for Negro colonels and brigadier generals.” During this time, he also started writing a book, “The Colored Regulars in the United States Army.” It highlighted the accomplishments of the all-Black regiments during the Spanish-American War. However, the war delayed the book’s publication until 1904.

In October 1899, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry was assigned to Manila, Philippines. Steward joined the unit and provided religious services as well as cared for the sick. He was also assigned the superintendent of the Filipino schools. Steward modeled the education system after that of the United States and worked with communities to establish new schools. On July 4, 1901, Civil Governor of the Philippines William Howard Taft announced that 1,000 American teachers were to be recruited to teach in the new schools by October. Steward was excited to learn that his son, Gustavus Adolphus Steward, was one of the teachers. By January 1902, Steward established 43 new schools across the Philippines.

On January 21, he was relieved as superintendent when a civil commission act terminated United States military control in the Philippines. On July 7, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry returned to the United States and was assigned to Fort Niobrara, Nebraska. At Fort Niobrara, Steward organized classes on American history, Spanish language, and civil government. He also traveled with soldiers during training, baseball games, and band performances. In May 1906, Steward was assigned to Fort McIntosh in Laredo, Texas, when the Twenty-Fifth Infantry was assigned to various forts in Texas.

On October 5, Steward was admitted into the military hospital at Fort McIntosh. He suffered from fatigue and was deemed unable to travel. On October 22, he was granted a three-month leave to visit his brothers in Bridgeton, New Jersey, as he continued to recover.

On December 10, Army surgeon, Dr. W. T. Good, was assigned to treat Steward in Bridgeton. On January 10, 1907, Dr. Good informed the Army that Steward was unfit to travel “or follow his usual vocation.” On January 12, in anticipation for his retirement, Steward requested the Army assign him to Wilberforce. On February 1, the War Department ordered Steward to Wilberforce to await his retirment.

On April 17, 1907, Steward retired from the Army after 16 years of service. He was a devoted patriot who advocated for education and equality. Many young soldiers were inspired by his work in the Army, and his retirement was a loss to young African American recruits.

In 1908, Steward chose not to return to the AME Church but instead to remain in Wilberforce, where he taught history, French, and math at the university. He supported the work of Carter G. Woodson, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Emmett J. Scott as they wrote African American history books. Steward was close to Charles Young who also lived in Wilberforce and had previously taught at the university.

In 1918, Steward retired from Wilberforce University. In 1921, he published his autobiography “From 1864 to 1914: Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry". Energized by the book's success, he continued to lecture in Ohio, New York, and New Jersey.

On January 11, 1924, Theophilus Steward died in Wilberforce, Ohio. He was buried in Gouldtown Memorial Park in Gouldtown, New Jersey.

Additional Resources:

Clasrud, Bruce A, and Michael N Searles. Buffalo Soliders in the West: A Black Soliders Anthology. College Station, TX: Texas A & M Univ Press, 2007.

Seraile, William. Voice of Dissent: Theophilus Gould Steward (1843-1924) and Black America. Brooklyn, NY: Carlson, 1991.

Steward, Theophilus Gould. From 1864 to 1914: Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry. Twenty-Seven Years in the Pastorate; Sixteen Years’ Active Service as Chaplain in the U.S. Army; Seven Years Professor in Wilberforce University; Two Trips to Europe; a Trip to Mexico. Philadelphia, PA: Printed by A.M.E. Book Concern, 1921.

Steward, Theophilus Gould. The Colored Regulars in the United States Army, with a Sketch of the History of the Colored American and an Account of the Country from the Period of the Revolutionary War to 1899. Philadelphia, PA: A.M.E. Book Concern, 1904.

Taylor, Quintard. Buffalo Soldier Regiment: History of the Twenty-Fifth United States Infantry, 1869-1926. Lincoln, NE: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2001.