Last updated: January 16, 2023

Person

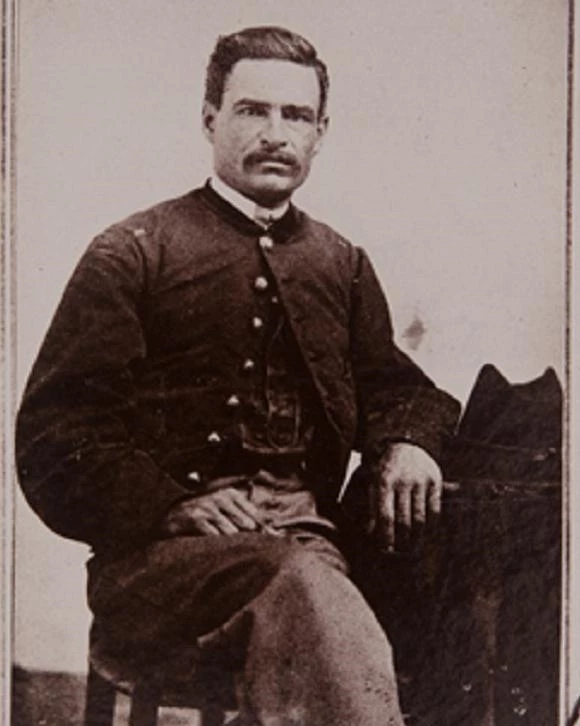

Stephen Swails

Massachusetts Historical Society

As a soldier, reformer, and politician, Stephen Swails showed commitment to equality, placing him at the forefront of radical change in American race relations.

Born in Columbia, Pennsylvania in 1823, Swails grew up in south central Pennsylvania and western New York. In the years before his birth, Swails’ parents, freed persons from the slave state of Maryland, moved the family from the dangerous border state to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Following the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, abolitionists and slave catchers frequently fought over the area.1 To avoid additional risks, Swails and his family relocated to the abolitionist center of Elmira, New York.

Swails worked as a waiter in Cooperstown, New York in April 1861 when the Civil War began.2 Swails shared the desire to serve in the war with other African American men who realized that it could radically change their status in the United States. However, the government prohibited their enlistment until the Lincoln administration issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which paved the way for Black men to serve in the military. Massachusetts soon began recruitment for the 54th Regiment, one of the first Black regiments of the Civil War, and enlisted the help of abolitionist leaders including Frederick Douglass to help fill its ranks. Douglass toured the Elmira area in the winter of 1863 as part of his recruitment tour. Likely inspired by Douglass‘s recruiting drives, Swails and hundreds of African Americans from New York and Pennsylvania enlisted in the new 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. They trained at Camp Meigs in the Boston area before heading to the warfront.

Recognizing Swail’s leadership ability, the regiment’s young colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, quickly promoted him to 1st Sergeant. During the 54th's heroic assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, Swails cradled the body of K company commander as he died and rallied the retreating regiment.

A defining moment for Swails came at Olustee, Florida on February 20, 1864. During the battle, he rallied the regiment and retreating Union forces, receiving a serious wound.3 While the 54th commanding officer recommended Swails for a promotion to 1st Lieutenant, racism within the military slowed the promotion for nearly a year. Despite emancipation and the disintegration of slavery, the basic idea that a Black man could lead White troops in battle struck at the heart of American racist attitudes. Captain Luis Emilio wrote, "When the usual request was made, it was refused on account of Swails African descent, although to all appearances he was a white man."4 White officers in the regiment, such as Lt. Charles During, struggled to reconcile their own racism with the heroism of Black soldiers they witnessed on the battlefield and their belief that African Americans should not give orders to White soldiers.5 White officers gradually came to view their Black comrades with respect as they witnessed their bravery in battle. In January 1865, Swails finally received official promotion to officer rank. Though likely the only Black officer to receive this promotion, Swails never officially commanded in combat as the war soon ended without another major military engagement for the 54th.6

Reconstruction enabled Swails to rise to political prominence in post-war South Carolina. Elected to the state senate in 1868, he served continually for nearly 10 years. Swails became the most prominent member of the South Carolina senate, the president pro tempore, placing him in control of all bills that passed through the state legislature.7 Committed to universal education, he played a critical part in transforming The South Carolina College from a school for planter elite into the integrated University of South Carolina.

Support for the Reconstruction governments faltered despite Swails’s direct appeals to President Grant in 1872. Local militias violently overthrew the state’s Reconstruction government in 1876, and the final federal troops withdrew the next year. The restoration of the former Confederates to power ended Black political influence in the state. Some Black politicians, including Swails, continued to have local influence, however the leadership of the state targeted his reputation and his life. In 1878, he survived two assassination attempts, forcing him to limit time in the state.8 Despite continued threats, Swails returned to South Carolina in 1884 to run for Congress. Unable to campaign due to the danger, he lost the election.

Swails died in Kingstree, South Carolina on May 17, 1900. His gravesite in the segregated Humane and Friendly Society Cemetery in Charleston remained unmarked until the 1970s.

Lt. Swails’s life spanned the dramatic change in American history from slavery to Black political power in the South. Although he died at the beginning of the long Jim Crow era, his life and accomplishments foreshadowed the continued fight for civil rights throughout the 1900s and 2000s that remains ongoing today.

Footnotes:

- Douglas R. Egerton, Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that redeemed America (New York: Basic Books, 2016), 20.

- Egerton, 20.

- Egerton, 228.

- Luis Emillo, A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the 54th Massachusetts, 1863-1865 (New York: De Capo Press, 1995) 194.

- Egerton, 229.

- Egerton, 267.

- Egerton, 326.

- Egerton, 327.