Last updated: March 30, 2025

Person

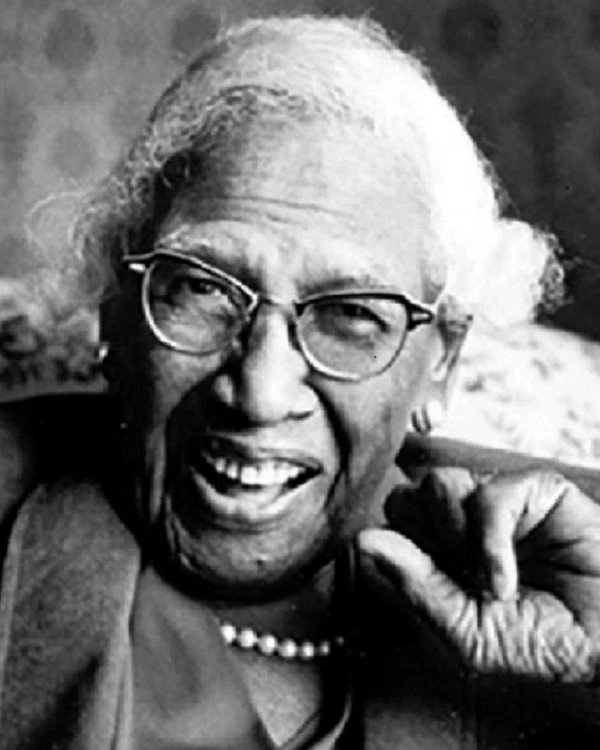

Rosina Corrothers Tucker

Credit: Unknown

A civil rights and labor activist, Rosina Corrothers Tucker played a pivotal role in the creation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) and its International Ladies’ Auxiliary Order. Her influence within these organizations challenged the limits often imposed on African American women who sought to lead movements for racial and economic justice in the early to mid-twentieth century. Tucker’s experience with the BSCP led her to organize other groups of workers, including women in the laundry trades and domestic service industries. She was also a leader in the fight to integrate public spaces in Washington, D.C., and advocated for the rights of children and the elderly.

Rosina Budd Harvey Corrothers Tucker was born November 4, 1881 to Lee Roy and Henrietta Harvey. In 1898, she married James David Corrothers, a minister, journalist, and poet. The couple moved frequently until Corrothers’ death in 1917. Tucker then returned to Washington, D.C., where she would live the rest of her life. In 1918, she married Berthea J. Tucker, a Pullman porter.

In 1925, Rosina Corrothers Tucker attended an organizing meeting in Washington, D.C. led A. Philip Randolph, who had recently co-founded the BSCP in Harlem. At the time, the Pullman Company employed more African American men then almost any other business in the United States. Many African American women also worked for the Company, as female attendants and maids. Tucker became an advocate for the union. She helped create a local chapter in Washington, D.C. and also led efforts to establish a Women's Economic Council in the city. Located in towns across the nation, the councils, raised money and community support for the BSCP. Their contributions proved critical to the union’s survival.

During its formative years, women like Tucker were key to the BSCP’s organizing efforts. The Pullman Company closely monitored employees' activities and punished those who supported the union. The BCSP suspected that women would be subject to less scrutiny than men. As a result, it was often the family members of porters or women employed by the Company who carried out home visits or shared literature about the union.

In 1935, the American Federation of Labor finally granted the BSCP a charter, the first time the nation’s leading labor organization had ever recognized an African American union. Two years later, in 1937, the BSCP signed an initial contract with the Pullman Company. The agreement raised salaries, decreased hours, and introduced a grievance process. In the decade that followed, the union’s membership grew significantly as did membership in the Women’s Economic Councils (now formally renamed the International Ladies’ Auxiliary Order).

In 1938, Tucker was elected International Secretary Treasurer of the Ladies’ Auxiliary Order. Halena Wilson, who had led the Chicago Women’s Economic Council, became President. The formal creation of the Order marked a significant moment in the recognition of African American women’s contributions to the BSCP and the broader labor movement. However, this recognition did not always go uncontested, with men often challenging the authority and organizing skills of the International Ladies’ Auxiliary Order and its leaders.

Tucker’s contributions to labor and civil rights extended well beyond the BSCP. In the early 1940s, she played an important role in the March on Washington Movement, which challenged segregation in the armed forces and defense industry. She also organized locally in Washington, D.C. both to boycott businesses that refused to hire Black employees and to create unions for women working in the laundry and domestic service industries.

Tucker’s activism continued throughout her long life. Widowed in 1963, she remained active in her church community and in local politics. In 1982, she contributed to the documentary Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggles, which chronicled the creation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and its International Ladies’ Auxiliary Order. In addition, she authored an autobiography, "My Life As I Lived It." Rosina Corrothers Tucker passed away on March 3, 1987 at the age of 105.

Bibliography:

Chateauvert, Melinda. “A Sister in the Brotherhood: Rosina Corrothers Tucker and the Sleeping Car Porters, 1930 – 1950,” in Sister Circle: Black Women and Work, edited by Sharon Harley and the Black Women and Work Collective, 184 – 198. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

_____. Marching Together: Women of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Pfeffer, Paula. "The Women Behind the Union: Halena Wilson, Pfeffer Tucker, and the Ladies' Auxiliary to the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters." Labor History 36, no. 4 (1995): 557-578.

Smith, Jessie Carney, “Rosina Corrothers Tucker, 1881 - 1987: Labor organizer, social and civil rights activists, educator." Encyclopedia.com, accessed July 20, 2020, www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/tucker-rosina-1881-1987.

This project was made possible through the National Park Service by a grant from the National Park Foundation through generous support from the Mellon Foundation. The Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship program is administered through a partnership between NPS, NPF, and American Conservation Experience.