Last updated: April 12, 2024

Person

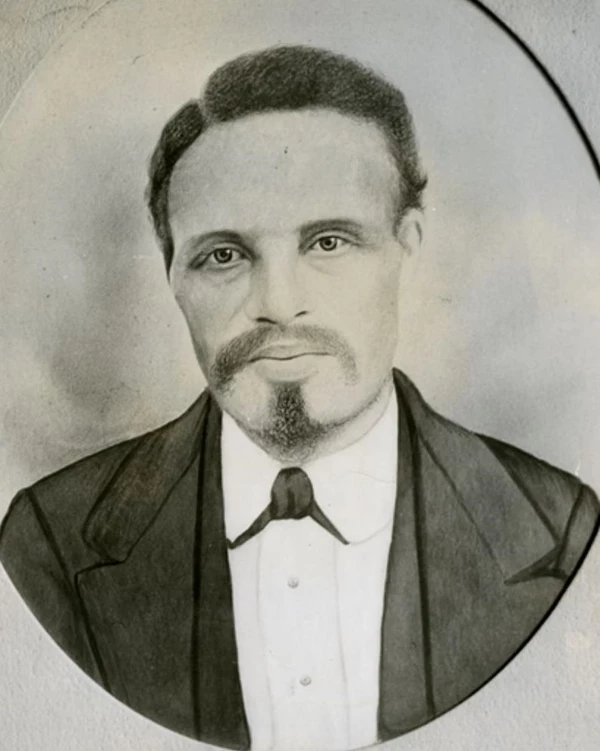

Reverend Robert Hickman

Minnesota Historical Society

Robert Thomas Hickman was born an enslaved man near Boone, Missouri in 1831. With permission of his enslaver, Hickman learned to read and write. This allowed him to preach to fellow enslaved people on several plantations becoming a leader to them. Thus he led a group of Black men and women to freedom in 1863 via the Mississippi River.

The Emancipation Proclamation, January 1863

Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 because the Confederate States who had seceded from the United States refused to return to the Union. This proclamation declared free all the people who were enslaved in the Confederate States. As outlined in the Emancipation Proclamation, the proclamation did not extend to include border states because they accepted Lincoln as president. This meant that enslaved people in border states, such as Missouri, would not be granted legal freedom from their enslavers under the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Journey, May 1863

Robert Hickman and a group of about 75 Black men and women decided to seek freedom from their enslavers by their own accord after the Emancipation Proclamation did not extend to include them. They wanted to work as free people in the northern states. Due to the dangerous nature of Confederates, Hickman and his group from Boone County decided to travel on a simple raft up the Mississippi River during the night in May of 1863. The raft, however, floated on the water and did not get them as far as they hoped because they did not have any tools to help them paddle the waters of the Mississippi River.

As noted in The Children of Lincoln: White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity in Minnesota by William D. Green, in May of 1863 a steamboat called Northerner was on its way to Saint Paul, Minnesota to forcefully transport Dakota people out of Minnesota by orders of the United States government. On its way north, the Northerner came upon Hickman and the rest of the group on the raft in the middle of the Mississippi River near Jefferson, Missouri. Hickman and the rest of the people on the raft were towed to Lowertown Saint Paul, Minnesota by the Northerner.

Minnesota had suffered a labor shortage in the 1860s because many laborers had gone into the military service during the Civil and Dakota Wars. A lot of jobs had opened up, especially in the agricultural sector. This made farmers seek Black labor, “contrabands,” to work their fields because “hired negro labor is, on the whole, more efficient, because more tractable and more docile, than the class of white labor which is usually available for such purposes,” reported the Saint Paul Press in May of 1863.

When the Northerner approached the levee in Lowertown Saint Paul, Minnesota, a mob at the dock, which was largely composed of Irish laborers, began to verbally and physically assault the newly arrived free Black men and women. The Saint Paul Press reported, “It was impossible for an impartial spectator who witnessed the scenes at the levee on those occasions, not to assign the negro to a higher type of civilization than the white barbarians who howled around them as if, like beasts of prey, they thirsted for their blood.” This dangerous reception prompted the captain of the Northerner to instead direct his steamboat to Fort Snelling located a few miles upriver from Lowertown. U.S. Army officials at Fort Selling took in the Black men and women in efforts to alleviate soldiers' workload and to help with the labor shortage in the state.

Unbeknownst to Hickman and his people, Fort Snelling was the site of the concentration camp for Dakota women, children and elders in 1862 to 1863. As Hickman and his people set foot onto solid land they witnessed the Dakota people “file mournfully past the very site of their sorrow to board the same steamer that had brought Hickman and his group from Missouri to this wretched spot and now would take the Dakota dependent to whatever fate awaited them” (Green 76). Hickman and his people witnessed more forceful removals of the Ho-Chunk and Dakota people via steamboats traveling south on the Mississippi River. Hickman and the rest of the group spent the summer and fall at Fort Snelling, and eventually some, including Hickman, settled into Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Hickman went on to hold services for Black men, women and families calling themselves the “Pilgrims.” In 1866, Hickman led a “baptismal service on the Mississippi River” in Saint Paul and Pilgrim Baptist Church -- the church Hickman had established -- was formally chartered (Wilson). It was not until 1874 that Hickman, because he was a Black man, was legally ordained in the state of Minnesota and remained the congregation’s minister until 1886. Additionally, in 1869 Hickman would be among one of the first Black men to ever serve on a jury in Minnesota. On February 6, 1900, Hickman died a free man, a licensed minister, and a part of Minnesota history.

Kristy Ornelas

AmeriCorps VISTA Servicemember

Mississippi Park Connection

Sources

Adams, Jim. "A Voyage of Remembrance: Pilgrim Baptist Church Members Rode a Riverboat to Fort Snelling, as their Founders did in 1863.” Star Tribune, Oct 10, 2010.

“The Emancipation Proclamation.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, 17 Apr. 2019, www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation.

“The First Negro Jurymen.” The Minneapolis Daily Tribune, March 25, 1869.

Green, William D.. The Children of Lincoln : White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity in Minnesota, 1860-1876, University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Jones, Haru. “The Emancipation Proclamation: The Civil War in Four Minntes.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/videos/emancipation-proclamation.

“Memory Map.” Bdote Memory Map, bdotememorymap.org/memory-map/.

Wilson, Cynthia. “Robert T. Hickman (1831-1900).” BlackPast, March 18, 2008, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hickman-robert-t-1831-1900/.