Last updated: January 6, 2023

Person

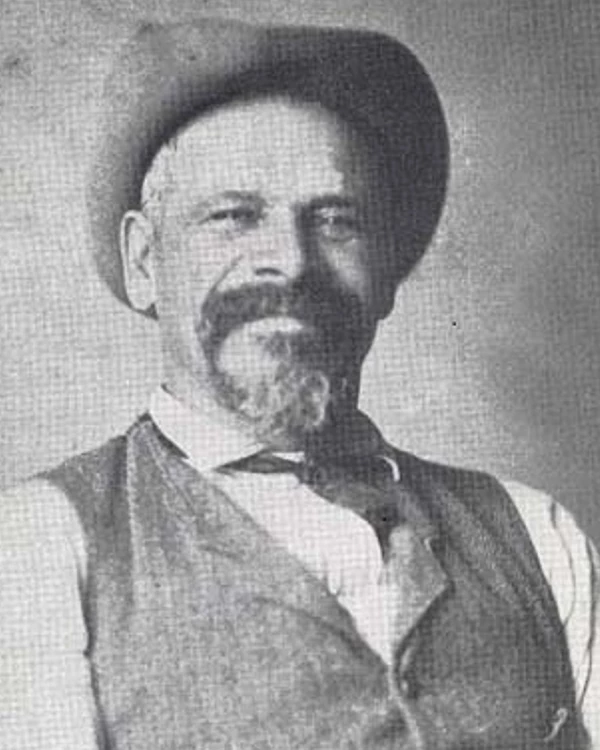

Peter Bruner

A Slave's Adventures Toward Freedom Not a Fiction, but the True Story of a Struggle, 1918

The officers asked me what I wanted there and I told them that I came there to fight rebels and that I wanted a gun…After I had been there about a week they made up a regiment and called it the Twelfth U.S. Heavy Artillery.

Early Life

Peter Bruner was born in 1845 in Winchester, Kentucky, and enslaved by a man named John Bell Bruner. Bruner’s enslaver was an alcoholic and extremely abusive; nearly every day he brutally beat and punished Bruner at the slightest provocation. Bruner made several attempts to escape his enslaver’s cruelty and make his way to a free state, but he was always caught and returned to slavery. After one frustrated escape, Bruner attempted to jump from a building as he “preferred death to slavery” but was prevented by his captors. He repeatedly told John Bell Bruner that he did not care what happened to him, whether he was sent into the Deep South or killed. Bruner asserted, “I would tell him sometimes that I wished he would kill me at once and I would be done suffering in this world.”

Civil War

Peter Bruner self-emancipated by enlisting as a private with the US Army at Camp Nelson in July 1864. He was assigned to the newly created 12th United States Colored Heavy Artillery [USCHA], organized on July 15, 1864. His duties included guarding supply lines and livestock, manning fortifications outside Bowling Green, and patrolling various points along the Ohio River.

The 12th USCHA did not see battle in Kentucky or Tennessee, but Bruner talks of small skirmishes with Confederate sympathizers. Soldiers of the 12th USCHA endured the difficulties of camp life, including deadly outbreaks of disease and exposure to the elements. Bruner recalled that throughout the winter, soldiers slept in tents and would often awaken to their blankets frozen to the ground or covered in snow that blew under the canvas.

The 12th USCHA mustered out of service in April 1866, and Bruner set off for Winchester to see his mother for the first time in eighteen years.

“Slave Narratives”

Bruner is one of a very few Black soldiers and formerly enslaved people who compiled an autobiography of his life and military service. A Slave’s Adventures Toward Freedom, written with help from his daughter, details the terrible conditions of Bruner’s enslavement, repeated attempts to escape slavery, and eventual enlistment and service in the US Army.

Bruner’s autobiography is a rare and important resource from the 19th century. For nearly 250 years, millions of African Americans were enslaved in the United States. Generations of people lived, worked, and died throughout the country with hardly any record of their existence, except perhaps a bill of sale assigning a dollar value to each person. Enslaved people were prohibited from learning to read or write, and as a result, very few first-person accounts of slavery are available to read or study. After his self-emancipation and service in the US Army, Bruner attended school in Ohio and was able to educate his children in the same manner. From these circumstances, he was able to share his life story and experiences where millions of others throughout history could not.

Post-War Life

Bruner eventually settled in Ohio with some relatives after the war and spent some time in school studying reading, writing, and geography. Bruner married Fannie Procton in 1868 and worked for several schools throughout the region, finally taking a position as janitor and caretaker at Miami University. Bruner and his family enjoyed many friends and broad support in his community, and he took pride in his work and the life he built after the war.

Peter Bruner joined one of the largest regiments raised at Camp Nelson, during one of the busiest recruitment periods of USCT soldiers in camp history. His remarkable experiences through extremely cruel treatment, dangerous escape attempts, service in war, and work to build his life as a freedman and citizen were shared by many of his fellow soldiers, but only a fraction of those voices and experiences have been preserved through history.

After spending times in his early life wishing for death as an escape from enslavement, Bruner offered words of encouragement and hope in the opening lines of his book:

In this book I have given the actual experiences of my own life. I thought in putting it in this form it might be of some inspiration to struggling men and women.

In this great, free land of ours, every person, no matter how humble or how great seems the handicap, by industry and saving, can reach a position of independence and be of service to mankind.